Not only in Russia, but across the world, regulation of the open internet has tightened in recent years. The result is that the global web is starting to fray before our eyes.

In this ForkLog report, together with Ilya Perevalov, a technical expert at “Роскомсвободы”, we examine the degree of isolation in the Runet and the wider internet, and how enthusiasts are deploying mesh networks in real-world conditions.

The clampdown is in full swing

The reasons for unstable connectivity vary by region. Some places impose state restrictions in response to hostile external factors such as drone attacks; elsewhere, proper infrastructure is simply lacking.

Concrete examples are plentiful. According to the analytics resource “На связи”, 662 mobile-internet shutdowns of varying duration were recorded across Russia in June alone. A new record came in July: 2,099 shutdowns.

Large-scale shutdowns began in May—authorities said they were needed to ensure safety during the Victory Day parade. The government’s announced measures envisaged temporary mobile-internet blackouts in regions at higher risk of UAV attacks. According to “На связи”, by late June users were also reporting more problems with voice calls and fixed-line internet.

The topic grew especially heated after the SBU’s Operation “Pautina” (“Web”) in June, when kamikaze drones were guided to military airfields deep inside Russia using mobile internet.

Shutdowns have a serious impact on daily life. People struggle to pay online or by card, withdraw cash from ATMs, receive deliveries, access car sharing and much more. In some cases, they must take a bus to the nearest town with a working ATM just to withdraw money to buy food. Those whose work depends directly on the internet risk losing their income altogether.

“The internet was originally a network of networks, whose connectivity sometimes broke and they ended up isolated. At first this was for technical reasons, then because of peering wars (business plus selfishness plus perversity), and now—for political ones,” said Ilya Perevalov, a technical expert at Roskomsvoboda.

Such restrictions also endanger lives. For example, a communications blackout in the Udmurt Republic meant the air-raid alert at the Izhevsk Electromechanical Plant failed to trigger in time—three people were killed in the attack. And when mobile internet falters in emergencies, people waste precious minutes hunting for a signal to call an ambulance or rescuers.

Some localities have been in total shutdown for a month, with no relief. The situation is worsened by step-by-step—if not always logical—moves towards a “sovereign Runet”. In June 2025 Cloudflare confirmed that Russian authorities were limiting access to websites and services on its platform by throttling payloads to just 16 KB, rendering many sites practically unusable.

According to Perevalov, it is too early to speak of complete isolation.

“At least for now, Russian providers and internet exchange points (IX) still have good connectivity with foreign providers and IXs. That said, the trend towards traffic interference (which, alas, is growing abroad too) is very sad,” the expert explained.

This tightening coincides with the continued throttling of YouTube, the removal of VPN services from app stores, the blocking of Facebook and Instagram, and growing complaints about the performance of popular messengers.

“Given how unpredictable lawmakers are, it is hard to forecast anything, but the trend suggests more and more restrictions will be introduced. One would hope they will not go beyond traffic interference (that is, to physically cutting connectivity), but, as practice shows, when they really want something, nothing will stop them. Even if the entire civilian infrastructure goes down,” the Roskomsvoboda specialist added.

Becoming a node

The foundations of today’s mesh-network protocol were laid in the 1970s. Its first practical use was to establish field radio links for the US military.

