The Battle for P2SH: How the First Major Bitcoin Developer War Ended

Over Bitcoin’s history, it has endured many dramatic moments, not all of which were merely swings in the coin’s price. One need only recall the events surrounding the activation of the Segregated Witness protocol, the Bitcoin Cash hard fork, and the wars that preceded them over block size.

But the first truly large clash within the developer community was the question of activating P2SH — the first upgrade that occurred after the departure of Satoshi Nakamoto.

Peter Rizzo and Aaron van Wirdum recounted those events in a Bitcoin Magazine article. Its adapted translation is presented below.

****

«Push the date back by two months. OP_EVAL is not ready yet.»

Gavin Andresen had been working for a long time to avoid such a verdict. A single phrase sent from Russell O’Connor’s computer halted months of work on implementing the first post-Satoshi Nakamoto upgrade to Bitcoin Core.

The proposed approach, Andresen called the quickest path to safer Bitcoin wallets. However, as O’Connor found, it contained a vulnerability that could allow an

In other words, through OP_EVAL one could disrupt the operation of nodes and, consequently, the entire Bitcoin network.

«It took me a full 70 minutes to find this bug. Guys, you should stop and really understand Bitcoin,» — wrote O’Connor.

This was Andresen’s first major setback as the project’s new lead, and he sought to dispute O’Connor’s conclusions. In his view, dropping OP_EVAL would waste months of writing and testing, and would also leave users without tools to defend against trojans and other malware that threatened wallets at the time.

OP_EVAL aimed to create simple multisignature wallets that would allow recovering bitcoins even with lost backups. The team also envisaged bank-like alert services designed to prevent theft and fraud. All within the framework of transactions already familiar to users.

Yet for those who saw danger in moving too fast, O’Connor’s warning proved sufficient.

«I would remind everyone that we are risking a system worth more than $20 million. It’s not just software at stake—everything must be utterly reliable», — wrote developer Alan Reiner.

The failure to activate OP_EVAL also carried another important consequence. Very few in 2011 truly understood Bitcoin’s code, and even fewer possessed the knowledge and skills to defend it.

How should developers be organised? What responsibilities do they bear to users? How to activate upgrades if it is unclear who has the final say? All these questions soon became central in the first major war among Bitcoin’s developers.

Power Transfer

Typically, open-source projects are led by their founders, who coordinate work with contributing developers. And Bitcoin was no exception. In the early years, Satoshi Nakamoto acted as lead developer and de facto dictator. Without broad discussion in the community, he introduced eight upgrades and gradually stepped back.

By the end of 2010 Nakamoto’s name had been removed from Bitcoin.org, and the de facto project leader became Gavin Andresen, previously known for his work in 3D graphics software. The handover was unusual: it consisted of a short public note and a confidential transfer of the system alert key.

Gavin Andresen. Photo: 93.9 & 101.5 THE RIVER.

At that time, for a small group of Bitcoin developers, this was not a particular problem. They were more focused on critical vulnerabilities, while Andresen had enough free time and enthusiasm to lead the work. There were many issues demanding urgent resolution: faster synchronization, better software testing, and a rising tide of reports of compromised wallets and reputational losses from theft. These issues were prioritised, with the majority agreeing.

Multisig

The solution to the wallet-hacking problem, as Andresen discovered, was proposed by Satoshi Nakamoto himself. The Bitcoin code already included the ability to conduct transactions under multi-signature conditions.

The multisignature system (multisig) allowed private keys to be stored on several devices in different parts of the world, or split between the user and wallet provider. This meant that to steal coins, attackers would need to compromise several targets.

The concept quickly inspired Andresen, and in the developer mailing list he passionately urged more active action in this direction.

«What concerns me most is that it would take only a few days to agree on how to do this right, yet six months have passed and there is still no consensus. Meanwhile, wallet thefts continue».

These concerns were not unfounded—Nakamoto’s implementation had several significant drawbacks. Chief among them was the incompatibility of transactions with the standard Bitcoin address format, which required longer addresses. For this reason, when sending funds to multisig addresses, transactions took more space and demanded higher fees. Moreover, these fees were paid by the sender, not the recipient.

