What is self-sovereign identity (SSI)?

What is self-sovereign identity?

Self-sovereign identity (SSI) is a set of personal attributes that an individual can control, share with any private party or public institution, and revoke access to at any time at their discretion.

SSI is built on decentralised technical architectures and prioritises security, privacy, individual autonomy and user agency.

What does self-sovereign identity enable?

SSI lets people create a universal, lifelong digital identity and credentials independent of centralised providers. The economic benefits flow from the following unique features of SSI:

- Lower costs of issuing and verifying credentials.

- Standardisation of information — adoption of universal data standards.

- Fraud resistance — cryptographic signatures are hundreds of times more secure than physical signatures.

- Decentralised storage of encrypted data is less vulnerable than giant centralised databases.

- Context unification — the ability at the software level to combine data from different sources for content verification and audit.

- Instant privacy compliance checks — users control access to their data, enabling SSI systems to meet information-protection requirements.

- Personalisation — users can build portfolios of preferences or achievements to receive tailored services.

What problems does SSI solve?

Data fragmentation

The digital world and its web of interactions call for a new class of documents: open and accessible to every user, natively digital, available on a personal computer or phone, persistent, provable and not dependent on a provider.

As an alternative to social networks, banks and government agencies, SSI offers a universal solution that can connect disparate applications and enable data sharing.

Predefined standards ease adoption and reduce the cost of maintenance and development. Unlike traditional models that require hundreds or thousands of APIs, SSI needs only a one-time definition of a document schema, after which any third party can consume it. Although schemas are public, personal data are shared only with the clear permission of their owner.

Another benefit of connecting isolated data stores is the ability to extract value from raw data. A factory worker who always arrives on time can prove punctuality to a future employer. A pupil who has completed thousands of homework assignments can craft a personalised learning strategy by the time they enter university.

Inefficient document handling

The value of any credential lies less in its content than in the services, products and opportunities it unlocks. A degree may be needed to get a job or a research grant; financial records are required to obtain a credit card or open a corporate bank account, and so on.

To make services faster and more convenient, bureaucratic systems must be automated. Algorithms — not people — should verify and accumulate identity data and handle documents. Automation streamlines, modernises, standardises and accelerates processes, and helps address corruption, discrimination and personal bias.

As more bureaucratic systems adopt verifiable credentials and SSI, trust in the process will grow. For example, after a bank completes business reputation checks and KYC, the client can reuse the result to obtain another service from a different organisation, provided that organisation trusts the bank.

Data standardisation

Scaling and further automating existing trust systems requires a standard native to both humans and machines. As more documents are issued and verified by software, the need for standardised, machine-readable data formats rises.

Standardisation also eases integration among different data providers and verifiers. Instead of building pairwise API integrations — an expensive and time-consuming exercise — an entire industry or country can adopt a shared data format backed by verifiable credentials.

Privacy

End-users and regulators are paying increasing attention to data protection. Businesses must comply with rules such as California’s Consumer Privacy Act, the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, America’s Federal Information Security Management Act and many others.

Compliance with the EU’s general data protection regulation will cost Fortune Global 500 companies $7.8bn a year, while compliance with California’s privacy law will cost American business $55bn.

SSI enables the full privacy toolkit: transparent data use, the right to be forgotten, auditability of data use, and regulator permission management via version-control systems.

In the digital age SSI may be a remedy for “surveillance capitalism”. If users control their personal data — choosing with whom to share them and when to revoke access — those data cannot be used for criminal purposes. Internet companies will not be able to monetise users without their unambiguous permission. Moreover, they will be obliged to share profits with users. Online business will shift paradigm: from hoovering up the maximum amount of user data to providing better service.

Where did SSI come from?

According to some researchers, the concept of self-sovereign identity emerged from attempts to apply the Bестфальскую систему международных отношений at the level of the individual. That system arose in Europe from the Peace of Westphalia, which concluded the Thirty Years’ War in 1648. Its core tenets — sovereign statehood, self-determination and direct self-governance — still apply.

The ideological forerunner of SSI was the concept of self-sovereign authority. Its proponents argued that the capacity for independent (sovereign) self-governance is an “innate” human trait, predating the emergence of “registration” processes that enable participation in public life. Registration implies that identity requires a society-controlled administrative process. Society is then cast as the owner of identity and the individual as a product of socio-economic administration.

Achieving digital sovereignty — the ability of individuals to act and decide knowingly and independently, and to control their data, devices, software, computing resources and other technologies — hinges on managing identity data.

