Anonymity is simply not on the agenda: Sergei Shashev on what the launch of a state digital currency will change

One of the hottest topics of 2022 was CBDCs: many countries drew near to issuing a state digital currency that is meant to change our understanding of money.

News about CBDC projects in various countries appears almost every week. Yet details on how exactly they will work and how they will affect the economy often remain under wraps.

In the crypto community, digital currencies are more likely to be viewed with suspicion, calling them almost an «pure evil». At the same time, some experts consider CBDCs the foundation of the monetary system of the future.

On what CBDCs are really needed, how their issuance will affect the crypto market, and what they will change for business and ordinary people, ForkLog spoke with Sergei Shashev — founder of Broxus and one of the leaders of the blockchain community Everscale, on the basis of which several national digital currency projects are already being implemented.

Why governments want digital currencies and how they will affect the economy

ForkLog (FL): Is CBDC adoption inevitable for the global monetary system? If yes, how long might this process take?

Sergei Shashev (S.S.): The inevitability is a philosophical question; I view it through the lens of trends. Since the start of this year geopolitical conditions have shifted sharply, a military conflict has begun, and the number of countries allowing a pilot CBDC project has doubled. As has the number of countries conducting research in this direction.

There is a dedicated service, according to which two‑thirds of countries have a CBDC on their agenda. Pilot projects are under way in 47 countries, and 4 countries are already implementing CBDCs. Fifteen countries are close to this, five of which we are in talks with regarding participation.

FL: What are the fundamental advantages of CBDCs over the current monetary system?

S.S.: The introduction of a digital currency enables automation of many economic processes at the state level. For example, tax payments, contributions to pension funds. Right now this is handled by a huge bureaucratic apparatus, plus corruption inevitably arises in the distribution of financial flows.

Addressing this problem alone would contribute substantially to GDP growth. A study in China found that over a ten‑year horizon, issuing a digital yuan would raise growth rates by 50%. That is, if the usual GDP growth is 4-5% per year, with CBDC adoption it would be 7-8%. And that is a compound growth, meaning the effect of the digital currency would build over time.

As early as next year, in my view, at least one or two countries will begin trading with each other through digital currencies. And others will inevitably feel a compelling urge to join this process. Especially those that trade with China. China today dominates the global economy and is present in many regions. This is the “Great Chinese Financial Silk Road,” but in all countries at once.

FL: You mentioned war as a factor accelerating CBDC development. How are these connected?

S.S.: All governments have seen that if a military conflict or some other event occurs, your funds can be frozen, especially those denominated in dollars. Therefore, for example, Gulf states — I’m not talking about Iran, but Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia — have begun paying much more attention to a state digital currency.

FL: If CBDC technology spreads, will digital currencies completely displace existing settlement methods — cash and bank accounts? Or will they coexist?

S.S.: First, CBDC adoption will be a long process. If you look at history, bank cards appeared only a few decades ago, and banking apps less than ten years ago. And only now are they being adopted en masse.

Moreover, different countries move at different speeds. In Sweden, cash has almost disappeared. In IKEA stores they even proposed banning cash payments, but ultimately decided it would infringe migrants’ rights and kept it. In China almost all domestic payments go through WeChat.

In Europe, generally, if you have more than €10,000 in cash, the state immediately asks where it came from and why you need so much. Because most payments are conducted via cards and digital accounts. On the other hand, in the United States, despite digitisation and the spread of cryptocurrencies, paper checks are still in use.

So all these methods will remain, but digital currency will gradually become dominant.

FL: Today there are two main types of CBDC under development: retail, which is a full analogue of money, and wholesale, which is intended only for interbank settlements in external trade operations. Which of these types is more popular?

S.S.: It depends a lot on the level of infrastructure in a country. There are Southeast Asian countries with high smartphone penetration and mobile financial apps, and many residents do not have access to bank accounts. Most there view a wallet in a service like Gojek or Grab as a bank account and do not know what SWIFT, SEPA, correspondent accounts, etc. are. For such users, CBDC integration would be highly seamless.

