How Wirecard collapsed: dubious clients, forged reports and a €2bn hole

The card-issuing Wirecard, one of the 30 largest German companies by market capitalization, went bankrupt at the end of June, turning out to be a carefully masked hollow shell.

It turned out that the company processed enormous cash flows from illegal online casinos, bookmakers and porn sites, and year after year presented growing financial figures in its reports.

The company’s partners are now being required to pay fines, declare bankruptcy and explain themselves in court. Proceedings around Wirecard threaten to eclipse the initial phase of the 2021 German parliamentary elections. eclipse.

Early stage

Wirecard founded by programmers Detlev Hoppenrath and Peter Herold in 1999 as a unit of Munich-based InfoGenie AG, which traded on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange.

Wirecard developed processing for online card payments, but after the dot-com bubble burst in the early 2000s it found itself on the brink of bankruptcy.

In 2002 Wirecard was led by former KPMG consultant Markus Braun, who undertook its recapitalisation. The company merged with the local competitor Electronic Business Systems, and in 2005 acquired InfoGenie, taking its place on the stock exchange.

The main clients during this period were owners of high-risk businesses: casinos, binary options, gambling and porn sites, FT reports.

After acquiring XCOM Bank in 2006, Wirecard obtained Visa and Mastercard accreditation and the ability to issue payment cards for third-party services. Clients included the British Curve service, the ANNA Money startup (founded by the founders of “Points”), the fintech startup Revolut and Payoneer.

In 2007, Wirecard opened a large unit in Singapore.

As FT notes, even at this stage the combination of banking and non-banking activities made it difficult to compare Wirecard’s financial statements with peers and forced investors to rely on adjusted accounts.

In 2008 a group of shareholders raised concerns about the company’s financial reporting. The British auditing firm Ernst & Young (EY), invited to audit, did not find violations and began working with Wirecard on a continuing basis.

Rapid growth

With the arrival of the new Chief Operating Officer Jan Marsalek in 2010, the company began international expansion. In the following years it aggressively bought Asian payment services and opened offices in New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, Turkey and India.

In 2015 FT published a series of articles, which reported a €250m hole in the company’s balance sheet. In response Wirecard sent letters from lawyers to the editors and hired a large London PR firm.

That same year appeared a report by research firm J Capital Research, which stated that the real volume of Wirecard’s operations in Asia was far smaller than claimed. The German company called the article commissioned and blamed short-sellers who allegedly sought to profit from a fall in its shares.

This defensive tactic was successfully exploited in the years that followed. In 2016, the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin) targeted Zatarra Research, which released a 101-page report with evidence of Wirecard’s involvement in money laundering by offshore poker sites and their transfer to the United States, where online gambling is banned.

Zatarra Research Wirecard by ForkLog on Scribd

EY questioned EY? EY stated that a large amount of Wirecard cash lay on accounts beyond the company’s control.

Around the same time, Wirecard’s accusers and investigative journalists began receiving phishing emails. The campaign lasted for several years. The organizer of the attack remains unidentified.

In 2015, Wirecard’s clients included Russian and Ukrainian online casinos and bookmakers, including 1XBet, Fonbet, Liga stavok, Marathon and others. Money transfers were conducted through several acquiring banks across Russia, circumventing tight regulation of the industry. Also, according to Bellingcat, Jan Marsalek developed ties with Russian intelligence.

In 2017, Wirecard acquired a subsidiary of American Citigroup that sold prepaid bank cards.

In the same year the company reported 33,000 large corporate customers and another 170,000 small services. But FT journalists who accessed internal reports found that more than half of Wirecard’s revenue came from just 100 customers.

Among them were online bank Monzo, the Hungarian low-cost carrier Wizz Air, the Russian-rooted bookmaker Marathonbet, brokers of binary options and forex trading banned in several countries such as Rodeler and Hoch Capital. Part of the revenue came from porn sites, which paid high processing fees.

