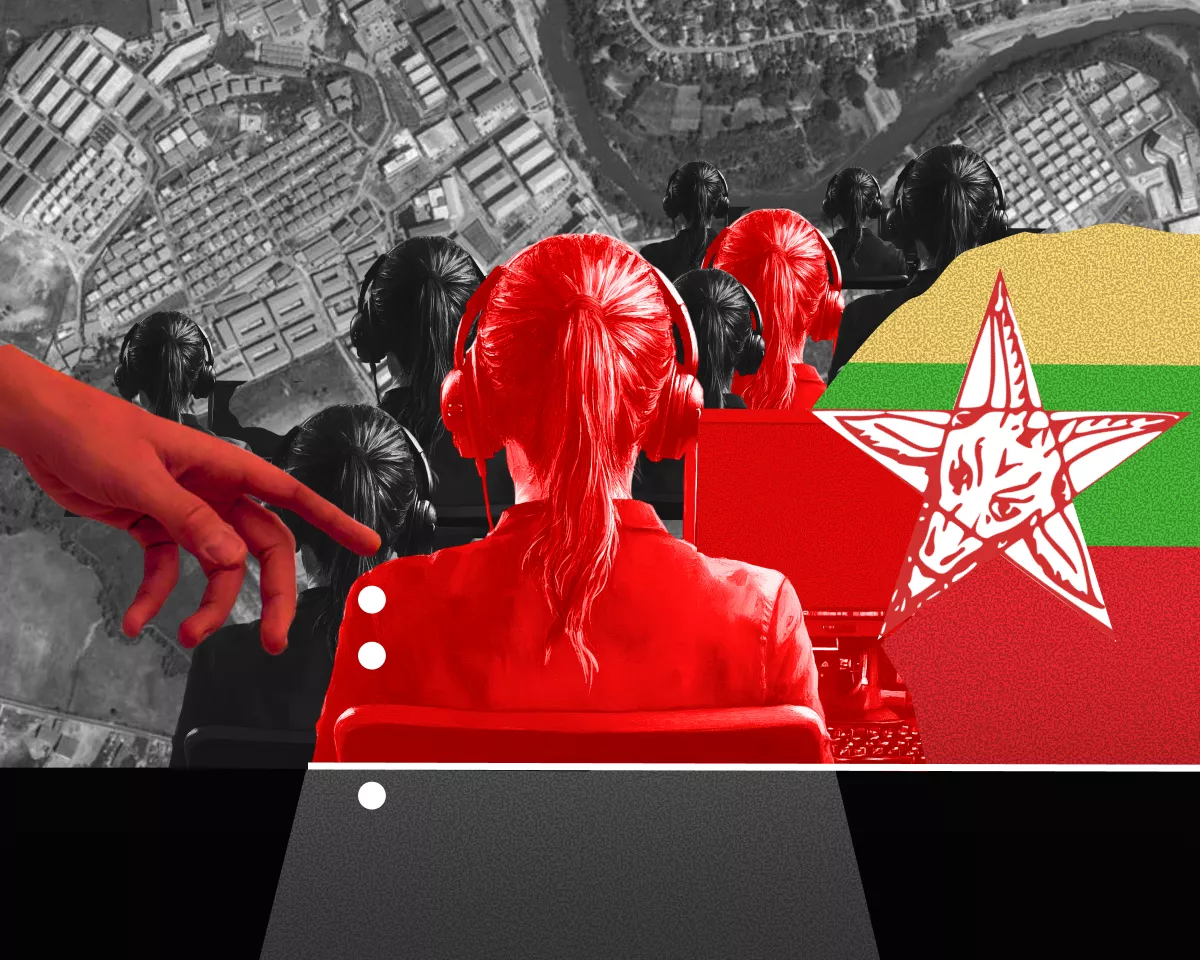

Wracked by civil war, Myanmar has become one of the world’s biggest hubs of cybercrime. In recent years, hundreds of thousands of foreigners, lured by ads for well-paid jobs, have been abducted and forced to work in scam call centres.

