What is the Lindy effect—and how to use it in investing?

What is the Lindy effect?

The Lindy effect (or Lindy’s law) is the idea that a phenomenon’s expected remaining life is proportional to how long it has already existed. First observed on Broadway, productions that had lasted 100 days were typically expected to run for another 100 (if a show had run 200 days, it was forecast to run for 200 more).

The theory’s emergence is attributed to financier Albert Goldman, who in 1964 published an article in The New Republic, “Lindy’s Law.” He suggested that the length of a comedian’s successful career depends on the number and frequency of public performances.

Mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, who worked at IBM, later invoked the effect, mentioning Lindy’s law in his 1982 book The Fractal Geometry of Nature. In recent years the idea has been popularised by writer Nassim Taleb, who described Lindy’s law in his 2012 book Antifragile.

“If a book has been reprinted for forty years, I can predict that it will be reprinted for another forty years. However—and this is the key difference from perishable phenomena—if the book is still being reprinted in ten years, one can forecast that it will be reprinted half a century later. That is why things that have been around us for a long time generally do not ‘age’ like people—they ‘age’ in reverse. Every year a thing manages to survive doubles its expected lifespan,” writes Taleb.

In this form the idea has become most popular as a way to invest in ideas, products and assets.

How do investors use the Lindy effect?

In investing, the Lindy effect serves as a kind of quality mark—“time-tested.” Applying Taleb’s book intuition to corporate assets yields the following: the longer a firm has lived, the higher the odds it will survive in future.

For example, if the financial giant JPMorgan has existed for more than two centuries, the probability that it will keep operating over the next ten years is much higher than for the exchange Coinbase. Conversely, one can forecast with far more confidence the closure of Coinbase in the next ten years than the bankruptcy of JPMorgan.

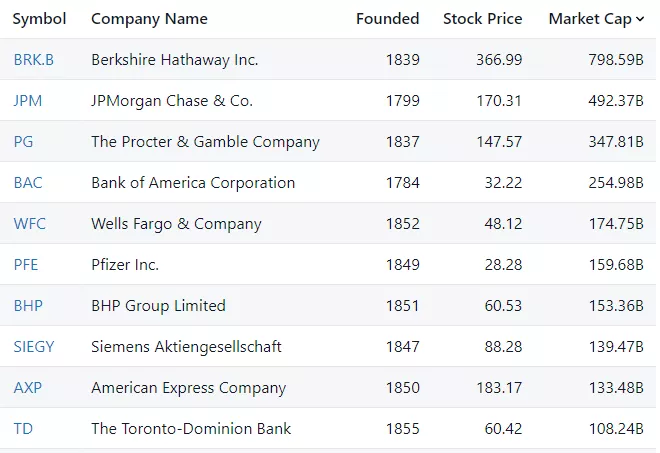

As an illustration, consider market-cap data for the ten oldest public companies.

It is reasonable to assume that older firms have deep ties at every level and superior experience in building businesses, hiring and choosing strategic directions. And while Lindy’s law does not guarantee higher returns from investing in old companies versus young ones, there is evidence of this strategy’s effectiveness over the long run.

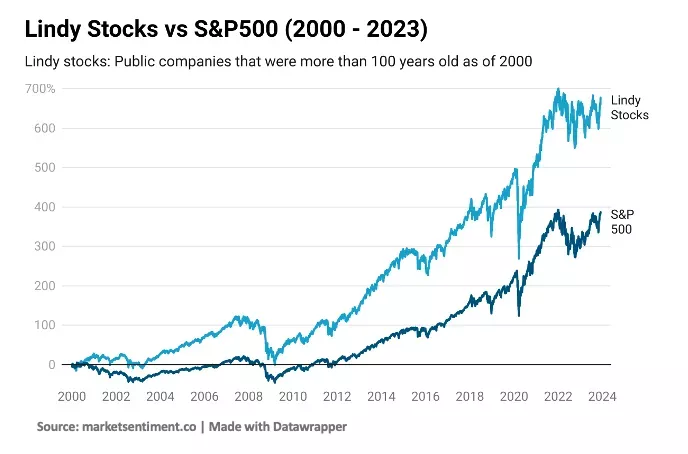

Analysts at Market Sentiment conducted a retrospective analysis of putting $100 into companies more than 100 years old, comparing it with investing the same amount in S&P 500 constituents.

They found that from 2000 to 2023 “Lindy stocks” rose 676%. Over the same period the S&P 500 returned only 386%.

Using the Lindy effect, investors forecast not only a company’s “survivability” but also technological and other trends. For example, if Web3 social networks fail to gain traction in the next five years, they are unlikely to persist into the following decade.

Applying the Lindy effect to bitcoin

Strictly under Lindy’s law, the first cryptocurrency is no different from other technological trends. Yet bitcoin has already taken root worldwide.

For instance, approval of a spot bitcoin ETF may indicate the digital gold’s full acceptance by the global financial community.

Accordingly, Lindy for BTC should be viewed through the lens of the first cryptocurrency’s steady development. If bitcoin has “survived” the past 15 years, it will likely persist for the next 15.

Applying the Lindy effect to altcoins

While bitcoin looks highly “durable,” the altcoin market does not.

Analysts often note the cyclicality to which crypto prices are subject. It is thought to correlate with the roughly four-year intervals between bitcoin halvings.

According to statistics by CoinGecko, more than 50% of all cryptocurrencies listed on its platform have ceased to exist. Since 2014, 14,039 projects have “died,” and those launched during the 2021 bull market suffered the most.

This suggests that, to apply the Lindy effect to altcoins, one should consider only those tokens that have “survived” at least two bitcoin halving cycles—around eight years.

Thus, if an altcoin has existed for, say, four years, that does not mean it will live another four. But if it has endured eight or more years, the likelihood that it will continue to trade becomes higher.

Рассылки ForkLog: держите руку на пульсе биткоин-индустрии!