‘Q Day’ jitters: how bitcoin’s developers plan to thwart quantum computers

On December 10, researchers at Google Quantum AI unveiled a new quantum chip, Willow. The news rekindled the crypto community’s fears about a quantum threat to bitcoin—a topic that has surfaced periodically.

After Google’s release, though, “quantum FUD” seemed to be taken far more seriously. By December 18 the Bitcoin Improvement Proposal titled Pay to Quantum Resistant Hash (P2QRH) had been assigned a number (BIP-360).

Together with the team at the bitcoin mixer Mixer.Money, we examine how developers are preparing for “Q Day”—a possible moment in the future when the first cryptocurrency could become vulnerable to quantum attacks.

What the quantum threat entails

Bitcoin’s protocol uses public-key cryptography to make transactions. When a new wallet is created, it generates a mathematically linked pair of keys—public and private. The private key must be kept secret; the public key is visible to all. This enables digital signatures created with the private key, which anyone can verify using the corresponding public key.

The security of this pairing rests on a one-way function: a public key is easily derived from a private key, but not the other way round. In 1994, however, the mathematician Peter Shor published a quantum algorithm capable of breaking this assumption. Any organisation with a cryptoanalytically relevant quantum computer (CRQC) could use it to derive a private key from its public counterpart.

Accordingly, the author of BIP-360, writing under the pseudonym Hunter Beast, stresses that preventing public keys from appearing on-chain is a crucial step toward quantum safety.

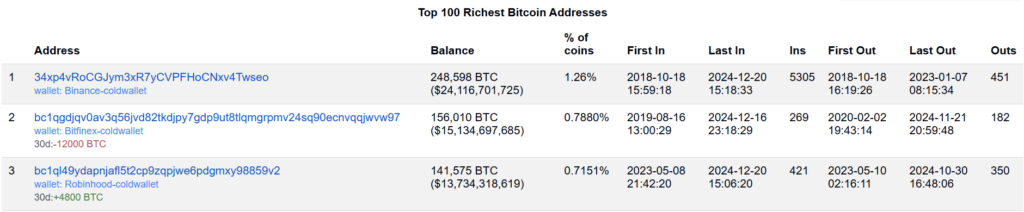

Back in 2019 the bitcoin developer Pieter Wuille estimated that around 37% of supply could be at risk because public keys are revealed on-chain—either coins were received directly to public keys or addresses were reused.

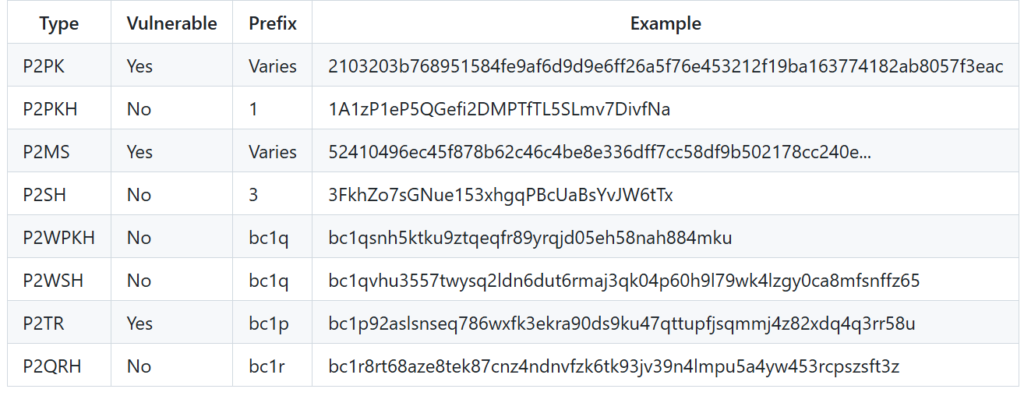

In early versions of the software, coins could be received in two ways:

- Pay-to-Public-Key (P2PK). The public key itself serves as the recipient’s address. Coins mined by bitcoin’s creator, Satoshi Nakamoto, sit on such outputs and could be compromised by a CRQC.

- Pay-to-Public-Key-Hash (P2PKH). The recipient’s address consists of a hash of the public key, so the latter is not revealed directly on-chain.

As long as no spend has been made from a P2PKH address, its public key does not appear on-chain. It becomes known only when the owner spends from it.

After a spend, it is best practice not to reuse the address. Modern wallets are configured to generate a new address for every transaction—primarily for privacy rather than quantum resistance.

Even so, in 2024 ordinary users, exchanges and custodians still hold hundreds of thousands of bitcoins on reused addresses.

Hunter Beast distinguishes two types of quantum attack:

- Long-range. The public key is known, giving attackers unlimited time to crack it;

- Short-range. The attack must be executed quickly while the transaction sits in the mempool.

The latter becomes possible because the public key is revealed when coins are spent. Pulling this off would require powerful CRQCs because it must be done within a brief window. In the early stages of CRQC development, long-range attacks—where the public key is known in advance—are more plausible.

Short-range attacks target any transaction in the mempool, whereas long-range attacks focus on:

- P2PK (Satoshi’s coins, CPU miners);

- reused addresses (of any type);

- wallet extended public keys (also known as xpubs);

- Taproot addresses (beginning with bc1p).

The table below informs bitcoin users whether their coins are vulnerable to a long-range attack:

Notably, the last major bitcoin upgrade—Taproot (P2TR)—sparked a debate in 2021 precisely because of quantum vulnerability concerns for this address type. At the time, Blockstream co-founder and bitcoin developer Mark Friedenbach published “Why I’m against Taproot”, expressing reservations about activating the upgrade amid progress in quantum computing.

In an interview with Unchained, Hunter Beast explained the Taproot vulnerability:

“Unfortunately, Taproot contains an onchain short version of the public key—the x-coordinate of the elliptic-curve point. That information is sufficient to recover the full public key.”

Satoshi’s shield

Coinbase transactions paying to public keys (P2PK) continue up to block #200,000. Most of them hold 50 BTC.

Hunter Beast calls these coins “Satoshi’s shield.” In his view, any address with a balance below 50 BTC is uneconomic to attack.

“For this reason, those who want to be prepared for a quantum emergency are advised to store no more than 50 BTC on a single unused Native SegWit address (P2WPKH, bc1q). This assumes the attacker is financially motivated and not, say, a state actor intent on undermining confidence in bitcoin,” he argues.

QuBit

BIP-360 could become the first proposal under QuBit—a soft fork to make bitcoin resilient to quantum attacks.

“A qubit is the fundamental unit of quantum computation, and the capital letter B stands for bitcoin. The name QuBit also somewhat rhymes with SegWit,” the BIP-360 text notes.

The proposal introduces a new address type beginning with bc1r. P2QRH would be implemented atop P2TR, combining classical Schnorr signatures with post-quantum cryptography.

“Such hybrid cryptography avoids lowering security should one of the signature algorithms prove vulnerable. The key difference between P2QRH and P2TR is that P2QRH encodes a hash of the public key. This is a significant departure from how Taproot works, but it is necessary to prevent public keys from being exposed on-chain,” the author of BIP-360 argues.

P2QRH uses the HASH256 algorithm to hash the public key. This reduces the size of new outputs and boosts security by keeping public keys off-chain.

BIP-360 proposes introducing FALCON signatures first. After that, SQIsign and other post-quantum algorithms—SPHINCS+, CRYSTALS-Dilithium—would be added. The specification for SQIsign says it has the smallest total size among known post-quantum schemes.

FALCON is roughly four times larger than SQIsign—and about 20 times the size of Schnorr signatures.

“FALCON is a more conservative approach than SQIsign. Its use was recently approved by NIST, which simplifies deployment thanks to the scientific community’s consensus. Even so, SQIsign signatures are about five times larger than Schnorr signatures. This implies that, to maintain today’s transaction throughput, the witness discount likely needs to be increased in the QuBit soft fork. This will be specified in a future QuBit BIP,” the proposal states.

Hash-based cryptosystems are more conservative and time-tested. Lattice-based cryptography is comparatively new and introduces fresh security assumptions to bitcoin, but its signatures are smaller and may be seen by some as a reasonable alternative to hash-based schemes. SQIsign is far more compact, but it relies on a new form of cryptography and, at the time of writing, had not been approved by NIST or the wider community.

According to BIP-360, including four cryptosystems is motivated by the need to support hybrid cryptography, especially for large outputs such as exchange cold-storage wallets. A new library akin to libsecp256k1 will be developed for adoption.

Hunter Beast allows that, after P2QRH is deployed, there may be demand for Pay to Quantum Secure (P2QS) addresses:

“There is a distinction between cryptography that is merely resistant to quantum attacks and cryptography that is secured using dedicated quantum hardware. P2QRH is quantum-resistant, whereas P2QS is quantum-secure. Signing would require specialised quantum hardware, but the public keys would remain verifiable by classical means. P2QS would require additional BIPs.”

For now, quantum-cryptography hardware is not widely available, so quantum-resistant addresses may serve as an acceptable interim solution.

The quantum transition

In October 2024, researchers at the University of Kent published an analysis estimating the time required to move bitcoins to quantum-resistant addresses.

“We calculated a lower bound on the cumulative time needed for the above transition. It is 1,827.96 hours (or 76.16 days). We also show that the transition must be completed before quantum devices that break ECDSA appear, to ensure bitcoin’s security,” the paper states.

In his presentation at Future of Bitcoin 2024, Casa’s CTO Jameson Lopp calculated that migrating all UTXOs would take at least 20,500 blocks (about 142 days).

“But it’s far more likely to take longer, because that’s the most optimistic scenario in which the bitcoin network is used exclusively for migration. Such expectations are, of course, unrealistic. The process could take years. We should be conservative and assume it may take many years,” Lopp argues.

He concludes that even if the quantum threat seems distant, it is better to discuss it “sooner rather than later.”

Conclusions

Over the years bitcoin has faced varied bouts of FUD: the spectre of a 51% attack, government bans, altcoin competition and, now, quantum computing. These concerns surface regularly, yet the first cryptocurrency has so far proved resilient.

“After spot ETF approvals and BlackRock’s educational videos on bitcoin, nobody is talking about bans anymore. Fears of a 51% attack were always overstated, and its impact on the network is extremely limited,” note representatives of Mixer.Money.

The quantum threat is deeper, but the proposed QuBit soft fork shows developers are well aware of it. Quantum resistance also features in Ethereum’s roadmap, from which the bitcoin community can glean useful lessons.

“It’s worth noting, however, that Ethereum can execute a quantum transition with another hard fork. Bitcoin is more complex: there are no hard forks, and Satoshi’s coins cannot simply be frozen—doing so would undermine the first cryptocurrency’s foundational principles,” say the team at Mixer.Money.

The fate of “Satoshi’s shield” and other coins that do not move to quantum-resistant addresses remains unclear. The bitcoin developer Luke Dashjr suggests that, in future, they might be treated as akin to mining.

“In the end, 37% of the supply mined by quantum computers is no different from 37% mined by ASIC miners,” he said.

Рассылки ForkLog: держите руку на пульсе биткоин-индустрии!