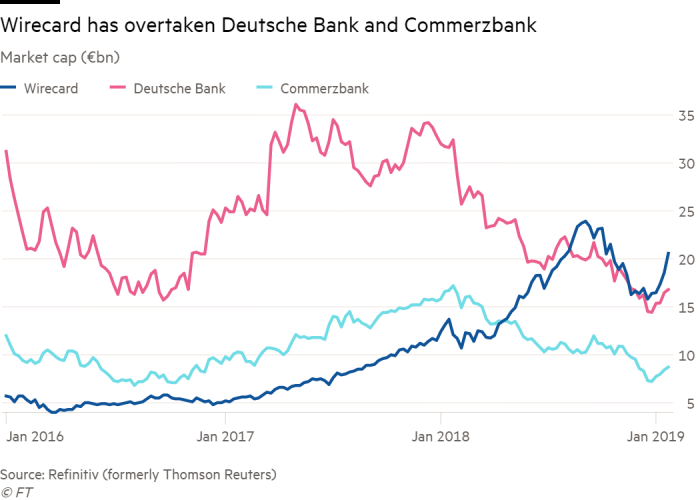

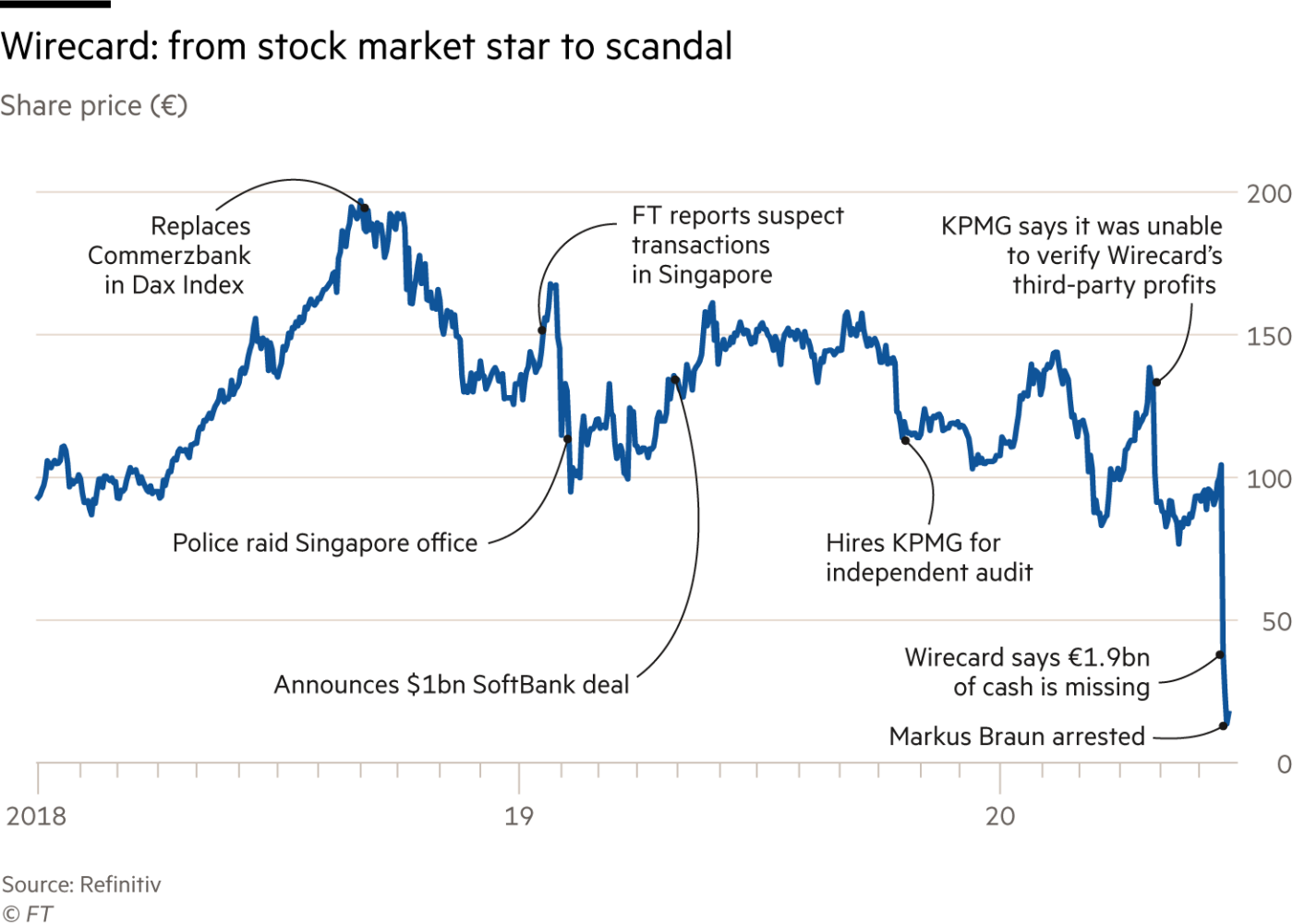

However, another clean audit by EY fuelled investor enthusiasm — Wirecard’s shares rose more than twofold to a market cap of €24bn. The company overtook Deutsche Bank and Commerzbank, and in September 2018 replaced the latter in the DAX 30 index.

The inevitable end

The next major investigation focused on Wirecard’s Singapore office. In March 2018, employees at the Singapore branch suspected their colleagues of concluding fictitious and backdated contracts and falsifying accounting.

Based on this information, in early 2019 FT published an article proving that the local subsidiary overstated revenue and fabricated deals with Asian counterparties, shifting large sums between divisions in Germany, China and India.

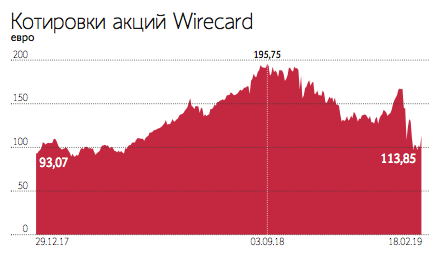

As a result of the official investigation, the Singaporean prosecutor charged five Wirecard employees and eight of its Asian subsidiaries with fraud. The stock fell roughly 40% from January 30 to February 15, 2019.

The German regulator then banned short-selling by Wirecard shares for two months due to the risk of further declines and opened an investigation into journalists from FT, suspecting market manipulation.

The other Wirecard units repeatedly passed EY audits for 2018 without issue.

In March 2019 FT reported that Wirecard had outsourced half of its business, and payments for it were processed by partners – one such company registered at the home address of an elderly seaman in the Philippines.