Consequently, multisig transactions were labelled “non-standard.” This meant that if a node received such a transaction, it would simply ignore it. There were also no guarantees that miners would include such transactions in blocks.

OP_EVAL

To unlock the full potential of the multisig idea, Andresen supported a new opcode — a command used by nodes to determine whether a new type of transaction was valid, and under what conditions, if so.

OP_EVAL relied on hashing data and was first proposed by the ByteCoin developer. The core idea was that users could hash instructions describing the conditions under which Bitcoins could be spent in the future (including multisig wallets), including this hash in the transaction. The user paid for the extra size of the transaction when spending coins, but the extra data did not place a heavy burden on the network.

The proposal was well received, and Andresen did everything possible to accelerate its activation.

«Security is one of the top priorities; I would like to see secure addresses in user signatures on the forum within a year»

— wrote him [in October 2011].

Not everyone, however, agreed with Andresen on the need for as rapid activation as possible. OP_EVAL would indeed be a major network upgrade, which already held millions of dollars in assets. British developer Amir Taaki, then barely in his twenties and a committed anarchist, believed more time was required to assess the proposal.

«At first glance the idea seems strong. But rush in the blockchain is probably not the wisest course… Bitcoin won’t skyrocket tomorrow, so I don’t see a problem in delaying such changes», — he replied to Andresen.

The situation was further complicated by the fact that implementing OP_EVAL in the protocol, as developers believed, would split Bitcoin’s blockchain into two networks, each operating under its own rules. In other words, it would be a hard fork—users who hadn’t updated their software would remain on a network incompatible with the new rules, and unupdated miners would mine “invalid” blocks. Worse, users, unknowingly, would be accepting “invalid” transactions.

New Soft-Fork Type

Nevertheless, Andresen soon found a way to mollify opponents. He discovered that OP_EVAL could be introduced by giving new definitions to a few inactive opcodes that Satoshi Nakamoto had originally included in the Bitcoin codebase as placeholders for future commands.

To everyone’s surprise, including Andresen, this also provided compatibility with nodes that had not updated to a version that would accept OP_EVAL. Such nodes would check that the hash matched the rules but would not enforce execution, instead accepting all transactions by default.

Thus, if the majority of miners accepted the new rules, the new blockchain would be accepted by all nodes — updated and non-updated alike. Such backward-compatible upgrades are known as soft forks, and Nakamoto had implemented them before, but now developers worried about the growing number of users who would need to update.

Unsettled case of soft forks: how will the next Bitcoin upgrade be activated

This also enabled work on even more reliable methods of activating soft forks. One idea was to run polls to determine whether a given feature had sufficient support among miners. For this, miners would need to include certain data in mined blocks signaling their readiness to adopt new rules. If the upgrade enjoyed majority support, it would be activated in future releases.

P2SH

But all these efforts were overshadowed by the vulnerability discovered by O’Connor. As a result, the developer community split into two camps: some considered the delay in activating OP_EVAL unwarranted, while others warned that the proposed fixes could negatively affect certain key Bitcoin properties.

A number of developers, including Luke Dashjr, Peter Velle and Gregory Maxwell, proposed for upgrades like OP_EVAL a method named Pay-to-Script Hash (P2SH). But the implementation problem remained in the form of a soft fork to prevent the network from splitting into two separate chains.

The opcodes then in use had certain limitations, and Andresen proposed a new P2SH solution. It did not require an opcode — instead, it proposed introducing code that would recognise a certain transaction format and validate it using new instructions.

Unupdated nodes would interpret this unconventional format using standard logic, confirming the correctness of the transactions. This meant P2SH could be implemented as a soft fork — if the new rules had majority backing among miners, all nodes, updated or not, would accept them.

It seemed Andresen’s proposal satisfied everyone.

«At first glance this seems acceptable to me», — wrote O’Connor.

