Crypto-fascism in Action: How Central-Bank Digital Currencies Could Shape Economic Freedoms

In Chuck Palahniuk’s novel “Adjustment Day” (Adjustment Day), the concept of money with an expiry date was explored. One of the characters wrote in his book:

«That’s why it is so important for money to have an expiry date. Power passed from generation to generation in abstract wealth leads to inequality and corruption. You cannot save money for the sake of saving. Money must constantly work for the good of society».

Palahniuk’s novel appeared in 2018, and within a few years governments had a tool capable of turning that idea into reality.

We are talking about CBDC, whose programmable functions will allow central banks not only to manage monetary policy effectively but also to exercise control and censorship of transactions, as well as mass surveillance.

Researchers CEPR believe that one of the main risks of introducing national digital currencies is the concentration of power in the hands of monetary regulators. For this reason it is hard to understand why even democratic countries study such a possibility.

- Tech companies and banks have long been collecting user data — this kind of surveillance is nothing new. Monetary regulators are also interested in this information because they use it to manage monetary policy.

- CBDC will not only enhance the ability of central banks to collect data, but will also allow them to directly influence consumer spending patterns. Moreover, thanks to programmable capabilities, digital currencies can become a real weapon.

- Experts believe that China — one of the leaders in the CBDC race — may use programmable money in tandem with a social credit system to strengthen the power of the Chinese Communist Party. If successful, other authoritarian regimes may adopt this approach.

New Oil

If Bitcoin is called digital gold, data can rightly be considered digital oil. Back in 2006 British mathematician Clive Humby said:

«Data is the new oil. Like oil, it is valuable, but not in itself, but because of the products built from it. Data must be processed and analysed to extract value and improve business profitability».

Therefore there is nothing surprising in the fact that tech companies actively collect information about their users. To understand the scale of what is happening, one only needs to recall the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

In 2018 it emerged that the British analytics company collected user data via its Facebook app. The incident affected about 50 million users — the information pulled from their profiles was used to target political advertising, including during the US presidential race when Donald Trump won.

Cambridge Analytica denied guilt to the end, but eventually lost almost all its clients and had to file for bankruptcy. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg acknowledged a mistake, though prior to that he spent five hours answering questions before the US Congress on two occasions.

Regulators in the US took note of the company’s missteps and opened investigations. To settle a dispute with the regulator, the corporation paid a $5 billion fine.

Subsequently Congress summoned the owners and executives of US tech giants to the regulator’s scrutiny, and EU regulators expressed concern about their growing influence and began drafting bills to curb them.

In my mind no doubt that platforms — and the algorithms they use — can have an enormous impact on the way we see the world around us. We need to know why we are shown what we are shown.https://t.co/5FHSXQlPBQ

— Margrethe Vestager (@vestager) October 30, 2020

Tech giants, meanwhile, unveiled a number of initiatives. For example, Apple forced developers to clearly show what user data their products collect.

Together with that, the company planned to introduce a feature that scans users’ iPhone photos for child abuse. After a flood of negative feedback, Apple postponed implementation of the mechanism for an indefinite period, but did not abandon it entirely.

According to Security.org, corporations continue to aggregate user data on a massive scale. For example, Google collects not only obvious information like IP addresses or browser history, but also more personal data, such as the content of emails, geolocation, and payment details.

Such companies claim that they work with anonymised data, but the public questions the veracity of these statements. Especially when there are precedents for using this information in law enforcement investigations.

According to court documents obtained by Forbes reporters, US authorities secretly ordered Google to monitor and provide data on users’ search queries by keywords.

“Keyword warrants” is a thing for Google, apparently. This was X-Files conspiracy theory stuff a decade ago. https://t.co/UbDU6Ec08D

— Matthew Green (@matthew_d_green) October 8, 2021

The report noted that law-enforcement agencies requested information about suspects involved in human trafficking and violence against minors.

The company analysed traffic, identifying users who entered relevant queries. The list of data provided included IP addresses and collected cookies. This data enables identifying an individual.

Players in fintech, and their traditional rivals — banks — are not much different from Big Tech in this respect. Except that their ability to surveil, especially regarding payment data, is greater.

If Google and Apple see only transactions made using Google Pay and Apple Pay, and operations linked to their services, then credit institutions have access to the full spectrum of financial information.

Your bank knows almost everything about your spending patterns, where you live, what you do for a living and which store you prefer for groceries on Mondays. It is well aware of your financial position and health. It knows what devices you use, and in some cases even has biometric data.

All this information opens up broad possibilities for analysis, including behavioural analysis.

But consumer data is of interest not only to the private sector but to the state as well. And central banks are among the first in line for such data.

