Silicon Tanks: “Stay hungry, stay foolish” — Stewart Brand

Stewart Brand’s ideas that foreshadowed bitcoin and the Lindy logic of maintenance.

Stewart Brand is neither a programmer nor a cryptographer. He is a biologist, a former soldier and a veteran of the 1960s psychedelic scene. Yet his ideas drew a direct line from hippie communes to cypherpunk forums and decentralised networks.

ForkLog examines how the author of the Whole Earth Catalog articulated the core principles of digital freedom, why information wants to be both expensive and free at once, and how the idea of “perpetual maintenance” explains Bitcoin resilience.

Origins

Silicon Valley was not always the preserve of venture capitalists and hoodie-clad entrepreneurs. Its foundations were laid by the ideals of the 1960s counterculture. The chief architect linking rebel hippies and early hackers was Brand. His biography doubles as a map of the internet’s development: from the acid-soaked prose of Ken Kesey to the philosophy of open source and distributed ledgers.

Most people know Stewart Brand indirectly — through Steve Jobs’s famous address, which quoted the closing line of the Whole Earth Catalog: “Stay hungry. Stay foolish.” But he is far more than the author of a single line.

At 87 he is still rethinking how civilisation functions: from writing philosophical tracts about repairing everything to revising his own domestic set-up. Even the recent sale of his storied floating home is more than a property deal; it illustrates his theory of maintenance systems that keep our complex world afloat.

Across his life, Brand’s views have evolved, often angering former allies. In Whole Earth Discipline he defied orthodox environmentalism by backing genetic engineering, urbanisation and nuclear power. Brand called this a “turquoise” mindset: unlike “greens”, “turquoises” see technology not as a menace but as a tool to save the planet.

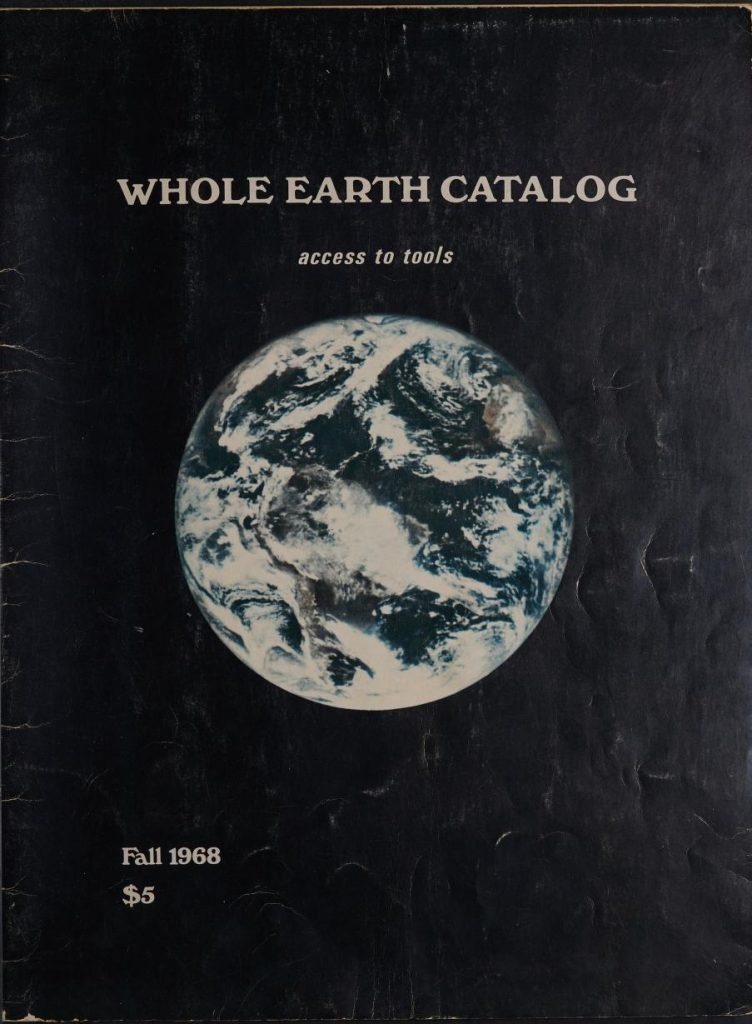

Access to tools: Google on paper

In 1966 Brand was an active participant in countercultural experiments and a member of the Merry Pranksters led by Kesey.

Their origin story is worth a detour. In 1959 Kesey was offered LSD and mescaline several times a week under medical supervision, then asked to solve simple maths problems. He was paid for taking part.

Sixteen years later he learned the project had been part of a broader American intelligence experiment into manipulating people with psychoactive substances. Easy access to drugs and money emboldened Kesey, who dreamed of building a commune (Arcadia).

Having procured a key to the cabinet where the substances were kept, he smuggled them to Arcadia and threw lavish parties. These gatherings — funded, effectively, by the CIA — entered literary history thanks to Kesey’s friend Allen Ginsberg.