These scam compounds are mushrooming along the Thai border and generate tens of billions of dollars a year for their operators.

ForkLog examines why the schemes thrive, whether they can be curbed, who runs them—and where cryptocurrencies fit in.

Historical backdrop

Myanmar (Burma until 1989) gained independence from Britain in 1948. The country immediately plunged into a long civil war between the official government, the communist opposition and allied ethnic armed groups.

A democratisation drive enshrined in the 2008 constitution allowed the first free elections in 2015. Dissident and Nobel peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi took power.

She was ousted in 2021 after yet another military coup. That sparked mass protests, the suppression of which set off a new phase of the civil war, which continues.

The State Administration Council currently rules Myanmar. Its chairman and de facto leader, albeit with limited powers, is Min Aung Hlaing. Alongside the official authorities, various ethnic armed groups control parts of the country.

Great-power competition also shapes the map. In 2013 China’s leader Xi Jinping announced the vast “One Belt, One Road” investment programme to integrate the Chinese economy globally. Myanmar became a target state. Alongside infrastructure building, however, opportunities for shadow business opened in the impoverished country.

In Karen State near the Thai border, new towns sprang up within a few years, meant to be gambling hubs for customers from China. Gambling is banned in mainland China and in most of South-East Asia, but in a war zone in Myanmar no one is watching. In reality, casinos serve as cover for a range of criminal activity.

The scale of crime

Transnational organised crime in South-East Asia is now expanding faster than ever.

In Myanmar, the absence of central control and protection from ethnic armed groups created fertile ground for the drug trade. According to a report by the UNODC, as of December 2024 Myanmar was the leading producer of opium and heroin.

Cybercrime, money laundering, underground banking and human trafficking have also reached industrial scale.

Along the Thai–Myanmar border sit roughly 60 compounds hosting scam call centres. Construction of the first and, to date, largest scam factory—KK Park—ran from 2019 to 2020.

In late 2020 and early 2021, abducted citizens from various countries began to be shipped into the compounds and forced to work the scams.

The factories constantly expand, with fresh buildings going up at each site. If about 120,000 people lived there in 2023, the figure now stands at 150,000–200,000.

How people are enslaved

Foreigners are lured via social networks by job offers for Thai companies in IT, logistics, hospitality, education, digital marketing or online sales.

Listings typically offer scant detail on duties and conditions. Salaries are inflated relative to market rates; online checks will often make the firm look legitimate.

Large scam firms may even stage several interviews—with HR, a direct manager and a regional head—and run an English test.

The candidate’s ticket to Bangkok is paid; sometimes a visa is arranged or its cost is reimbursed upon arrival.

From the airport the foreigner is taken to Mae Sot, a town in northwest Thailand. This is where the crossing into Myanmar takes place, over the Moei river. The scam compounds are visible from the bank; antennas around their perimeter jam GPS signals.

Once there, disoriented recruits have their passports and phones confiscated and are handed scam playbooks. The most common are “pig butchering” and its subvariant, romance scams. The task is to build trust with targets and persuade them to invest in bogus crypto projects. In their work, coerced scammers use generative AI tools and identity data bought on the dark web.

According to UNODC estimates, pig-butchering schemes in South-East Asia now generate more revenue than the drug trade. KK Park alone brings in tens of millions of dollars a month.

Analytics firm Chainalysis in September 2024 recorded a shift by criminals from Ponzi schemes to pig butchering. In the United States, $4.4bn of the $5.6bn in total crypto-scam losses in 2023 came from this type of fraud. Investigators linked the largest wallet associated with pig-butchering operations to the KK Park compound.

Cryptocurrencies are the main payment and transfer rail. Some workers specialise in the memecoin industry: they run branded X accounts and manage bot farms. Low barriers to launch and the option to rug-pull at will make “funny coins” an ideal criminal racket.

