What is a Sybil attack?

What is a Sybil attack?

This threat looms over any peer-to-peer network, including blockchain systems.

A Sybil attack entails creating a large number of fake identities or accounts to gain control over a protocol. This allows attackers to manipulate voting systems, consensus mechanisms or other governance processes.

The “identities” can be blockchain nodes, social-media accounts, wallet addresses or any other artefacts that let one actor pose as many participants.

In crypto, a Sybil attack targets control over a large number of network nodes. If an attacker succeeds, they can alter data in the distributed ledger, undermining the irreversibility of transactions. This jeopardises the reliability of information on the blockchain.

Such attacks can also capture user data, such as IP addresses, threatening privacy and security.

The term was first proposed in 2002 by Microsoft Research employee Brian Zill. The name was borrowed from Flora Rita Schreiber’s bestseller “Sybil” about a woman with dissociative identity disorder. In Russian translation the title appears as “Сивилла”, though “Сибилла” is also used.

What types of Sybil attack exist?

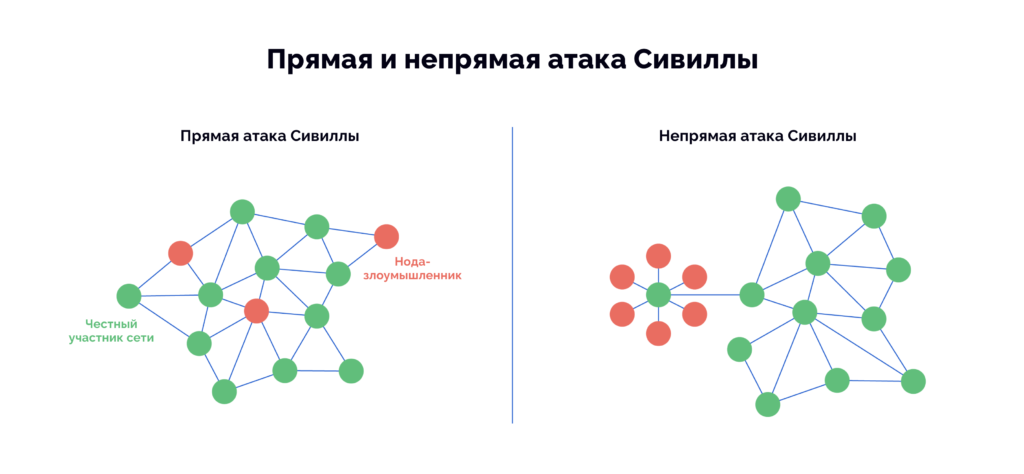

There are two main types of Sybil attack:

1. Direct: attackers try to influence the network by interacting directly with honest nodes. Their goal is to gain control over decision-making, voting procedures or consensus mechanisms.

2. Indirect: attackers avoid direct contact with honest nodes, instead using resources to covertly increase particular participants’ reputations, change the network topology or isolate parts of the network.

What is a 51% attack?

Often the end goal of “Sybils” is to carry out a 51% attack. This occurs when an attacker controls more than half of the network’s power, whether computing resources or staking.

In that situation the attacker can alter parts of the blockchain: reorder transactions, block their confirmation, halt validator payouts and execute double-spends.

Such influence enables sweeping changes that undermine the decentralised premise of blockchain systems.

What are examples of Sybil attacks?

Monero

The privacy-focused cryptocurrency Monero suffered a ten-day Sybil attack in autumn 2020.

An attacker tried to correlate IP addresses of nodes relaying transactions. However, the attack did not break the mechanisms that ensure privacy.

In April of the same year the Monero developers added a “covering tracks” feature as part of Dandelion++, making it significantly harder to link transactions to node IP addresses.

Ethereum Classic

Originally this was the Ethereum network. However, at the dawn of the ICO era in 2016, after the hack of The DAO in which more than $60m in ETH was stolen, a contentious hard fork was implemented to return funds to victims.