At a developer meeting held in January 2012, it was decided to implement Andresen’s proposal. By February 1, miners were to signal their readiness to support it, and another two weeks would see a new release that would activate the soft fork.

But the world would not stay peaceful for long.

Criticism of P2SH and Alternative Proposals

Consensus was disrupted by Luke Dashjr, who, out of necessity, left the meeting early and only later learned that Andresen’s version of P2SH had been adopted as a compromise.

Luke Dashjr.

In his view, this solution complicated the protocol and carried some unclear consequences. He expressed his concerns to Andresen but could not persuade him to abandon the plan. Luke Dashjr voiced his discontent on BitcoinTalk, refusing to accept P2SH and stating that Andresen was the only one supporting the decision.

«With Gavin’s latest code, he’s trying to make everyone vote for P2SH. If you want to show you disagree with this crazy change to the protocol, you need to modify BitcoinD’s source code. Otherwise you will default to voting “for.”

The tone of his objections and the sharp accusations toward Andresen did not win broad support among developers. Some felt that, rather than focusing on the technical aspects, he had become personal.

Dashjr, meanwhile, was one of the most ideologically driven contributors. Some even believed such statements called the developer’s mental health into question. There were, however, others who preferred not to dive into technical details and simply trusted Andresen.

Luke Dashjr [a devout Christian and, at the same time, proponent of the Flat Earth theory — ForkLog] challenged not only the technical aspects of P2SH but also its philosophical implications for Bitcoin governance.

«If you want to have a monarchic currency, why not just use the Federal Reserve dollar?» — he replied to one critic, after which he was accused of seeking to usurp power.

In response, Dashjr wrote his own version of P2SH called CheckHashVerify (CHV). Essentially an alternative implementation of P2SH, adding a new opcode and not requiring the unconventional interpretation of transaction outputs.

Gavin Andresen, however, did not wish to delve into the debates.

«Luke, you’re testing my patience. I’ll step away from the code for a few days to calm down and not do something stupid», — he replied.

Among those voicing concerns was Amir Taaki. But this happened not because he opposed Andresen’s decision or fully agreed with Dashjr.

Amir Taaki. Photo: Parallel Polis.

Taaki was a little over 20 at the time, and his name was not yet widely known, but as a committed anarchist he already saw Bitcoin not merely as software but as an opportunity to resist the establishment. For much of this, he was pushed out of Bitcoin’s inner circle.

This, in turn, undermined his belief that the development process should be sped up. Taaki believed the decision-making process should be slower and involve a broader circle of users.

In his view, Andresen’s and Dashjr’s proposals differed less than they seemed, but he ultimately gave indirect support to the latter, stressing the importance of taking user opinion into account.

«I am concerned that Bitcoin could one day become corrupted. Pay extra attention to this as a chance to foster a culture of openness», — Taaki stated.

Differences between P2SH and CHV he detailed on his blog, noting the option created by hashing power-based voting.

One CPU – One Vote

During the events described, Bitcoin’s network had already diverged somewhat from the form in which Satoshi Nakamoto had presented it. In the white paper, the creator envisioned that the computing power required to sustain the Proof-of-Work algorithm would be supplied by users via their personal computers.

«In essence, Proof-of-Work is one CPU / one vote», — Nakamoto wrote.

This model assumed that any user could become a miner and participate in creating blocks, confirming transactions, and implementing developer changes to the code.

However, over time, individual miners began to matter less. This was driven by GPU-based mining, pioneered by Laszlo Hanyecz (the same man who paid 10,000 BTC for two pizzas in May 2010), and by the pool-based mining model introduced by Slush Pool’s founder Marek Palatinus. Mining ceased to be a home hobby and became the preserve of larger firms.

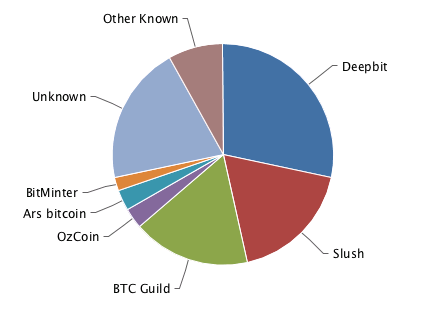

By the end of 2011, more than half of Bitcoin’s total hash rate was controlled by just three pools: DeepBit, Slush Pool and BTC Guild.