Often the term “self-sovereign identity” is used interchangeably with “decentralised identity” and “digital identity”.

Digital identity, expressed and stored digitally, has evolved alongside the internet. Domain names, email addresses and social-media accounts are all forms of digital identity essential to daily life.

How does the SSI architecture work?

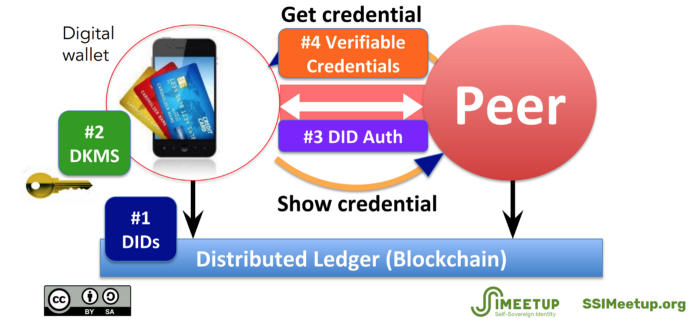

Digital identity consists of three elements: a decentralised identifier (DID), an authentication system, and a certification system based on verifiable credentials (Verifiable Credentials).

In addition, SSI includes DKMS — a decentralised key management system. It manages private keys via digital signatures.

Decentralised identifier (DID)

A DID is a machine-readable identifier for any person, organisation or thing. It allows holders to prove control over a digital identity and to issue or receive verifiable credentials.

A user can maintain multiple identifiers (for business, government, close friends). Identifiers are typically free, easy to generate and under the user’s control.

Verifiable credentials (Verifiable Credential)

Verifiable credentials are documents and claims issued by one DID issuer and sent to another party (the holder). Issuer and holder can be the same entity, though usually they are not. Depending on the use-case, verifiable credentials may be a simple data fragment (confirmation of an email address, phone number or physical address) or a relatively complex structure such as a bank statement.

The four SSI elements form a layered stack:

- the first layer anchors identity;

- the second interacts with the base distributed ledger and stores user data and private keys;

- the third uses second-layer data to authenticate the user’s identity.

After successful authentication, the Verifiable Credentials layer can exchange various credentials to prove the user’s identity. Layer interactions resemble the TCP/IP suite: each layer has its own protocols and specifications.

Which SSI organisations exist?

Because SSI demands close coordination across protocol suites, progress depends on unified specifications and well-designed protocols. Non-profit organisations provide them, including:

- Rebooting Web of Trust (RWoT);

- W3C Credential Community Group (W3C CCG);

These organisations have worked productively over the past five years. The most active is RWoT. Since 2016 it has published 56 white papers, as well as many technical specifications and open-source codebases.

RWoT specifications have been submitted to the W3C and IETF for further standardisation. The DID draft specification is largely based on RWoT’s work (even the term SSI originated at RWoT).

Which specifications does SSI use?

1. Decentralised identifier (DID)

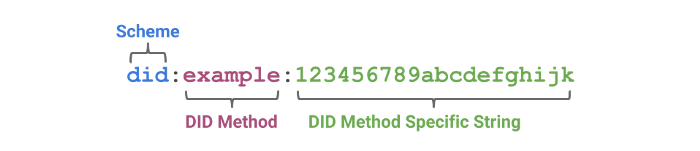

The DID is the lowest — and most critical — layer in the SSI architecture. It handles writing and reading identities in a distributed ledger. A DID, consisting of letters and numbers, is unique and bound to a DID document in a specific distributed ledger.

A DID comprises the following:

- DID methods — identifiers used to resolve each DID. Every ledger has a specific DID method and rules for creating/transferring a document. For example, a DID registered in Ethereum might look like did:eth:12345. For a resolver to recognise a DID method, it must be registered with the W3C.

- DID document. A distributed ledger can be viewed as a key–value store. The DID is the key, and the DID document recorded on the ledger is the value. The DID document contains the public key representing the identity, the authentication method, service endpoints capable of interacting with that identity, and so on.

- DID resolution mechanism. This helps higher-level protocols dereference a DID document. The resolver can analyse different DID methods and return the result upstream. Upper-layer protocols need not know the details of document parsing.

