What is a central-bank digital currency (CBDC)?

What is a central-bank digital currency (CBDC)?

A central-bank digital currency (CBDC) is money that exists only in digital form and is a direct liability of a state’s central bank (CB).

CBDCs are, for now, the third widely recognised form of money alongside physical cash and conventional digital bank money, which are liabilities recorded on commercial-bank accounts.

Why issue a CBDC?

Central banks already create money digitally, and a large share of payments and transfers is cashless.

CBDCs differ from the existing set-up in several ways:

- A CBDC is intended to bolster stability and competition in finance amid rivalry between banks, technology firms and cryptocurrencies.

- It can improve financial inclusion by offering a lower-cost payments infrastructure. It would also make it easier for central banks to operate in an increasingly digital economy.

- A CBDC could expand the policy toolkit available to regulators—for instance, helping them avoid the “zero lower bound” trap. Thanks to programmability and transparency, CBDCs could make monetary control easier. More transparent data on payment flows would improve macroeconomic statistics.

- It can encourage the use of local currency for everyday payments, a priority in economies prone to dollarisation.

- A commercial, bank-only version of a CBDC could reduce settlement risk, provide round-the-clock access to liquidity for banks and cut the cost of cross-border transfers.

The motivation for CBDC research and development varies by jurisdiction.

In advanced economies, central banks view CBDCs as a way to enhance safety, resilience and efficiency in domestic payments and to support financial stability.

For central banks in emerging markets, financial inclusion is a key driver.

What types of CBDC exist?

There is no single accepted taxonomy, but experts at the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) have identified two main types:

- Retail CBDCs (rCBDC), intended for the general public, to provide risk-free digital means of payment for everyday transactions;

- Wholesale CBDCs (wCBDC), for use by financial intermediaries, functioning like central-bank reserves but with additional features enabled by tokenisation.

CBDCs are also classified by architecture, depending on how the central bank and private providers interact in processing transactions, recording payments and serving customers. From this perspective they fall into three models:

- Single-tier system. The central bank processes all payments, performs KYC/AML checks and provides other services. This model is deemed inefficient because it sidelines the private sector. A central bank acting as intermediary in all financial relationships could stifle innovation and market development.

- Two-tier system. Customer-facing services are provided by the private sector, while the central bank processes balances “wholesale”—aggregated bundles of retail transactions. BIS analysts consider this more efficient than a single-tier design. It reduces the need for centralised data collection and enhances data security.

Hybrid architecture is a two-tier structure with closer central-bank oversight of transactions. The private sector onboards customers and handles payments. In addition to wholesale processing, the central bank has access to retail transaction flows. This allows the regulator to step in if a payment provider fails, ensuring safety and continuity of service.

Where are CBDCs being rolled out?

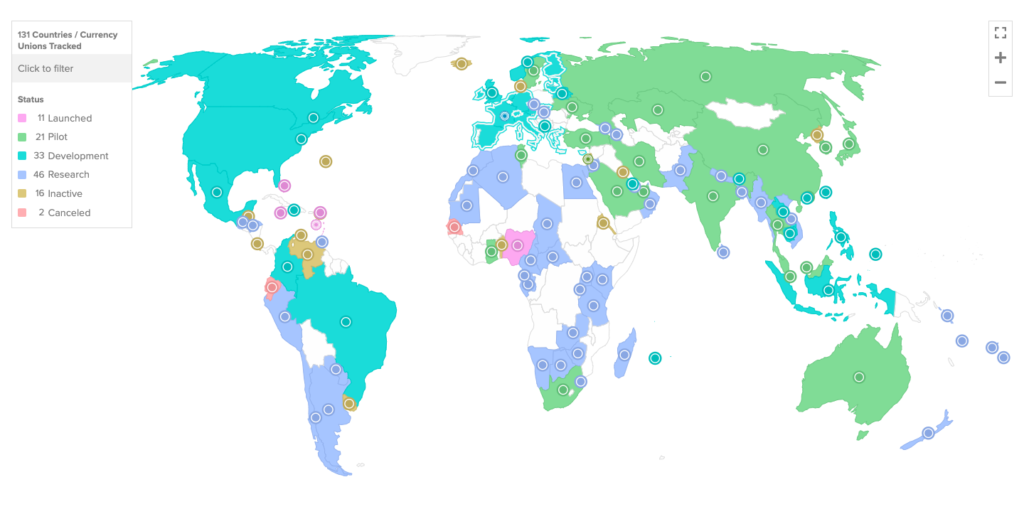

As of February 2024, more than 130 central banks—together accounting for 98% of global GDP—were exploring the creation or rollout of a CBDC.

According to the Atlantic Council—whose analysis is cited by representatives of the ECB—11 countries have already integrated a CBDC into their financial systems. The largest is Nigeria. International Monetary Fund data indicate that by mid-2023 more than 800,000 transactions had been made in the new form of money there.

Researchers note that 46 central banks are exploring possibilities for CBDCs, 33 are developing their own solutions, and a further 21 are running pilots.

The world’s largest CBDC pilot is in China. Testing has reached roughly 260 million people across more than 200 scenarios, including public transport, e-commerce and stimulus or bonus payments.

There are also pilots involving well-known crypto firms. For example, Ripple is actively participating in CBDC projects in Palau, Bhutan, Montenegro and Hong Kong. And the Kazakh unit of the Binance crypto exchange announced a BNB Smart Chain-based stablecoin backed by the digital tenge.

What are the main risks to the financial system?

Officials and economists in various countries highlight several risks in rolling out such money:

- Classic bank run. Users of conventional digital bank money may rapidly shift large sums into CBDC, triggering runs in which private banks cannot meet withdrawal demands. Such episodes occur even at large institutions in advanced economies. For example, a bank run hit Silvergate in early 2023 when investors pulled funds over solvency fears.

- Risks to lending. A CBDC could push borrowing costs up or down by altering liquidity flows in the banking system. Credit-sensitive sectors would feel the impact—for instance, manufacturers could lose access to working capital.

- Operational and technological risks. Being digital, CBDCs are exposed to cyberattacks and technical failures. Risks include inadequate performance of the underlying technology, as well as threats to the hardware and software that ensure the system’s integrity and throughput.

- A complex legal framework. CBDCs require new legislation, including privacy standards, consumer protection and anti–money-laundering rules.

Рассылки ForkLog: держите руку на пульсе биткоин-индустрии!