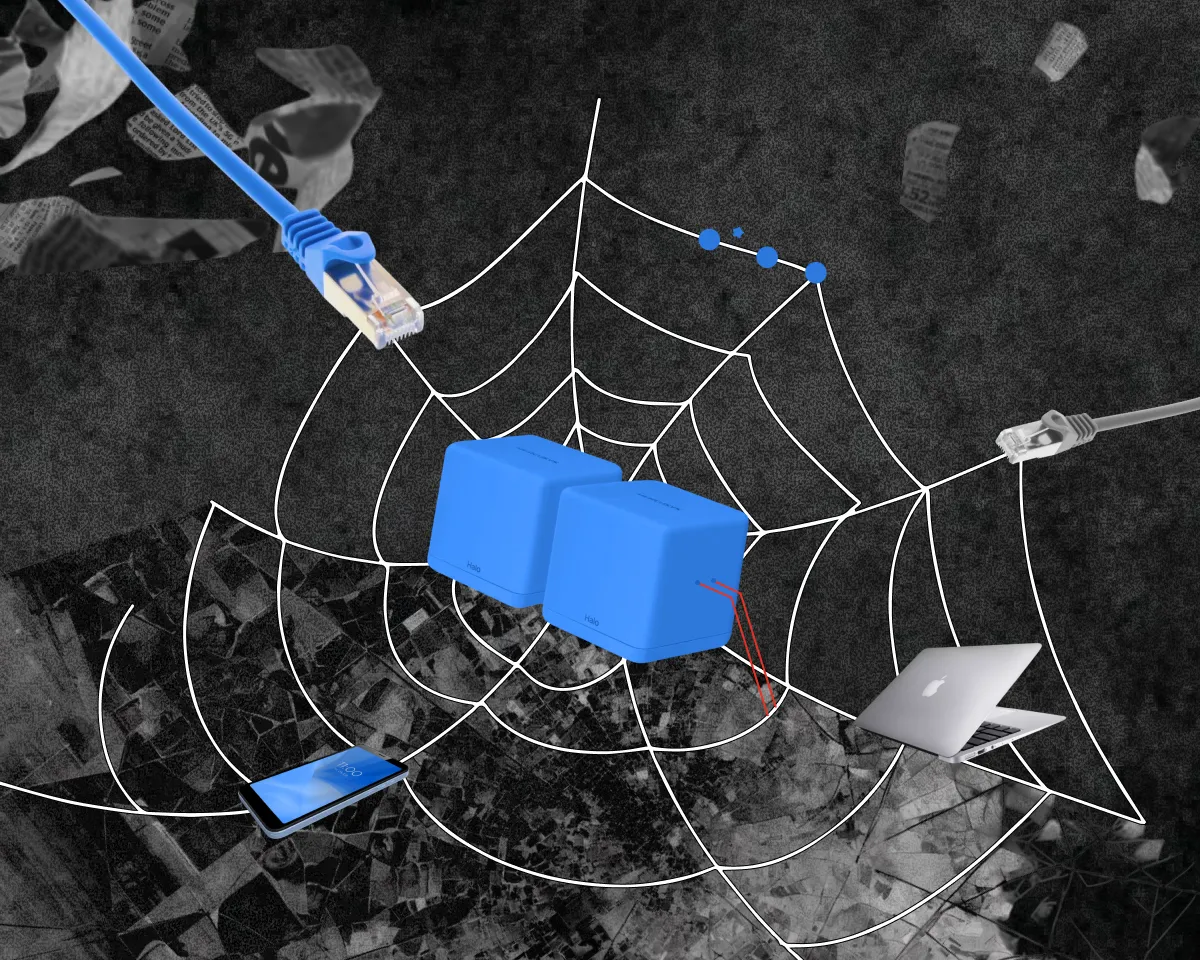

A mesh network is a cluster of computers built on a cell principle, in which workstations connect to one another and can act as a switch for the rest.

This architecture is highly fault-tolerant. Nodes interlinked “everyone with everyone” provide many routing options, so the failure of a single connection does not bring the network down.

In effect, the world wide web is a variety of mesh network. Each node (computer, server) forwards data packets and, based on their contents, directs them to the final address. There they are reassembled into an email, a video or an image. If one data block meets an obstacle, it can be sent along a different route. A well-designed mesh always has multiple paths from point A to point B.

Under constrained connectivity, a mesh can be laid using smartphones’ built‑in Bluetooth and Wi‑Fi modules, and sometimes additional radio transmitters.

Perevalov noted regulatory specifics for deploying mesh networks in Russia:

“The radio-frequency bands used by Wi‑Fi and Bluetooth are unregulated up to certain power levels. However, you can still ‘get in trouble’ for an overly powerful transmitter.”

Apple’s AirDrop function works on a similar principle when sending information to a nearby iPhone.