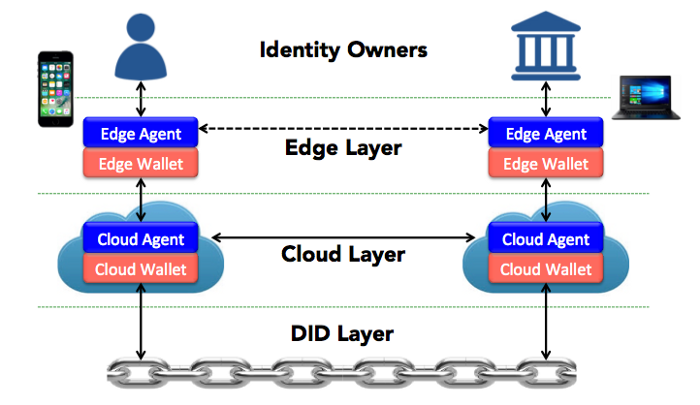

2. Decentralised key management system (DKMS)

DKMS is the main interface for using SSI. In addition to linking to an underlying DID, it should provide storage for credentials, private-key backups, and more.

From a specifications standpoint, DKMS can be divided into three sublayers:

- DID layer — handles interactions with the underlying distributed ledger to perform DID lookups.

- Cloud layer — stores personal data for consumption by upper-layer protocols

- Edge layer — manages private keys.

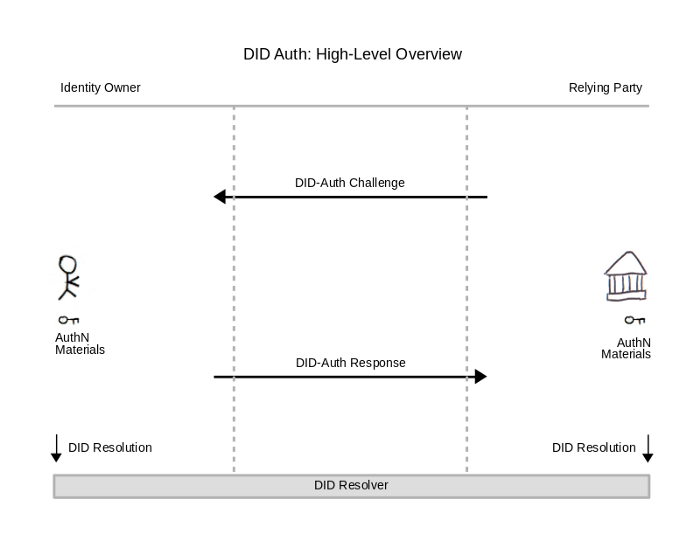

3. DID authentication

There is not yet a single, unified DID authentication standard, although RWoT has published many papers exploring standardisation.

The DID authentication system serves one purpose: it lets a user prove possession of an identity. The user need only prove control of the private keys corresponding to the SSI public keys. Once authentication is complete, a communication channel can be established through which individuals exchange verifiable credentials and other resources.

Various authentication protocols exist — OAuth, OpenID and others. Similarly, DID authentication uses a challenge–response model: the verifier issues a challenge, the ID holder responds, and the verifier confirms the response’s authenticity.

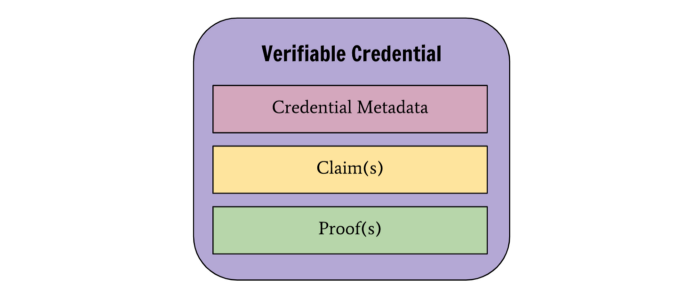

4. Verifiable Credential (VC)

VCs are the earliest and most mature specification in the SSI stack. As a high-level SSI protocol, they have a single purpose: to replace all the credentials in a user’s wallet.

A VC is a cryptographically protected digital certificate that can be used across applications. With VCs, identity becomes a coherent whole under the holder’s full control, who can present selected credentials depending on the use-case.

A VC has three parts:

- A subject claim describing the subject–property–content relationship. For example, “Alice — pupil — school” describes Alice as a school student.

- Certificate metadata with additional information such as type, issuer and issuance time.

- Proof: a digital signature attesting to the issuer’s content.

How is SSI evolving?

In recent years the SSI ecosystem has advanced rapidly, with new applications, protocols and specifications.