Amid this ferment of ideas, Brand began a campaign built on a simple question: “Why have we not yet seen a photograph of the whole Earth?”

He handed out badges bearing the question, believing that seeing the planet from afar would change human consciousness, revealing it as a fragile “island in the black vacuum”. The effort paid off: in 1967 a satellite produced just such an image, which graced the cover of the first Whole Earth Catalog.

The Catalog, launched in 1968, was “Google in paper form” 35 years before the search engine. Brand created not merely a magazine but an annual almanac — a compendium of resources, “access to tools”: from guidance on construction and farming to reviews of early personal computers. Its motto declared: “We are as gods and might as well get good at it”.

In 1985 Brand, together with Larry Brilliant, launched The WELL. It was among the first virtual communities.

If the Catalog offered tools for physical survival, The WELL provided a space for intellectual survival. Veterans of the counterculture met young computer geeks.

The WELL became a prototype for modern DAOs. There was little top-down moderation, but strong internal norms flourished. Brand’s rule “You own your own words” was revolutionary. It placed responsibility for content on the author, fostering trust and reputation rather than anonymous chaos.

It was in The WELL and similar BBS that the cypherpunk movement took shape. People used to free exchange began to think about protecting that freedom from state surveillance. John Gilmore and other cryptography pioneers were part of this ecosystem.

The WELL taught people to coordinate online without central command. And although Brand has issued no direct pronouncements on Bitcoin or modern DAOs (he is more distant from digital anarchism), many systems in crypto were built in analogy with early digital communes.

The price of information freedom

In 1984, at the first Hackers’ Conference, Brand said in conversation with Steve Wozniak a phrase often quoted without context: “Information wants to be free”.

In full, the thought reads as a paradox that prophetically describes modern blockchains:

“On the one hand, information wants to be expensive, because it is very valuable. The right information in the right place changes your life. On the other hand, information wants to be free, because the cost of copying it decreases. These two sides fight each other.”

Its modern resonance goes far beyond piracy or open source:

- Freedom of dissemination: Bitcoin code is open, the mempool public. Anyone can download the transaction history.

- High cost: to mine digital gold you must expend energy (Proof-of-Work).

Brand foresaw the conflict between the ease of copying data and the value of trustworthy information. Bitcoin addresses the paradox by making information free to read but costly to falsify.

A philosophy of maintenance: why systems endure

In recent years Brand has arrived at perhaps the most mature strand of his philosophy — the concept of technical maintenance, which he sees as the essence of civilisation. We are used to celebrating innovation, but it is routine care — of things, homes, bodies and the planet — that lets life continue.

This philosophy is evident in his personal life. Brand and his wife, Ryan Phelan, recently put their Sausalito home up for sale. It is not just a house but Mirene, a 64-foot tugboat built in 1912.

He bought it in 1982 and spent decades restoring it, turning a working vessel into a cosy residence with a library. Life on board, Brand says, feels like living inside “a finely crafted musical instrument”.

Selling the home he tended for more than 40 years marks a new phase, but the ethic of care remains central to his legacy.

What does this have to do with crypto?

Bitcoin is often criticised for slow development and the absence of constant, feature-stuffed forks. In Brand’s terms, resilience matters more than novelty. Miners, node operators and Bitcoin Core developers perform the global maintenance of the network.

Brand teaches that the longer a system exists and is maintained, the more reliable it becomes (the Lindy effect). The Long Now Foundation he established is building a clock inside a mountain in Texas designed to run for 10,000 years. It ticks once a year; the cuckoo appears once a millennium. The aim is to shift humanity’s planning horizon beyond quarterly reports or electoral cycles to centuries, instilling responsibility to distant descendants.

Cryptocurrencies with immutable blockchains are a digital attempt at such a clock: systems that keep ticking regardless of changes in government, war or corporate bankruptcy. Although Brand himself treats crypto-assets cautiously, his ideas about digital self-maintenance and distributed responsibility can be read as a prologue to Bitcoin.

The path from the Merry Pranksters’ commune to anonymous developers defending privacy with code is one story about tools belonging to people rather than corporations. And about freedom requiring constant, routine maintenance.

Brand remains a singular figure capable of shifting whole generations’ perspective. How does it work? First, he showed us Earth from space. That is not just a pretty picture but proof that we live on a “spaceship” with a closed resource loop and no external rescuer. From this flows the idea of personal responsibility (as with a ship’s crew) and the need to husband resources — whether the planet’s ecology or the hygiene of the digital realm.

Starting with the desire to see Earth whole, he taught us to perceive the links between ecology and electronics, between the freedom of information and responsibility for the future. Even now, as he approaches his tenth decade, he offers not ready-made answers but tools for thought, reminding us that the most important work is not only making the new, but caring for what we already have.

Рассылки ForkLog: держите руку на пульсе биткоин-индустрии!