Some saw this as a threat to the network as a whole, while others called the mining centralisation a temporary inconvenience that nonetheless helped make soft-fork activation more manageable and thus less risky.

To Vote or Not to Vote

The situation was complicated by the fact that Andresen’s and Dashjr’s proposals reflected different approaches to Bitcoin governance. Up to that point, developers had spoken of upcoming upgrades as a kind of vote on a proposal. While this terminology would later become part of the lexicon, technically developers no longer asked miners for their views on new rules. Rather, it was a way to gauge whether they were ready to deploy the upgrades.

Some developers, including Gregory Maxwell, advocated restricting miners’ votes strictly to questions about transactions, and not giving them power to determine the network’s operating rules.

«What happens if the overwhelming majority of miners, perhaps even 100%, decide to keep the 50 BTC reward forever? Nothing. Miners who change this rule in their software will simply cease to exist from the network’s perspective», — wrote him.

Dashjr did not disagree with Maxwell on this, but did not see a practical way to ensure network security if developers pushed changes without miner support.

«Miners could simply refuse to confirm P2SH transactions, thereby protecting themselves from changes by developers. And if developers lack miners’ support, guess what happens? A simple 51% attack—the network will not be as secure!»

From this vantage point it is easier to understand why Dashjr believed Andresen, in pushing P2SH, was abusing his role as lead developer: if a miner used standard software to create a block, he would automatically be voting for P2SH.

In response, he created patches that would give miners the right to vote for or against P2SH and CHV. And although few used this code in practice, it did have an effect. Tycho, operator of the largest pool at the time, DeepBit, admitted that he did not feel comfortable facing the prospect of weighing two competing proposals, especially when there was no consensus among the developers themselves.

«I don’t want to be the one person who makes such a decision», — wrote him.

Stalemate

Tycho’s position made the situation even harder — without his support, representing more than 30% of the network’s hash rate, activation of P2SH looked unlikely. By late January 2012, as the first round of voting neared its end, it seemed the proposal would not reach the necessary backing.

The likely delay drove Andresen and other developers to despair.

«I think until someone sets a deadline for this process, it will never finish, because there will always be another guy with a new great idea», — Gregory Maxwell wrote in an IRC channel for developers.

Andresen accused Tycho of the stalemate. Stating that one man with enough hash power could block any changes, he called it “wrong” to use the operator of the largest mining pool to oppose the overall consensus.

Nevertheless, while Andresen urged public pressure on DeepBit and even offered to compensate losses if activation of P2SH would lead to financial losses, Tycho refused to vote for the proposal.

Arguments from Andresen found resonance among users who blamed Tycho for delaying the upgrade. Yet the DeepBit operator stood firm: he did not want to be the single person to decide the issue’s fate, noting that the combined power of other pools would be enough to back the decision.

Second Round of Voting

Failing to secure sufficient miner backing, Andresen was compelled to discuss his proposal more publicly, and at one point even allowed that CHV could become an alternative route out of the impasse.

However, there were clear disagreements between those who believed miners should decide between P2SH and CHV, and those who argued for a decision based on meritocracy. The latter included BitcoinTalk moderator Theymos.

«Blocks can be rejected by clients. If enough clients do this, miners will be unnecessary», — wrote.