There are countries where mobile payments and all that comes with it are not widespread, and CBDC adoption will spread much more slowly, likely starting with external trade. This could be very poor countries like Venezuela, which need to trade resources, or developed countries in Europe where fintech is hampered by strict regulation.

In general, legislation is a critical factor. In many developed countries changes come slowly because there is a complex social contract that takes into account the interests of various stakeholders, and lawmaking is therefore sluggish.

In countries with a simpler social contract or even authoritarian states, the implementation of a national digital currency will be much faster. Take, for example, the Nigeria case and the “electronic naira”, where for this purpose a ban on cash withdrawals above $200 has been introduced. The acceleration of CBDC adoption is taking place in the United Arab Emirates and, likely, in Myanmar and Vietnam.

Can anonymity be preserved for CBDC payments?

FL: One of CBDC’s main criticisms is the privacy threat. It is claimed that if authorities have access to the digital currency’s code, they will be able to track virtually any transaction and any address. This is especially relevant for undemocratic countries. How warranted is this risk?

S.S.: Let us consider it from another angle. A fully trackable CBDC, like in China, is a scenario Orwell could not have imagined. You would have a complete trace of all spending by every household. That is how it works. CBDC is not about privacy in the sense of “completely.”

But if you think Bitcoin and stablecoins are about privacy, that is not the case. Approximately 90% of addresses and transfers, if not more, have long since been decoded, and even in DeFi cybercrime investigations proceed quickly. Because the ledgers are promixed, and if you move cryptocurrency through mixers or try to hide its movement, your address automatically ends up in the “gray zone.” All crypto is gradually marked as “white” and “gray,” and in the “gray” there are already “shades of black” that no one should touch.

So even standard crypto is divided into several “worlds.” Take Ethereum and Tron as an example. A couple of years ago there were many “strange” operations in Ethereum, including hackers and money laundering; now this has largely moved to Tron. There are not many cross‑chain bridges for this network to move large volumes of crypto. In other words, it is a form of segregation.

As for traceability in CBDC — you simply cannot escape it. In banks it is already nearly universal, and you can only dodge control with cash. But then comes the question: if you are a law‑abiding user, what difference does it make to you? And if you seek anonymity, then something is wrong with you. We can see things differently, but that is the societal consensus, or at least most people think this way.

FL: It seems to be a paradox: CBDC technology is actively discussed in crypto communities, while cryptocurrencies were created with anonymity in mind. And state digital currency is the anti‑thesis of that concept.

S.S.: Yes, a yin and yang. But I am convinced it will all mix: there will be both CBDCs and cryptocurrencies. And these worlds will be connected in some way. In crypto terms it is a boon, as the overall size of the “cryptoworld” grows, just differently.

FL: One more quick question on privacy. From public sources about existing CBDC projects, in many countries they still embed the possibility of anonymising transactions. Can you confirm?

S.S.: Let me say this: nowhere we have negotiated was privacy a cornerstone. It will arise either at later stages of implementation or during testing. For now the main questions are: what legal frameworks should exist, how the link with banks should work, how to transition from fiat stablecoins to CBDC, how to conduct cross‑border trade, how to integrate into “super apps,” how to obtain regulatory approvals. Anonymity simply is not on the agenda.

Which countries will be first to issue CBDC

FL: In several countries CBDC pilots are already under way. The brightest example is, of course, China. Progress is also visible in Nigeria, Sweden, and Caribbean nations. How successful are these pilots, does practice differ from theory, and what key lessons have their organisers drawn?

S.S.: Of the cases mentioned, I cannot go into detail about Sweden. It is important to note that Nigeria and the Caribbean projects were handled by the same group of developers, and I have been in contact with them.

In the Caribbean, they released the digital currency early, a few years ago. And coverage figures were very weak. There was no problem with the legislative framework, but they “hit a wall” on infrastructure.