Other cyber-offences include property and e‑commerce fraud, and hacks of financial services and other lucrative targets.

Targets are often in Western countries, forcing night shifts of 17–18 hours. Each worker has a profit quota: one former employee was set $5,000 a week, another $10,000 a month.

Failure to meet targets or refusal to work brings physical punishment, up to torture and solitary confinement in a dark room without food. Particularly defiant captives are resold to other scam outfits.

Most centres do not accept ransom; others quote sums that vary: KK Park—$1,500–3,000; Apollo—$4,000–6,000. Even payment does not guarantee freedom.

Rights groups say each factory has a managing director, most often ethnic Chinese, though some centres are co-owned with Thais. Each compound rents out space to 30–40 companies with their own hierarchies: bosses, supervisors, team leads and smaller subordinate teams—anywhere from 50 to 250 people.

Victims include people from South-East Asia (China, Taiwan, Indonesia and others) and Africa (mainly Kenya and Nigeria). Cases involving citizens of Western and, more rarely, post-Soviet countries are rising.

According to UNODC, the scam compounds in Myanmar collectively yield about $40bn in profit a year.

Who is behind it

Several sources claim that Chinese crime bosses who back gambling zones on the Myanmar–Thailand border run the network.

According to the BBC, one likely beneficiary is She Zhijiang, a businessman from China, head of Hong Kong’s Yatai International Holding Group and the main investor in the “resort city” of Shwe Kokko in Karen State, Myanmar.

The $15bn project envisaged casinos, luxury hotels and entertainment complexes. It is being built in partnership with Karen State’s Border Guard Forces (BGF)—former insurgents granted legal status.

Despite the founders’ ostentatious distancing from the scam centres, local residents told the BBC that scam firms occupy buildings throughout Shwe Kokko.

Back in 2020 Beijing denied any link between the project and One Belt, One Road after reports of possible illegal activity, and backed a probe into alleged violations.

In 2022 She Zhijiang was arrested in Bangkok on charges of running illegal online casinos. He calls the case politically motivated. Yatai International Holdings Group denies involvement in criminal activity, including human trafficking.

A second figure mentioned as likely involved in organising the compounds is Wan Kuok Koi, nicknamed Broken Tooth—a crime boss from Macau. He is the main investor in the Saixigang and Huangya special economic zones near Myawaddy.

Broken Tooth rose to power in the 1980s–1990s as a member of the 14K triad—one of Hong Kong’s biggest gangs. After a failed 1998 hit on a prosecutor, he was arrested. Released in 2012, he recast himself as a patriotic businessman backing China’s Communist Party.

Wan invests in casinos, property around Asia and cryptocurrencies—he even launched his own tokens, Dragon Coin and Hong (Triad) Coin.

In 2018 he founded the World Hongmen History and Culture Association. In 2020 it—along with two other Wan-linked organisations, the Dongmei Group and the Palau-China Hung Mun Cultural Association—was added to the US sanctions list for facilitating organised crime, including via cryptocurrencies.

It is unclear how the sanctions affected Wan’s business. The latest reports suggest the network of affiliated companies has kept expanding from South-East Asia to Africa, the Middle East and North America.

Thailand’s Office of the Attorney General, together with the Department of Special Investigation, is gathering evidence on human trafficking and scam call centres to issue arrest warrants for three Myanmar military officers. They include the aforementioned Col Karen National Army (KNA) figure So Chit Tu, Lt. Col. Mot Ton and Maj. Tin Win.

Experts note their deep business ties with Chinese gangs and their de facto impunity thanks to significant regional influence.

In May 2025 the KNA, So Chit Tu and his two sons, So Htu Eh Mu and So Chit Chit, were added to the US sanctions list for orchestrating large-scale cyber fraud, human trafficking and smuggling.

How the money is laundered

Reuters reporters traced the funds of several pig-butchering victims. All had invested via a fake crypto site and unwittingly sent money to scammers’ wallets.

