From Blood Diamonds to AI Metals: Africa’s Unending Resource Wars

AI’s arms race is fuelled by Africa’s wars—and the minerals they feed on.

Africa, often described as the cradle of civilisation, has for centuries been trapped in near-constant armed conflict. The continent most richly endowed by nature is in the grip of a “resource curse”.

It is now clear that in the tales of “blood” diamonds the only fiction is the gallant adventurers. Today gemstones are used to pay rebels, and the struggle for rare-earth metals—needed by corporations to develop artificial intelligence—is masked as ethnic conflict.

How did we get here?

1960 entered history as the “Year of Africa”—17 countries then gained sovereignty, freeing themselves from the sway of France, England, Italy and Belgium. More states later proclaimed independence.

At the time these events were seen as a fresh chapter: citizens hoped for better lives and politicians for global recognition and diplomatic rights.

But history took a harsher turn. After decolonisation a flywheel of civil wars began to spin, and it has yet to stop.

In the 1960s conflicts engulfed Algeria, Tunisia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Uganda and many others. Some fought for independence from Europe; others for power at home.

The cold war added fuel to Africa’s bonfire of “civic self‑awareness”. The two superpowers—the US and the USSR—pursued mirror-image interests, scarcely hesitating to bankroll opposing factions in plain sight.

Angola became one of the hottest fronts. The Soviet Union sought influence over the country’s leadership; America strove to thwart it. The classic clash of hegemons produced a 27-year civil war that claimed more than 500,000 lives.

Today Angola is one of the largest oil producers and, thanks to diamond mining, has one of the fastest-growing economies. Yet about half its people live below the poverty line.

Angola’s conflict is a vivid, if hardly unique, example of how rivalry between great powers can escalate and ensnare other countries, to the detriment of vulnerable states and peoples. Sadly, current governments seem to have learned little.

The resource curse

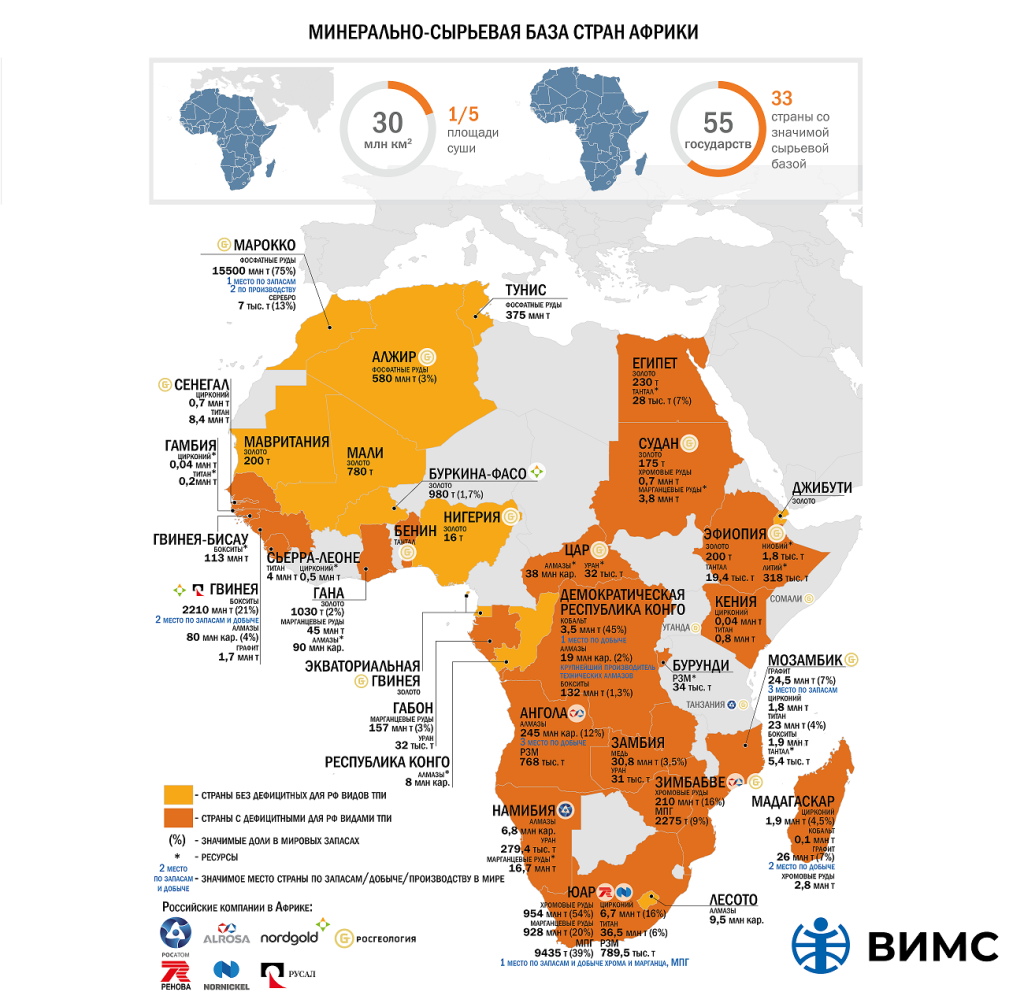

Many scholars call Africa a “geological marvel”. By various estimates, the continent holds up to 30% of the world’s raw materials, including oil, gas and mineral ores.