For CBDC to work, you need smartphones, virtual cards, QR codes for payments, established business processes, and so on. All this is underdeveloped in the region. Therefore the rollout stalled and stopped; digital currency services in the Caribbean currently operate very sluggishly.

As for Nigeria, there is an established financial infrastructure, but another problem is high inflation. People have little motivation to hold the naira and not exchange it quickly for Bitcoin or dollars, because money loses value quickly. So CBDC is being addressed with coercive measures, notably restricting cash withdrawals.

One more important note: to change infrastructure in any country you must invest some money. And if you are a large country, there is a scale effect. Suppose you spent a few hundred million dollars to build CBDC infrastructure, and the costs are recouped quickly. If it is a small country with under a million people, payback is low. And this is another reason the Caribbean effort failed.

I think Nigeria’s process will proceed normally, because the state can start implementing various mechanisms, for example social payments via CBDC. And then the population will join.

In China, everything is as successful as possible. There, I think, 267 million people already use the digital yuan, of whom 40-50 million have lived in this new monetary system for more than a year. That is, they have proven that CBDC works, and now the next phase is cross‑border trade using the digital yuan. This is a colossal milestone, and I am sure it will happen as early as next year.

Using digital currency in cross‑border transfers and everyday life

FL: How realistic are expectations that retail users will be able to conduct fast cross‑border payments without correspondent banks? And could you list the clear advantages of digital currency over the existing digital money system?

S.S.: Cross‑border payments in CBDC are the core task we are pursuing now. To answer your question, let us consider my favourite operational example we are working on — the Philippines and the UAE.

In the UAE there are about 400,000 Filipino expatriates, and they regularly send money back home. In the Philippines, an income of about $100 a month is considered normal. So a person earning $1,000 a month in the Emirates can support their family back home.

The same monthly pattern occurs. The worker in the UAE needs to send money. This happens in two ways: first — the old hawala system. The person goes to the leader of the local community, gives him dollars, and the counterparty in the Philippines provides the recipient with the same amount in pesos. It happens outside banks, and by this method a large amount of money is sent, perhaps 30-40% of all cross‑border transfers. The same thing happens in routes like “Russia‑Uzbekistan” or “Malaysia‑Bangladesh.” The system works when there is a large Muslim community.

Second method: sending money via money‑transfer systems like Western Union. The fee “on the round” depends on exchange rates and ranges from 6% to 12%. You inevitably incur double conversion. The overall transfer cost is high. It is no surprise that in Vietnam, for example, fees can be near zero, but that is a special case.

What we are trying to build. The sender comes with digital dirhams or to a money‑transfer point, or to a dedicated terminal. He needs to convert dirhams into pesos. Both currencies are represented digitally as stablecoins in an AMM pool, where the exchange rate moves very little. The exchange happens directly from dirham to peso, without conversion into dollars. There is liquidity on both sides of the pool. At the other end, pesos are received via a remittance operator, which charges only 0.1% for exchanging the digital currency. Thus total fees do not exceed 3% of the transfer amount.

This is one way to use digital currency. It is convenient and cheap for those who have neither cards nor bank accounts. And this is several hundred million people in Southeast Asia alone.

If you live in Europe and have cards and SEPA accounts, CBDC for transfers is not needed at all. In Europe the driver for digital currency could be processes such as pensions and social benefits.

FL: And beyond payments, what other everyday uses are there?

S.S.: Probably the ability to set up programmable actions. After all, CBDCs can support smart contracts. Starting with the banal — automatic birthday fund collection, sending funds to a deposit or a fund for a child’s education. Of course, some banks have such features, but with CBDC programming actions is generally very easy thanks to smart contracts.

FL: In one of the podcasts you suggested that one criterion for the programmability of digital currency could be legal norms.

S.S.: Yes. For example, children using CBDC could theoretically be prevented from purchasing prohibited goods, such as alcohol or tobacco.

How CBDCs will change business and international trade

FL: Let us move from retail users to enterprises. It is said that for business one of the key aspects of CBDC is the potential to improve settlement in external trade operations. Could you explain in more detail what the exact gains are?