In April, Wirecard received €900m in funding from the Japanese conglomerate SoftBank. At the same time FT wrote about three dubious partners of Wirecard in the Philippines, Singapore and Dubai, on whom much of the company’s earnings rested. BaFin again sided with Wirecard, filing a complaint against journalists.

In an October 2019 article FT published documents showing that Wirecard overstated sales of subsidiaries in Dubai and Dublin, attributing clients that did not exist to them.

Shortly thereafter FT found evidence that funds from partner trusts were being deposited into Wirecard’s financial statements.

Under investor pressure, Wirecard brought in auditors from KPMG to conduct a review. But after six months, in April 2020, they reported that they could not verify €1bn on the company’s accounts or confirm deals from 2016–2018 that had generated the bulk of its revenue.

The German EY unit also faced difficulties auditing 2019 and delayed publication of results several times. Wirecard CEO Markus Braun told investors the delay was due to the coronavirus pandemic and rejected any wrongdoing on his part.

In early June the regulator filed a complaint over potentially misleading statements made by Wirecard prior to the KPMG report. The Munich prosecutor opened criminal proceedings against Braun and three other members of the company’s management. Wirecard offices were searched.

On 18 June EY said it could not corroborate the trust manager’s claim of €1.9bn on two Philippine accounts, representing about a quarter of Wirecard’s total balance sheet.

Concurrently, the board said it had found evidence that the manager had attempted to mislead the auditor, and that those funds probably never existed.