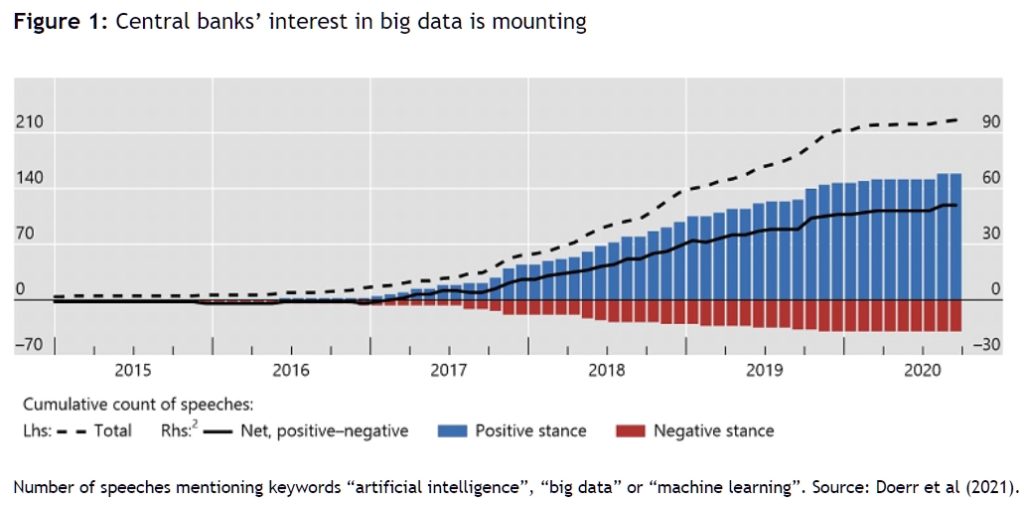

Economists SUERF noted that most monetary regulators (~80%) use big data to achieve goals of monetary policy and financial stability, as well as analytics and strategy development.

Experts say central banks’ interest in this area is only growing, and the main obstacles are IT infrastructure shortcomings and data leakage to commercial entities.

Regulators request information from private-sector players or develop their own technological platforms. Both approaches yield results, but evidently the latter is preferred.

For example, Chinese authorities have required local fintech companies to provide data on clients and borrowed funds to state credit agencies. Ant Group has already agreed to comply with this requirement.

The Bank of Russia has even monopolised biometric data collection, and the Faster Payments System, through which the volume of transactions has already tripled, allows regulators to gather information about citizens’ transactions.

And if private banks and tech companies see this data as essential to profitability, central banks have even more ambitious plans.

While this form of money offers undeniable advantages, CBDCs could become a tool for suppressing freedom. Regulators will gain the ability to influence spending directly and access vast data stores.

The Human Rights Foundation’s chief strategist Alex Gladstein wrote:

«Elimination of cash and the ability to instantly analyse financial transactions will enable surveillance, state control and, ultimately, social engineering on a scale never before imagined».

Dominic Frisby, author of Bitcoin: The Future of Money? (Bitcoin: The Future of Money?) shares a similar view. He notes that the programmable features of CBDC are its main drawback.

According to Frisby, while fiat money implies a certain freedom, digital money fully eliminates it. Governments will also gain direct access to users’ wallets, which will allow easy taxation or fines — all that will require is to change a couple of lines of code.

«The all-seeing government will see every transaction», — the writer wrote.

In his view, programmable money features can be used against individuals or as weapons in economic warfare. Integration with social credit systems will widen the punitive or rewarding capabilities.

One can reasonably observe that payments are subject to a strong network effect, and CBDC transactions are no exception. Perhaps no one will ban people from continuing to use banknotes or traditional electronic money, but the reality is that with a more advanced tool it will inevitably win a substantial market share from older forms.

The trend toward cash replacement is already evident in many countries. According to the Bank of Russia, cashless payments in Russia have reached 75%. In Switzerland, banknotes are used only by 43% of citizens, though in 2017 the figure stood around 70%.

Many presume that physical money will not vanish due to the so-called paradox of cash. Yet this phenomenon is more about crisis-driven consumer withdrawals from banks and hoarding of savings at home — there is little real circulation of banknotes.

Another telling example is Bitcoin’s legalisation in El Salvador. The population was not familiar with cryptocurrencies, and there were many questions about the authorities’ actions, but this did not prevent the Chivo wallet from quickly gaining popularity.

President Nayib Bukele said in September that the app is actively used by 2.1 million residents. Skeptics estimate the real figure is far lower — around 784,000. Yet given that the law recognising Bitcoin as legal tender took effect only on 7 September 2021, the result remains striking.

The dollar is king in El Salvador. A survey by Fusades found that 87.9% of Salvadorans have not used #Bitcoin in transactions. Yet, @nayibbukele says Salvadorans love Bitcoin, and of course, the fearless authoritarian Bukele.

— Steve Hanke (@steve_hanke) October 11, 2021

Electronic money currently in use are records in databases of commercial banks and payment systems. Their value rests on one simple fact: these bits of information can be exchanged for banknotes that central banks issue. CBDCs will take on this function, rendering the above instruments obsolete.

To avoid the collapse of the traditional banking system, regulators will almost certainly impose certain restrictions. For example, the Bank of Russia will not pay interest on balances in wallets holding digital rubles. This will allow credit institutions to retain part of their income from deposits.