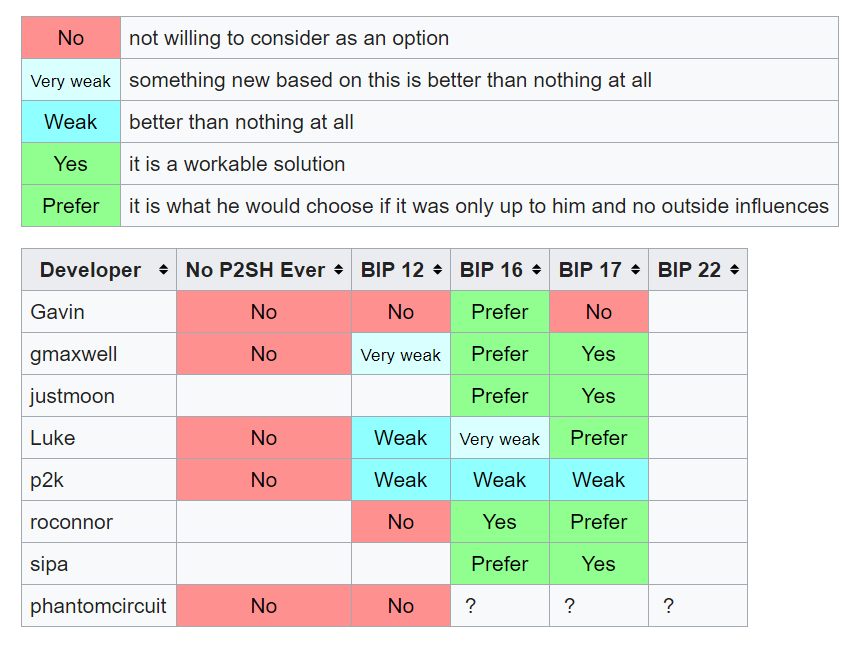

Theymos also proposed regular meetings of a small circle of experts who would gather every two weeks and vote on proposals. Perhaps by coincidence, Dashjr soon created a Wiki page where the most prominent developers could vote on proposals.

Shortly thereafter, Maxwell, Velle and others signalled that although they preferred P2SH (BIP-16), they were also prepared to back CHV (BIP-17). O’Connor and Dashjr agreed that P2SH could be adopted, but they preferred CHV.

Only Andresen categorically refused to back CHV.

But more importantly, CHV had too little support among miners. By mid-February 2012, P2SH supported about 30% of the hash rate, CHV only 2%. This forced Dashjr to reluctantly concede P2SH’s dominance and even consider withdrawing his proposal altogether.

The second round of voting was scheduled for March 1, and as that date approached, P2SH gained more support, nearing the 55% threshold. Tycho and Dashjr had no choice but to accept the majority’s choice.

Soon, Andresen announced the activation of the soft fork, and on April 1 it was successfully completed. The first protocol created after Satoshi’s departure was implemented in Bitcoin’s main network.

The arduous activation process for P2SH had a lasting influence on Bitcoin’s development structure. Andresen achieved the adoption of a solution he had created, and even if some questioned his leadership during the crisis, he ultimately cemented his status.

Meanwhile, attitudes toward Dashjr and Taaki among the community were no longer favorable. At one stage Andresen even asked Dashjr to step back completely from Bitcoin Core development, though later he either rejected this idea himself or the CHV author simply ignored his advice.

Greg Maxwell joined the ranks of key developers, gaining commit access to the project alongside Andresen, Vladimir van der Laan, and Jeff Garzik.

A broader development tone was set: a more pragmatic, technically grounded approach was welcomed, while eccentric contributors gradually lost influence. Yet ideological differences persisted and resurfaced in the years that followed.

A year later, answering a video in which Peter Todd argued against increasing block size, Andresen said:

«The block size will be increased. Your video will just make a lot of people worry about things that aren’t worth worrying about. It will be exactly the same as Luke Dashjr’s proposal last year — a storm in a teacup.»

What the decision-making process in a decentralised digital currency network should look like remains unsettled, and before a final answer is found, many years will pass.

*****

In 2016 Andresen backed the version that Craig Wright, an Australian, was the creator of Bitcoin, after which his access to updating the Bitcoin Core repository on GitHub was revoked and he left the project. In 2017 the developer supported Bitcoin Cash.

In the summer of 2020 he retracted Wright claims, saying he had been misled about the creator’s identity.

Follow ForkLog’s news on Telegram: ForkLog FEED — the full news feed, ForkLog — the most important news and polls.

Рассылки ForkLog: держите руку на пульсе биткоин-индустрии!