S.S.: It is essential to understand that today any foreign trade transaction goes through the dollar. There is, for example, Pakistan and the United Arab Emirates. Between them there is large trade turnover. It all goes through dollars. This places constant pressure on national currencies, because you must constantly sell rupees and buy dollars. At the same time, the dirham in Pakistan is trusted. That is, direct settlements in dirhams and rupees are possible, and this can be arranged with CBDC.

The second reason is that there is a risk of freezing dollar accounts. If you look at how SWIFT has worked over the last ten years, you can see its gradual degradation. In current banking realities there are many staff in the KYC and AML areas, and this activity requires ongoing costs. It also slows transfers. New transaction processing rules keep arising, which all banks somehow must follow.

As a result, trade problems arise even among neighbouring countries. There is demand to “straighten” cross‑border transfers. This could include currency baskets, AMM pools, and mutual correspondent banks. There are different architectures. In one way or another, for almost all countries this will simplify and reduce the cost of economic processes as cross‑rates and long chains of intermediaries disappear.

Finally, the paperwork for trade operations decreases. This segment is Trade Finance. Suppose goods are shipped from China to a Malaysian port and then imported into Indonesia. In this process there is the hiring of ships, cargo insurance, letters of credit, delivery rules, force majeure, and so on.

In each such operation several banks participate. At different stages you must obtain various confirmations: that the cargo is not counterfeit, that the cargo was shipped, accepted, and so on. It is a huge process with many participants and intermediaries. Fraud is inevitable.

This process can be built in the crypto world — with smart contracts, token locking, and multi‑signature wallets. And such changes in Trade Finance will come in three or four years. Because it is more complex than simply moving cross‑border operations to CBDC.

FL: If we draw a conclusion, then CBDC could shorten the chain of intermediaries and simplify trust-related processes in international trade.

S.S.: Yes, that’s right.

Comparison of CBDC projects in China, the United States and Europe

FL: You have mentioned China many times. But there are at least two other players — the United States and the European Union. How far have they progressed in creating a digital dollar and euro?

S.S.: In the United States there are several projects, three of them led by MIT. The core protocol is OpenCBDC, and its development also includes the Fed. It is likely to win.

As for Europe, the situation there, in my view, is weaker and at the same time more decentralised. Many EU members are pursuing their own initiatives. I don’t think they will manage to agree on launching a single project, because the EU has become very bureaucratic, and they will take a long time to decide.

FL: Many view CBDC as a threat to cryptocurrencies. In China, for instance, operations with cryptocurrencies were banned, and not just once on more than one occasion. If a state digital currency becomes a reality, how will roles between it and crypto assets be distributed?

S.S.: There is no direct link between banning crypto trading in China and issuing CBDC. They can peacefully coexist, as in Nigeria. There is no contradiction.

What is important to understand: most CBDC projects will start with stablecoins pegged to national currencies. In this architecture’s “trick,” you can create a stablecoin and, gradually updating the smart contract, expand the user base and experience, convert it into a CBDC, handing control of the asset to the central bank.

When the movement initially comes from the central bank, it gets bogged down in “sandboxes” and bureaucracy, so the process moves very slowly. If you start with stablecoins, that will be advantageous for the crypto market.

Its market capitalisation has already grown disproportionately thanks to stablecoins and could grow even more. Imagine you have a stable crypto asset for rupees, dirhams, dong, pesos, and so on. That expands the overall crypto market. In addition, millions of new users appear.

Features and benefits of issuing CBDC for a blockchain platform: the Everscale case

FL: Turn to Everscale. You say active work on CBDC is one of the ecosystem’s important priorities during the “crypto winter.” Please detail what benefits such projects bring to your blockchain, its participants, and holders of the native EVER token.

S.S.: No matter how the Everscale protocol evolves, its forks and individual components, a CBDC project is a substantial increase in R&D budgets, a recognition of the technology and its dissemination.

It turns out that any stablecoin that can become a CBDC, in conjunction with wallets in the Everscale network integrated with other ecosystem applications, leads to a growth in the number of users. And that is an ideal environment for the development of virtually any decentralised applications.

As for EVER holders, the picture is somewhat more complex. One way or another, demand for EVER will grow through the same fees.

FL: Earlier representatives of the project, including you, publicly confirmed that a CBDC technical platform is already being developed on Everscale in several Middle Eastern and Southeast Asian countries, with a number of states in talks. What is the status of these projects? Can you share new details?

S.S.: Let me start from the beginning. Our first participation was in a tender in Georgia. There I saw who needs CBDC and for what. Then we ran a pilot with EUPi — now called EverCash — which is developing a euro‑pegged stablecoin. So far the project has not gained wide adoption, but they have found their niche.

From this I understood the advantage of Everscale for CBDC. Any wallet in our network is a smart contract. This means you can build a mult-sig system for the central bank and banks, and these flows can be separated: users own the assets, while wallets and rules over them belong to banks. In other words, you can progress toward CBDC via stablecoins, gradually introducing new rules and terms into the smart contract, without inconveniencing the user.

We began talking about this and gradually reached the United Arab Emirates, where we chose our technology. Note that this is not the native Everscale platform, but a separate blockchain. The UAE has already adopted a good regulatory framework, and the country has strong banks. Everything is moving very intensively and developing. We will share more details when possible.

We also have two projects in Southeast Asia — the Philippines and Indonesia, where we are working with local partners to create stablecoins for remittances. We recently signed a memorandum of understanding with a company in Cambodia, with Vietnam in the queue. In Indonesia we have already reached the integration stage. We are currently addressing the strategy to move a rupiah‑based stablecoin into CBDC.

FL: Everscale is an open protocol. How could it become the foundation for a CBDC that implies a closed system?

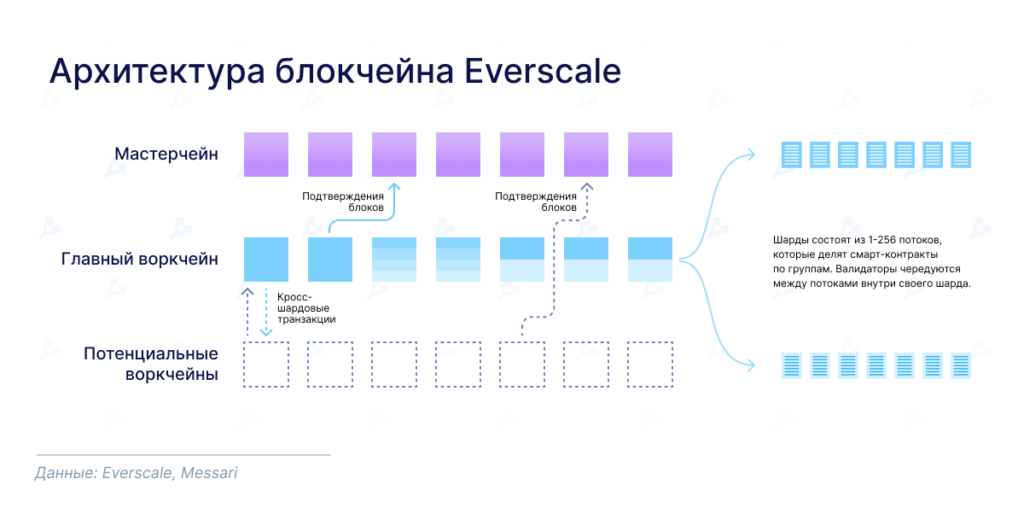

S.S.: The architecture of Everscale includes workchains. It is a blockchain that operates under its own rules, with its own set of validators, and fees in its own token. We are currently finalising this technology.

How this should work: the CBDC operator creates its own workchain and has full control inside it, including issuance and fees. The workchain operator can even pay the “gas” for users or set its own commissions. This resolves all tensions. But such a system will work only if there is a large anchor player.