The Philippine central bank confirmed that both banks did not cooperate with Wirecard.

EY’s audit subsequently uncovered “clear signs of sophisticated fraud involving multiple parties across the world in various entities.”

Braun resigned. Before leaving, he hinted that the company itself might have fallen victim to a large-scale fraud.

At the same time, Marsalek, the chief operating officer, left the company. After his disappearance he moved a large amount in Bitcoin and is believed to have fled to Russia.

A temporary CEO with full executive authority was appointed in James Frye.

Soon after, Munich police arrested Braun on suspicion of falsifying evidence of cash balances on the company’s accounts.

According to investigators, the fintech firm was robbed before its collapse. It allegedly extended unsecured credits to partners in Dubai, Singapore and the Philippines totaling around $1bn. Wirecard contends these were advances to merchants processing card transactions through Asian partners.

On 25 June new management filed for bankruptcy. Within a week the company’s share price had fallen 99%, from €104 to €2.

According to FT, at the start of June EY prepared a positive conclusion for Wirecard, in which they rejected suspicions of Wirecard’s involvement in financial irregularities.

“Based on the results of the audit, the attached annual financial statements are in all material respects in accordance with German commercial law applicable to corporations, and provide a true and fair view of the net assets and financial position of the company,” the conclusion states.

The draft EY opinion contained no qualifiers for a positive view. Nevertheless, informed sources told FT that such a verdict by EY was made possible by transferring €440m in four installments from a Philippines-based deposit account, allegedly controlled by an Asian trust on behalf of Wirecard, to the group’s accounts in Germany.

Other documents reviewed by FT show that EY insisted on such asset growth in May after the KPMG report was published.

Conclusion

The Wirecard scandal has triggered a cascade of consequences for the company’s partners.

The SdK, a German shareholder association, has filed suit against two current and one former EY auditor. Japanese SoftBank has said it planned to sue as well.

The German watchdog APAS began a full расследование” target=”_blank” rel=”noopener noreferrer”>investigation into EY. If violations are found, penalties and disciplinary actions, including licence revocation, await the firm.

Second-quarter losses in 2020 were borne by three of Europe’s largest banks: Commerzbank and ING each lost about €175m, and Credit Agricole €110m.

Other major creditors of Wirecard include ABN Amro and Landesbank Baden-Wuerttemberg. Each could lose around €180m. Potential losses for Barclays, DZ Bank and Lloyds are estimated at €330m in total.

One of Wirecard’s key partners, the owner of the Philippine payment system PayEasy Solutions, died” target=”_blank” rel=”noopener noreferrer”>died a month after investigators opened a case against him.

Senior Mastercard executive is suspected of involvement in Wirecard’s transactions at the Tanzanian bank FBME. Private investigators are looking into the matter; they suspect the executive hid suspicious, high-risk transactions from Visa and Mastercard.

Finance Minister Olaf Scholz called for stronger financial safeguards for the country and the creation of a European equivalent to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). He also urged faster auditor rotation compared with the current 10-year cycle.

Pressure grew, prompting Angela Merkel’s office to present a timetable for engagement with Wirecard. The chancellery’s aides said they had maintained regular contact with the company.

Merkel supported Wirecard’s bid for a Chinese licence during a state visit in September 2019. Her office was informed of investigations alleging market manipulation shortly before the trip, but denied that it had known of possible “serious violations” at the time.

The shadow also fell on the German regulator BaFin. BaFin chief Felix Hüffeld must answer why, despite substantial evidence of misconduct, it had neglected to scrutinise Wirecard’s activities.

Hüffeld argues BaFin’s remit covered only the banking arm of the group and that it should be held to account alongside the European Central Bank (ECB).

The burden of Wirecard will, in any case, weigh heavy on European regulators. The collapse promises to reform German financial supervision and reshape political dynamics ahead of the 2021 election.

Subscribe to ForkLog news on Telegram: ForkLog Feed — the full news stream, ForkLog — the most important news and polls.

Рассылки ForkLog: держите руку на пульсе биткоин-индустрии!