The new chain continued to use the name Ethereum, while opponents of the decision stayed on the old network (Ethereum Classic) with its own coin, ETC.

Since then the “original ether” has repeatedly suffered 51% attacks. For example, in August 2020 attackers three times managed to seize control of most of the network’s hashrate. This allowed them to carry out double-spends—moving ETC to their own wallets while also sending funds through exchanges. Across the series of attacks the organisers stole more than $7m in ETC.

Verge

In February 2021 the network of the cryptocurrency Verge (XVG), whose payments were supported by the popular porn site Pornhub, suffered a large-scale reorganisation of blocks. As a result, data on transactions and balances dated July 2020 disappeared from the blockchain.

CoinMetrics analyst Lucas Nuzzi called Verge’s reorganisation the deepest ever seen among top-100 cryptocurrency blockchains.

In April 2018 the Verge network suffered a 51% attack due to a bug in the code. A month later the problem recurred and affected all pools and miners.

How can Sybil attacks be mitigated?

In blockchain ecosystems, consensus mechanisms are the primary defence against Sybil attacks. Although different methods offer varying levels of protection, they make it much harder for attackers to create multiple accounts and succeed.

Proof of Work (Proof-of-Work)

In Proof-of-Work systems an attacker cannot simply use one node to create many false identities—substantial computing power is required to control the generation of new blocks, which is extremely difficult and expensive. The large number of Bitcoin miners, the high cost of equipment and electricity expenses make it harder for would-be attackers to obtain a significant share of the network’s computing resources.

Proof of Stake (Proof-of-Stake)

In blockchains with proof of stake, block creation can also be economically unattractive for attackers. For example, Ethereum requires users to post 32 ETH as collateral to participate as validators, and fraudulent actions carry serious financial consequences (slashing). As with Bitcoin, the presence of many participants with significant resources in staking makes it difficult for attackers to gain control over enough nodes to influence the network of the second-largest cryptocurrency.

Delegated Proof of Stake (Delegated Proof-of-Stake)

Some blockchains such as EOS and Tron use delegated proof of stake. These systems defend against Sybil attacks through “delegates”—a small group of trusted nodes elected by the community. Network participants are incentivised to act honestly; otherwise they risk losing their status and rewards, whose attainment requires substantial time and financial costs.

Proof of Personhood (Proof-of-Personhood)

Authentication by proof of personhood (PoP) confirms the uniqueness of a network participant via methods such as scanning a QR code or solving a CAPTCHA.

The Worldcoin project is notable for using iris scans as PoP. Another form of such authentication is KYC, where users prove their identity with documents such as a driving licence or passport.

Although these methods are effective at identifying unique users, they partly compromise privacy. KYC can deter those who prioritise confidentiality.

Beyond these methods, additional approaches to defending against Sybil attacks include ranking nodes based on reputation (Proof-of-Authority) and using social-trust or graph algorithms to detect anomalous node activity.

How do airdrop hunters use Sybil attacks?

In airdrop farming, “Sybils” seek extra rewards without directly manipulating the blockchain. Many projects’ campaigns use multi-level reward systems: for instance, one account with 100 transactions may receive fewer tokens than ten wallets with ten transactions each. This structure aims to distribute rewards more evenly among users rather than favour the most active participants.

However, this encourages hunters to create numerous wallets to obtain more tokens than by using a single address. Such tactics artificially inflate participant numbers, undermining the fairness of the airdrop and reducing the effectiveness of token distribution.

To counter this, many projects implement “Sybil” filtering mechanisms to identify and exclude dishonest participants before rewards are distributed. A prominent example is LayerZero, which partnered with analytics firm Nansen to detect linked wallets. In addition, the team launched a controversial bounty programme, encouraging community members to identify and report “Sybils”.

The stand-off between airdrop hunters and projects using such filters resembles a game of cat and mouse. As market participants devise new ways to evade algorithms, projects refine detection methods to preserve the fairness and transparency of reward distribution.

Рассылки ForkLog: держите руку на пульсе биткоин-индустрии!