According to VIMS, Africa’s subsoil contains 86% of the world’s chromium ores, 71% of platinum-group metals, 69% of diamonds, 57% of phosphates, 44% of bauxites, 43% of cobalt, 41% of graphite, 27% of tantalum, 23% of manganese ores and 22% of uranium.

Attention is now particularly fixed on rare-earth elements (REEs), of which Africa also has plenty.

They comprise a group of 17 metals with similar chemical properties. In recent years REEs have found wide application, from electronics to mechanical engineering.

The problem with rare earths is not their “rarity” but the difficulty of extraction. They are often recovered as by-products of other deposits, such as gold—complicating purification. “Direct” access to REEs is therefore prized.

China is the de facto monopolist here, accounting for 69% of rare-earth production. That reality is pushing other powers to act more actively—and more radically—especially in long-suffering Africa.

Apocalypse now

If cold-war conflicts were ideological, today they are overtly about resources. The old colonial powers never left, persisting with an “economy of plunder”.

DRC

For the Democratic Republic of the Congo, war has become a permanent business model. For three decades now, the continent’s deadliest conflict has dragged on, claiming, by various estimates, more than 6m lives.

Formally it is an ethnic struggle between Tutsis and Hutus. In reality it is a battle to control cobalt mines—vital to the manufacture of electronics, smartphones and cars.

The rise of AI has further stoked demand. Cobalt is essential for high‑energy batteries and the chips used to train artificial intelligence.

The M23 rebel group, backed by Rwanda, is a textbook modern “resource” army.

Fighters seize deposits, impose their own “taxes” and sell ore through convoluted chains of intermediaries to international corporations. The weapons and cash received in payment then fund more war—a vicious circle paved with “blood cobalt”.

In the summer of 2025 US President Donald Trump moved to reconcile the DRC and Rwanda by proposing a deal. He added that China “has already bought up many minerals in the republic, so the United States has to catch up”.

According to the US State Department, Congo’s mineral reserves are valued at $25trn. As part of a peace accord, the DRC and Rwanda agreed to launch a “security coordination mechanism”, ensuring a share of resources for the Americans.

But M23 did not show up to sign. The group accepted the restoration of “state authority” nationwide, yet vowed not to surrender “an inch” of its territory.

CAR

In the Central African Republic the “resource curse” has evolved from local chaos into a criminal vertical of power.

The region runs on “force in exchange for a licence”. According to an AllEyesOnWagner investigation, Russian entities (first the “Wagner” PMC, now the “African Corps”) offered the government a bundle of services: guarding the president, training the army, fighting rebels.

Payment is not in money, which the CAR lacks, but in exclusive subsoil rights. It is hardly 19th‑century colonialism; rather, an outsourcing of sovereignty—delegating the right to coerce and to control resources to foreigners.

What are the benefits of such a “business model”? “Blood diamonds” no longer need to be smuggled through the jungle. They are mined by a company with a French name and a Dubai registration, shielded by a government licence and foreign mercenaries.

The set‑up suits almost everyone involved: local elites take a cut to preserve the appearance of power; outsiders get effectively laundered resources. Ordinary citizens, as ever, are left with a bloody strongman and poverty.

Sudan and Libya

These two countries show what happens when the “resource curse” reaches its terminal stage: state collapse and the monetisation of chaos.

In Sudan, where civil war reignited in 2023, rival generals Abdel Fattah al‑Burhan and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo are competing not for the capital but for logistics. Whoever controls the road from the gold‑producing Darfur region to the Red Sea port controls the money flows.

Their war is not a political quarrel but a contest between two criminal syndicates for an export channel.

Libya is often called a filling station for mercenaries. After the overthrow of Muammar Qaddafi, it became an ideal hub for non‑state groups.

Arms from the dead dictator’s arsenals are traded freely, mercenaries are recruited and smuggling proceeds are laundered. Libya is an archipelago of anarchy, where war funds—and reproduces—itself.

Blockchain will not help here

The bipolar world of the 20th century has given way to a multipolar scrum. In the DRC the interests of the US (via support for Rwanda), China (via loans and infrastructure) and Russia (via armed groups) already collide. This “war by proxy” is even less predictable, with no end in sight.

Many well‑meaning actors have tried to blunt the harm, for instance by making money‑laundering harder. Some even proposed blockchain. A distributed ledger can indeed trace a gemstone from mine to buyer. But it is powerless against a machete: transparency technology shatters against the reality of pervasive violence.

African resources are a potent temptation. Every great power that comes for them ends up not in control but as yet another prisoner of the “resource curse”, compounding the continent’s tragedy.

Рассылки ForkLog: держите руку на пульсе биткоин-индустрии!