After a series of transactions, the assets landed on wallets where KK Park pools its proceeds. Several direct transfers then moved the funds to other accounts. One address at the Binance crypto exchange received about $9.1m between February and October 2022. Journalists found the wallet had been registered by Wang Yi Cheng, a Chinese businessman in Bangkok.

In total, from January 2021 to October 2022 his account processed around $87.5m. The money was then routed to 50 other addresses, including exchange ones.

At the time the funds arrived, Wang was vice-president of the Thai-Asia Economic Exchange Trade Association, based in a building on Bangkok’s outskirts. The same building housed the Hongmen Overseas Cultural Exchange Center.

In February 2023 both offices were raided by Thai regulators, who suspected they fronted for organised crime and were linked to Wan Kuok Koi’s network.

Beyond shell firms, illicit funds are laundered via investments in casinos, special economic zones, the real economy and property across South-East Asia—especially in Cambodia and Laos.

Payment blockchain apps, proprietary cryptocurrencies and sprawling networks of unlicensed over-the-counter brokers help too. In April 2025 Thai authorities conducted large-scale raids on such firms’ offices. They uncovered more than 1,000 unauthorised transactions totalling over 425m USDT and traced flows to drug-trafficking and cyberfraud networks.

Cryptocurrency regulation in Myanmar

Myanmar’s central bank does not recognise cryptocurrency as legal tender; financial institutions and private individuals are banned from transacting with it.

Owning or trading digital assets can lead to imprisonment or fines. Activity is therefore largely informal.

In December 2021 the opposition National Unity Government, made up of supporters of the ousted Aung San Suu Kyi, recognised USDT as an official currency. It also considered launching a CBDC and a neobank on Polygon.

Pushback by states and rights groups

The Thai city of Mae Sot hosts an office of the rights group Global Alms, which rescues abducted people.

Volunteers Judah and Michelle mount rescues during transfers between compounds. Routes usually run through Thailand because it is faster and safer.

Victims contact the activists, who can then track their geolocation. They tail the kidnappers’ vehicle and signal the best moment for a getaway. Not every attempt succeeds.

Sometimes groups of forced workers stage escapes from the scam centres on their own.

Criminals exploit Myanmar’s fraught politics. The government disclaims responsibility because the compounds are in areas controlled by ethnic groups. Those groups, in turn, see no reason to shut down a steady revenue source. At every stage of trafficking, armed formations take a cut.

Thailand has taken the most decisive action in recent years. In February 2025 the authorities again cut electricity supplies to several border towns, switched off telecoms and tightened banking and visa policies.

This prompted scam-factory owners to release about 8,000 people. But the Thai authorities struggled to repatriate victims swiftly. While paperwork was processed, they were placed in temporary camps in Myanmar. The freed people complained of scant food and poor sanitation—sleeping on floors; samples from lavatories detected the pathogen that causes tuberculosis.

Thai authorities cannot always classify victims as trafficked; some are charged with immigration offences and moved to official detention.

China has been active, as its citizens make up the bulk of victims. Beijing demanded that Thai and Myanmar authorities grant senior police access to the scam compounds in the border zone.

Thanks to close ties with the political leadership of the self-proclaimed Wa state, China managed to halt the spread of centres there and free those held.

Similar scam compounds operate in Laos, Cambodia, Malaysia and the Philippines, but the presence of legitimate governments and relative political stability there allows more effective crackdowns.

Conclusions

Countries around Myanmar are actively fighting the network of scam compounds that strip hundreds of thousands of people worldwide of their freedom. But the decentralised nature of the crime makes the fight harder.

According to the latest UNODC data, as public awareness and law-enforcement pressure rise, criminal syndicates are pushing deeper into the region’s most remote, vulnerable and unprepared areas—and beyond.

Their success is aided by laundering vast illicit proceeds through cryptocurrencies and underground banking, which then seep into banking systems worldwide.

They are growing stronger and more influential. For now, law-enforcement efforts touch only the tip of the iceberg.

Read other pieces in the series: