Recommender systems: what they are and how they work

What are recommender systems?

Recommender systems are algorithms that select relevant goods and services based on user data.

The technology is a subfield of machine learning.

When did recommender systems emerge?

Recommender systems are relatively new. In 1990 the technology was first mentioned by the Swedish scholar Jussi Karlgren, who described it as “a digital bookshelf”. The work laid the foundation for his later research.

In the 2000s recommendation algorithms began to permeate e-commerce. One of the pioneers was Amazon.

In 2006 Netflix, then a DVD-by-post subscription company, launched a competition for the best recommendation algorithm with a $1m prize. To claim it, independent developers had to improve the accuracy of the recommendation engine by 10%. In 2009 the prize went to the team BellKor’s Pragmatic Chaos.

In the 2010s recommender systems arrived on social media. Today most popular platforms have abandoned the chronological feed in favour of an algorithmic one.

How do recommender systems work?

Two principal approaches are used today in recommender systems: collaborative filtering and content-based models.

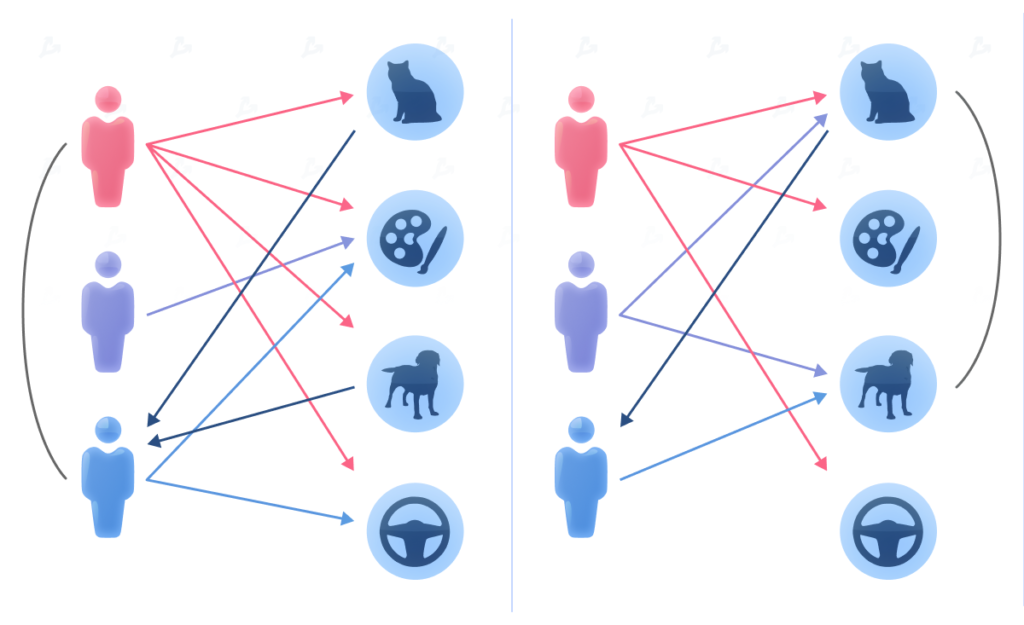

The core idea of collaborative filtering is to generate recommendations using data from other users with similar interests. Filtering can be user-based or item-based.

The main task of a user-based algorithm is to find users with the most similar tastes based on the products they have consumed and the ratings they have given. Suppose Anna and Vadim bought juice, a bun and yoghurt. It is also known that Maksim often buys juice and buns. He should therefore be recommended yoghurt.

Item-based recommendations tackle the problem from the other side: find similar items and see how they were rated before. Let us try to infer whether Maksim likes yoghurt. We know he likes juice and buns. As a food product, yoghurt has similar characteristics. We can therefore assume he will like it.

The aim of collaborative filtering is to find a user who has rated a particular item and to compute the correlation coefficient between the vectors of their ratings across all items in the database. A common method is k-nearest neighbours.

At the centre of a content-based model is the item itself. User ratings are not required for the algorithm to work. What matters are properties that characterise the item: author, genre, country of origin, manufacturer, and so on. Not all attributes are relevant to the consumer, so it is best to focus on the key ones.

Content-based models have grown popular in recent years. They do not require lengthy training; developers can start recommending items right away.

There are drawbacks. Many users have noticed that after searching for a particular product on Google they are “chased” by ads offering to buy it in some online shop. To reduce complaints about irrelevant ads, developers complement such algorithms with knowledge-based models. These also do not rely on ratings, using only user and item profiles.

How do recommender systems collect data?

Data for recommendation algorithms can be collected explicitly or implicitly.

Explicit methods include asking users to rate items on a scale, rank them from best to worst, compare two similar products, or compile a favourites list. The key point is that the user understands their data are used by algorithms and consents to processing.

With implicit methods, site visitors are not always aware that their actions may feed recommender systems. This includes cookies, Google or Facebook ad trackers, detailed analysis of interactions with videos, and so on.

Governments in many countries typically require sites to notify visitors about such data collection. Users, however, cannot always opt out.

Where are recommender systems used?

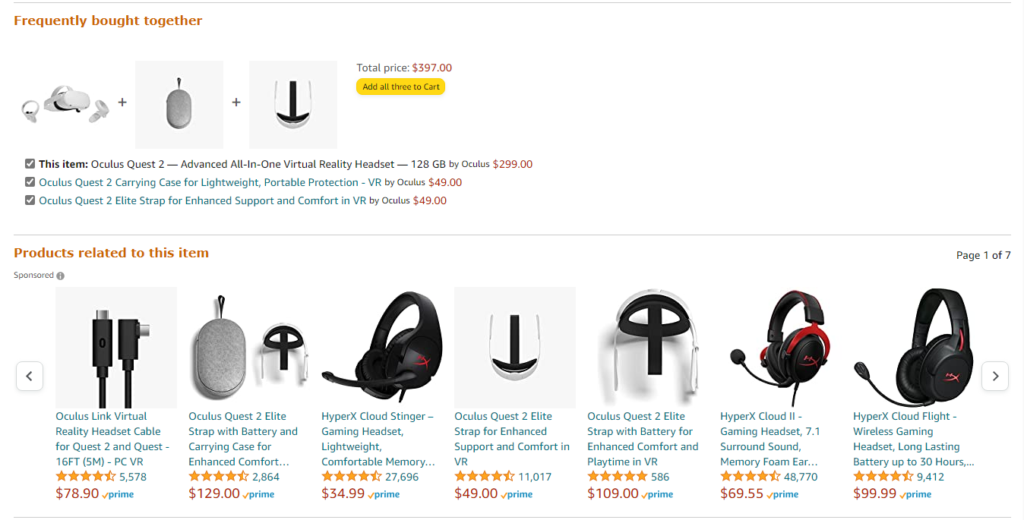

As noted, recommender systems are widely used in e-commerce. Online shops use them to suggest relevant products in the “You might also like” section or to offer complementary items directly in the basket. If a product is out of stock, algorithms can surface alternatives.

Email newsletters also often contain personalised recommendations.

Retailers such as Amazon, Ozon and Wildberries use these algorithms.

Major streaming services also use recommender systems, including Netflix, Spotify, Apple Music, Yandex Music, YouTube, Megogo and others.

Recommendation algorithms are widespread on social networks. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, VKontakte and others have for years shown users content assembled by algorithms. Only a few allow switching to a chronological feed.

What problems do recommender systems have?

Recommender systems have several limitations. One is the cold-start problem—when the algorithm lacks sufficient data to operate well. This is typical for a new or unpopular item rated by few users, or for an atypical consumer whose preferences diverge markedly from the average.

In such cases ratings are adjusted artificially. For example, instead of a simple mean, a smoothed average is used. With few reviews, an item’s rating will tend towards a “safe average”; once enough real ratings accumulate, the artificial smoothing is switched off.

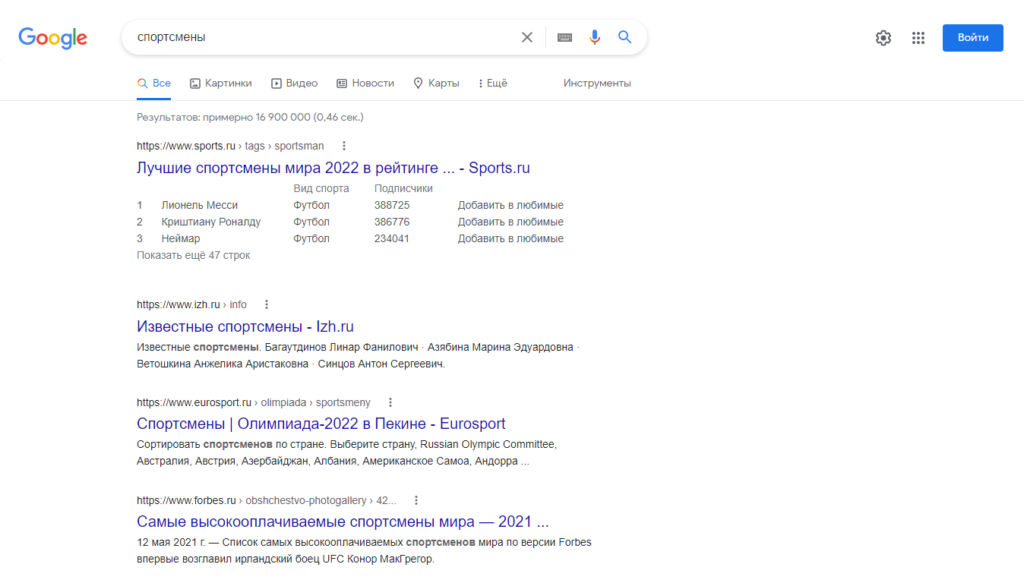

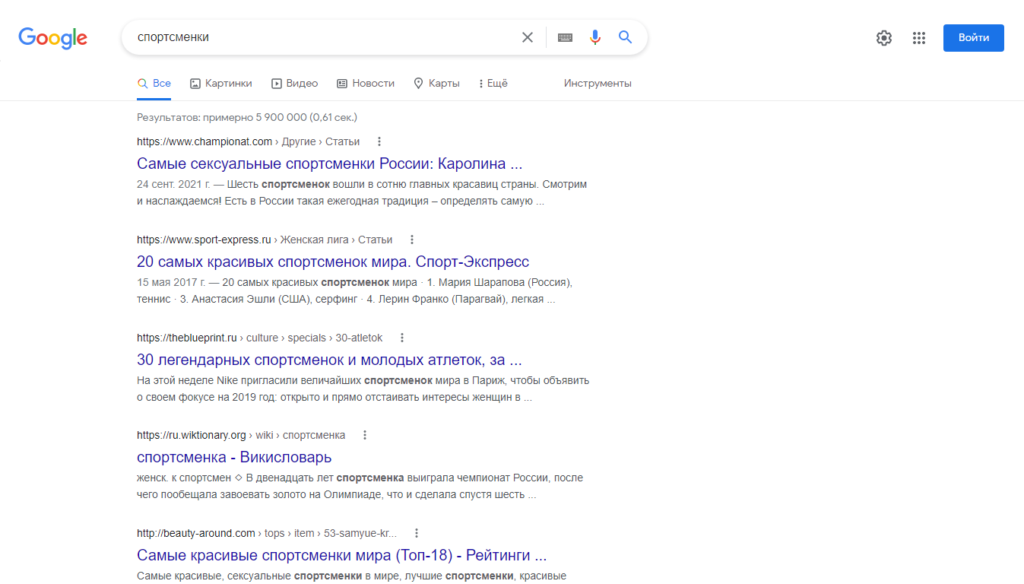

Another issue is bias. Poorly tuned algorithms, built-in stereotypes and user behaviour can all distort rankings.

In 2021 Facebook’s advertising algorithms disproportionately showed different job ads to men and women. Twitter’s auto-cropping tool for the home feed tended to focus on young, slim women.

In both cases developers quickly fixed the errors, but that is not always possible. Google is frequently criticised over how its recommendation algorithms work.

For example, results for the queries “athletes” and “female athletes” differ markedly. For men the algorithms surface articles about professional achievements. For women the system returns various rankings of “attractiveness” and “sexiness”.

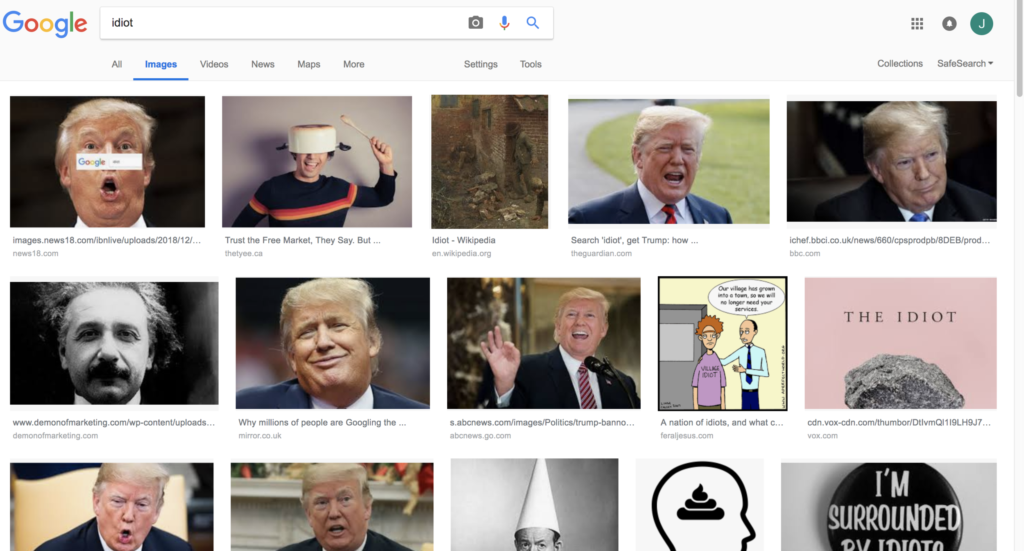

Search results can be influenced not only by users but also by bots. In 2018 Reddit users staged deliberate manipulations of Google’s algorithms so that a photo of former US president Donald Trump appeared for the query “idiot”.

During a congressional hearing on the incident, the company’s chief executive Sundar Pichai said that employees do not intervene in ranking. According to him, algorithms do this on their own, scanning millions of search strings and ranking them by more than 200 parameters.

Developers of recommender systems can also exploit algorithmic bias. In October 2021 a former Facebook employee published documents showing the deliberate use of “harmful” tools on the platform. She said top managers knew the algorithms were intolerant towards vulnerable groups. But the company was slow to fix the errors because such content drove stronger user engagement and boosted advertising revenue.

Subscribe to ForkLog news on Telegram: ForkLog AI — all the news from the world of AI!

Рассылки ForkLog: держите руку на пульсе биткоин-индустрии!