Government agencies, corporations and universities have launched products and pilots: the US Department of Homeland Security, the European Commission, Europass, the World Bank, the World Economic Forum, MIT, Harvard University, UC Berkeley, the UK’s National Health Service, Singapore’s Immigration and Checkpoints Authority, IBM, Microsoft, SAP, Oracle, and the governments of Finland, Canada, South Korea and many others.

In March 2021 Microsoft launched ION, a decentralised identity solution on the Bitcoin blockchain with open-source code. The technology lets users prove their identity to access certain information. If an account is deleted, access to linked services is preserved. As with signing transactions on Bitcoin, a DID serves as proof of control. ION nodes monitor identifiers and anchor timestamps to the blockchain.

In April 2021 the company behind the Cardano cryptocurrency, IOG (formerly IOHK), and Ethiopia’s government agreed to deploy the Atala PRISM decentralised identity system. The solution will be rolled out across 3,500 Ethiopian schools to protect access to academic records for 5m students. IOG believes Cardano and Atala PRISM will “democratise social and financial services for 1.7bn Africans”.

Cooperation with IOG will kick off implementation of the government’s “Digital Ethiopia 2025” strategy, under which a national identity standard has been introduced. Atala PRISM became the first credential-issuing system based on it.

The number of consumer-facing applications remains smaller than one might expect for a technology with potential reach in the billions.

What obstacles stand in the way of SSI adoption?

The road to mass adoption of SSI features several hurdles:

- Digital wallets and auxiliary services lack flexible integration to let users recover credentials and data if lost.

- Existing data-protection rules are not directly applicable to SSI. Lawyers, notaries and regulators often have only a vague grasp of the technology, slowing the creation of legal frameworks.

- An underdeveloped wallet ecosystem to connect users to decentralised SSI infrastructure.

- Mass adoption requires intuitive, user-friendly solutions from both private firms and public bodies.

- No fully fledged market of SSI-compatible applications.

- Governments are slow to encourage a transition to SSI: they do not issue SSI-compatible national IDs, or build the necessary technical frameworks and legal bases.

- Key recovery today is not independent, fast or effective enough.

- Because SSI relies on an immutable, decentralised ledger that stores cryptographic proofs, privacy can suffer if not only proofs but data themselves are recorded on public ledgers. Decentralised ledgers and blockchains should not store documents and confidential information as traditional databases do, but only proofs of such data.

- Using public, decentralised and immutable ledgers requires significant effort to ensure pseudonymity of data and identifiers. Personally identifiable data should not be placed in public ledgers.

- DID and VC standards must keep evolving and be adopted and recommended by SDOs such as IEEE, ISO, ITU and NIST.

- Appropriate regulation is needed for electronic signatures, transactions and digital certificates.

- The right to be forgotten must be respected. Under Article 17 of the EU GDPR, in certain circumstances “the data subject shall have the right to obtain from the controller the erasure of personal data concerning him or her”.

- Scaling SSI solutions requires efficient decentralised ledgers. Today’s ecosystem of unregulated, non-interoperable ledgers and blockchains is far from ideal. Attempts to build public regional networks — EBSI in Europe and LACChain in Latin America — have been relatively successful.

- Trust frameworks: national and private frameworks should be developed to set assurance levels for e-services. Qualified identity providers should be certified — for example, under the EU’s eIDAS.

- Biometrics holds great promise for identity proofing and authentication, but remains underused.

Why traditional business models fail in SSI:

- Data cannot be sold. In SSI, a user’s verifiable data, documents and personal information do not belong to the platform — nor even to issuers and verifiers. A verifier must obtain permission for any data operations, which is impossible without the user’s consent — contrary to SSI principles.

- Online advertising sales depend mainly on the quantity and quality of user data held by platforms. The profits of Google, Facebook and Twitter reflect the accuracy of user profiles and the efficacy of targeting algorithms. SSI adoption would break that linkage.

- Although many SSI applications generate data that could underpin markets (for example, labour markets where employers seek candidates with diploma credentials), in practice third-party use requires the data owner’s consent.

- Because the industry is nascent, SSI companies should not charge users for actions such as creating DIDs, signing digital certificates, and so on. Otherwise, both demand for and supply of data will fall, slowing adoption.

- Not every SSI interaction should incur a fee. Ideally, providers distinguish which operations and transactions deliver user value and charge commissions only on those.

Follow ForkLog on Twitter!

Рассылки ForkLog: держите руку на пульсе биткоин-индустрии!