Nevertheless, players in the financial sector foresaw the digitisation of money and are already transforming their businesses to meet the future realities. Payment systems could become a linking hub between CBDCs of different countries, while banks act as intermediaries in distributing the digital currency.

Paying for conveniences with economic freedom. That is why former NSA and CIA officer Edward Snowden considers the instrument “the latest danger hanging over society.”

«CBDC is something close to a perversion of cryptocurrencies, or at least their fundamental principles and protocols. Crypto-fascist money, a malevolent double, clearly designed to deprive users of property rights in their money and make the state the middleman in every transaction», — he wrote.

Red — The Season’s Hit

Among developed nations, China leads the CBDC race. Here the instrument is in the final stage of pilot testing — broad public access is expected in February.

Over the past year China has steadily prepared the ground for the launch of e-CNY. Authorities have crafted the regulatory framework and upgraded the infrastructure.

Some experts also regard as part of this broad campaign the outright ban on cryptocurrencies, mining and activities of organisations dealing with digital assets.

China’s successes in CBDC development offer a glimpse of how digital money integration could affect economies and societies in other countries.

The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) began researching the digital currency as early as 2014. For a long time the project drew little attention, but after Facebook’s Libra announcement in 2019 the regulator said that a prototype of e-CNY was nearly ready for launch.

In July 2021 the PBoC published a technical document devoted to the digital yuan. It became clear that the instrument is compatible with existing payment systems, is accessible even to residents of foreign jurisdictions, and is ready for use in cross-border settlements.

The PBoC also confirmed for the first time that its CBDC supports smart contracts and is programmable.

Earlier trials in the Sichuan capital showed that use-cases for the e-CNY could be limited. In the tests residents were given digital money that could be spent only on transportation via the city’s Tianfutong and Meituan apps.

The PBoC document does not specify whether the digital yuan will be integrated with China’s SoCS, but experts do not rule out such a possibility.

In the CNAS, the Center for a New American Security, they suggest that the CCP uses the e-CNY in tandem with SoCS to consolidate and strengthen its power.

«This technological leap is an important step in expanding digital authoritarianism of the party. […] In addition to information about users and transactions, the CPC will obtain various metadata related to movements of people and devices. The PBoC will become the owner of a substantial data set that could be merged with tools of censorship and surveillance of people», the experts write.

In MERICS, the social credit system is described as “part of Xi Jinping’s data-driven governance vision.” Analysts believe the CCP pursues a clear aim — to broaden analysis of information from existing sources to consolidate and strengthen power.

Where does #China’s Social Credit System stand today? Our new MERICS China Monitor takes a deep dive and introduces the general framework and key mechanisms that have been established to guide the system into the next phase. Read it at https://t.co/RcPBKwqJxw

— MERICS (@merics_eu) March 4, 2021

Despite the name, SoCS is fairly fragmented and is more of a foundation with which several initiatives, including the digital yuan, could be integrated.

In forming this “system of systems” 47 state agencies are involved under the leadership of the PBoC. The latter’s direct involvement is another argument in favour of the reality of this linkage.

The social credit system is geared toward compliance with existing laws, but state authorities can abuse such power. When Beijing introduced mandatory Mandarin-language education in Inner Mongolia schools, parents who removed their children from these schools were threatened with being placed on a blacklist.

China also operates a facial-recognition system that can locate a person in seven minutes. All of these components together expand the government’s repressive capabilities. And if successful, other authoritarian regimes may imitate Beijing’s approach.

Sound Money

In 2009 Satoshi Nakamoto, the creator of Bitcoin, wrote that the main problem with fiat currencies is that they require trust in the issuer — central banks. And the latter have repeatedly shown that trusting them is not warranted.

“The root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that’s required to make it work. The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust.”

— Satoshi Nakamoto

— Bitcoin (@Bitcoin) March 29, 2020

In the book The Theory of Money and Credit, Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises notes that sound money belongs to the same category as the Bill of Rights.

«It is impossible to understand the meaning of the concept of sound money unless one realises that it was designed as a tool to protect citizens’ liberties from despotic incursions by governments».

In turn, CBDC is a tool of monetary control — it does not solve the fiat problem, but exacerbates it.

In today’s reality, the adoption of national digital currencies across countries is a matter of when, not if. Like fiat money, their strength will depend on the power and influence of the central banks behind the issue.

Experiments in weaker economies are unlikely to significantly shift the global financial system. Yet the experience of leading nations, if successful, will be emulated by others—even those nominally democratic.

In a world where CBDCs are a priority means of settlement, including cross-border, there will be little room for private life. After all, a tool marketed as a means to boost financial inclusion could end up being a noose around economic freedom.

Read ForkLog’s Bitcoin news in our Telegram — news on cryptocurrencies, prices and analysis.

Рассылки ForkLog: держите руку на пульсе биткоин-индустрии!