In a mesh, smartphones A and B can talk directly if they are close. Phone B may also communicate with device C, which is too far from A. B then acts as a relay, passing C’s message to A.

Mesh networks can be loosely grouped into four layers:

- the world wide web as the largest network;

- a local network of nearby smartphones with relays;

- a home network of smart-home devices;

- a personal network of portable gadgets.

For more than 50 years, researchers and enthusiasts have been finding new use cases for decentralised meshes. They connect IoT devices, build smart homes and create alternative coverage maps for settlements and entire cities.

One of many amateur networks worldwide blankets part of Austin, Texas. Enthusiasts have placed several solar-powered radio relays around the city. The stations operate at 906.875 MHz using the LoRa protocol. Links between them run on the open-source Meshtastic software.

Users can connect to these nodes via Bluetooth if close enough, or through their own portable nodes. Messages hop from cell to cell, extending coverage, but only those with the key can read them. Thanks to their autonomy, the network keeps working during total power and telecom outages.

Once a week, all owners of “flying nodes” simultaneously lift drones with antennas to altitude to maintain links. They broadcast a few messages—such as an invitation to a chat—and create activity.

In Perevalov’s view, mesh deployments still attract mostly hobbyists:

“Formally they can help, of course, but given the global experience with meshes (when only a handful of enthusiasts are involved and mass adoption is very far off), I’m rather sceptical and don’t think a trend towards change will emerge.”

And the reply is silence

Mesh-based messengers for mass use appeared in 2014. One of the first cross-platform mobile apps was FireChat. It won real popularity during that year’s Hong Kong protests; in less than a day, 100,000 new accounts were created. The app’s last official update came in 2019.

It was developed by Open Garden, whose open-source software had earlier been used by One Laptop Per Child. The charity provided tablets to residents of developing countries, linking them into a mesh. It was an ideal solution for villages with almost no internet. Devices could share a single access point, distributing connectivity across a wide area—much like today’s Wi‑Fi extenders built on mesh technology.

Today there is a large number of mesh apps. iOS and Android users can install popular Briar, Bridgefy, Walkie Talkie, Air Chat, Berkanan and others.

“Mesh-network technology really isn’t new. As before—and now, despite the abundance of tools—very few are willing to use it. The pluses of such decentralised communication may reveal themselves only under non-regulation. If lawmakers come up with another regulatory nastiness, then, within the law, it may all end before it even begins,” the expert said.

On 7 July 2025, saw the release of the “private” messenger BitChat by Twitter founder Jack Dorsey. The open-source app is non-commercial. According to Dorsey, it was created during “vibe-coding” over a weekend.

my weekend project to learn about bluetooth mesh networks, relays and store and forward models, message encryption models, and a few other things.

bitchat: bluetooth mesh chat…IRC vibes.

TestFlight: https://t.co/P5zRRX0TB3

GitHub: https://t.co/Yphb3Izm0P pic.twitter.com/yxZxiMfMH2— jack (@jack) July 6, 2025

According to the white paper, BitChat is a fully autonomous messaging system over Bluetooth Low Energy. It allows a mesh to be created without the internet, accounts, servers or phone verification.

Each device acts as a node, forwarding encrypted messages over distances of up to 300 metres or more thanks to relay mechanisms and TTL routing.

One of BitChat’s key features is privacy. The Panic Mode function instantly deletes all data after triple‑tapping the logo.

The developers note that some options, including private messages, have yet to pass an external security audit, so BitChat remains an experimental project.

Despite scepticism about meshes in the global context, Perevalov believes the technology has a chance:

“A mesh structure has a huge plus: if there are very many participants (at least every third flat in every building in every city) and at least half of them have connectivity to other cities, or even countries, then it will be an unblockable network that is very resilient to failures. Protocols that can reconfigure links when participants drop out have existed for a long time. The only problem is the number of participants and their fragmentation.”

The main challenge for such systems remains the engagement of each cell—an active, responsible person. Perhaps intensifying regulatory pressure worldwide will spur change. For now, when you open BitChat, the reply is silence, extending a little more than 300 metres.