FL: As I understand, every Everscale workchain ultimately connects to a masterchain that is responsible for the overall consensus.

S.S.: Yes. But at the same time there is no direct link between using EVER for gas and the workchain. The main advantage of Everscale for CBDC development is that every address is a smart contract. There are virtually no other blockchains like that. In second place are custom fees.

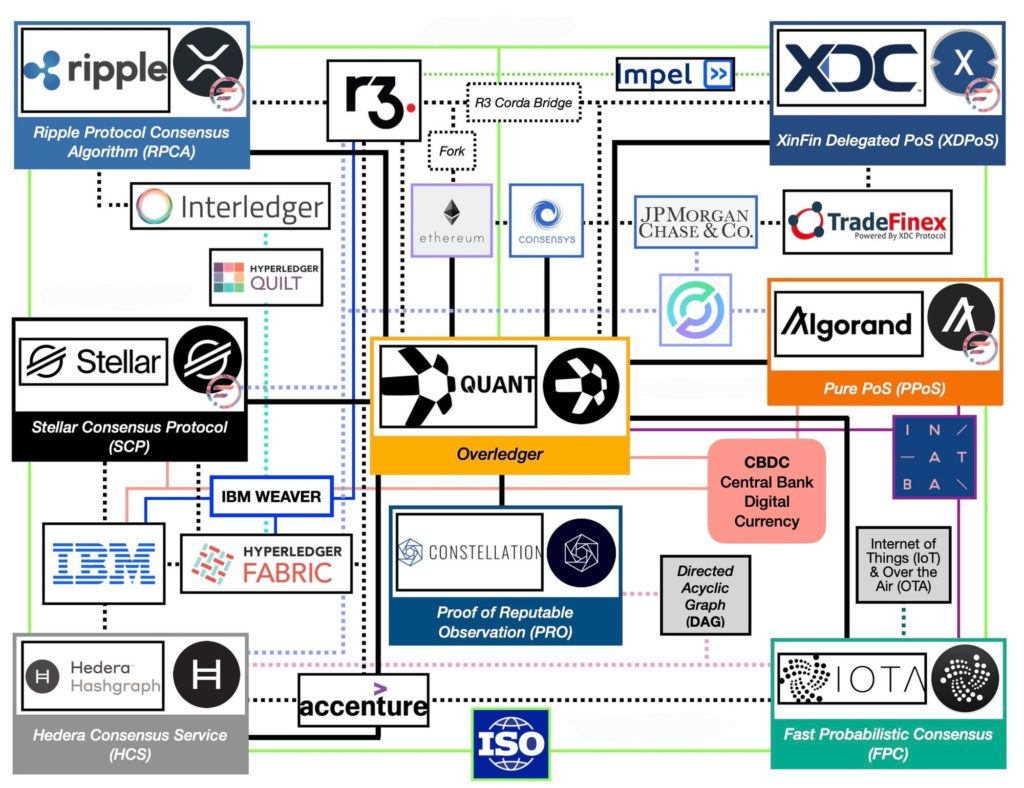

FL: And finally, on which blockchain platforms might we still see CBDC projects?

S.S.: Many started building national digital currencies on Hyperledger. But this is being dropped because IBM stopped supporting the project. And it is not a particularly suitable technology.

Some are building CBDC, say, on Ethereum with Proof‑of‑Stake. I have also heard about Corda. Naturally, Binance and BNB Chain have become major players in this space — they currently have a pilot project in Kazakhstan. Changpeng Zhao personally travels to various countries and tries to persuade authorities to adopt their ecosystem. There is also the Zetrix blockchain, which are implementing a project for Malaysia and China.

In any case, I think now everyone will try to get involved in this topic. For Everscale the good news is that we began working on CBDC over a year ago and already hold strong positions in many countries.

Read ForkLog’s bitcoin news in our Telegram — cryptocurrency news, rates and analysis.

Рассылки ForkLog: держите руку на пульсе биткоин-индустрии!