You Can’t Block Them All

How autocracies are trying to stop Bitchat

A fresh wave of interest in Jack Dorsey’s Bluetooth messenger Bitchat coincided with early 2026 and an escalation of clashes between citizens and authorities in two countries — Iran and Uganda. In the former, details are hard to trace amid an information blackout; the latter offers a clearer view of digital repression and resistance.

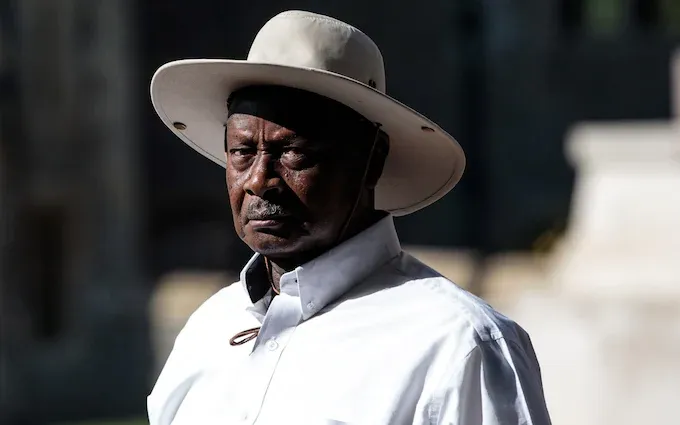

Ahead of Uganda’s presidential election on January 15th, the government of Yoweri Kaguta Museveni said it was preparing countermeasures against the decentralised radio messenger. Museveni’s challenger — singer and human-rights advocate Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, better known as Bobi Wine — urged supporters to install Bitchat to help secure a fair outcome.

In this ForkLog piece, we delve into events in the small African country and assess the technical potential of mesh networks in real-world silence.

Pre-emptive vacuum

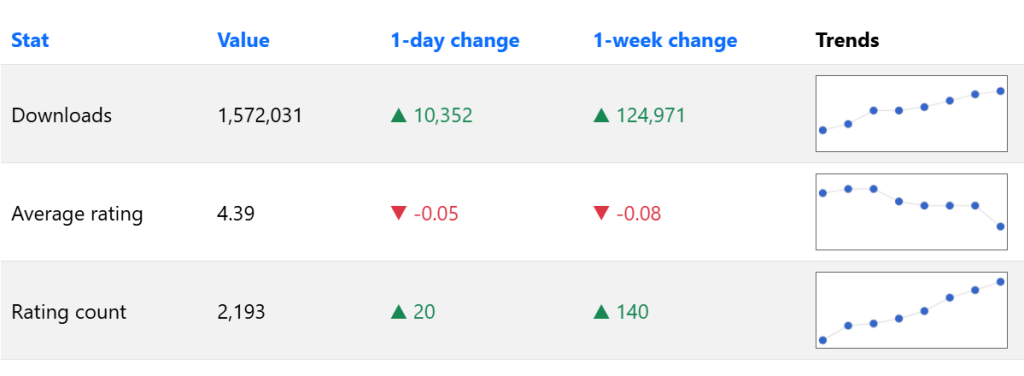

In July 2025, Twitter co-founder and Block CEO Jack Dorsey introduced Bitchat, a messenger that works via Bluetooth without an internet connection. At first, this decentralized app, coded in just a few days, only attracted tech enthusiasts. But within two months, Bitchat saw heavy use by protests in Indonesia and Nepal. By October, it became the only communication tool available after a hurricane hit Jamaica.

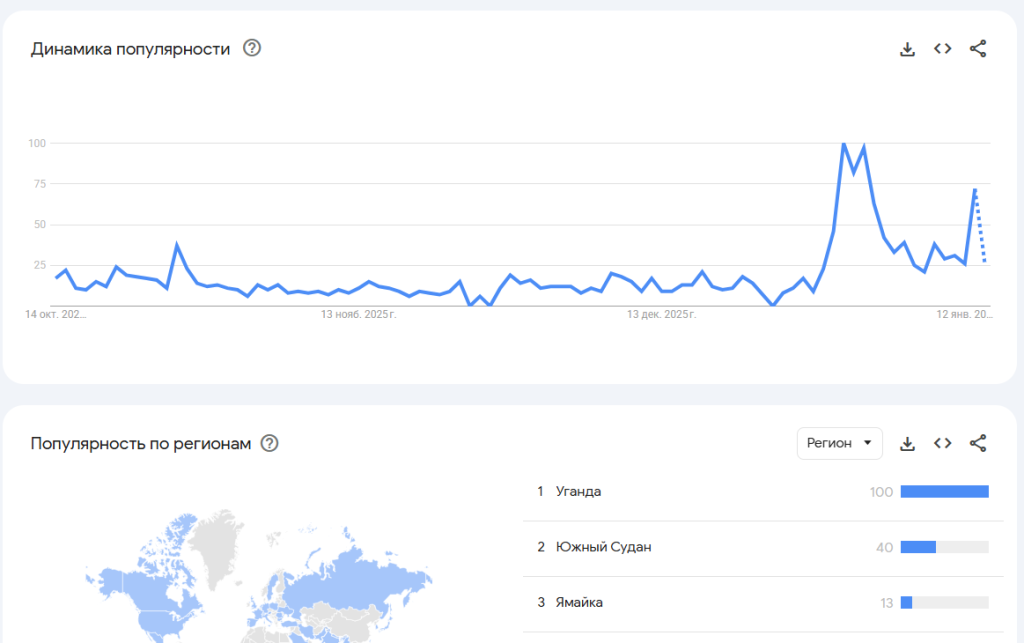

Interest in the product peaked in January 2026 during mass protests in Iran. For demonstrators, Bitchat offered a crucial alternative to counter state-imposed internet blackouts, operating independently of both government and corporate control.

Satellite internet could have been a boon for Uganda’s opposition, where authorities traditionally block communications ahead of presidential elections. However, Elon Musk is rarely quick with charity. He only opened free access to Starlink in Iran on January 13th—two weeks after mass street protests began and following a public endorsement of the protesters by US President Donald Trump. This gave civil society an additional tool to fight back, supplementing the “grassroots” Bitchat.

In Uganda, authorities prepared for a shutdown as early as late 2025. On December 19th, the Tax Authority banned the import of Starlink terminals. Access was restricted to only those with written permission from the Army Commander—who also happens to be the president’s son—General Muhoozi Kainerugaba.

Despite the import ban, many terminals previously brought in through unofficial channels remained active. This prompted authorities to pressure Musk’s company directly.

On January 1st, following a demand from Uganda’s Communications Commission, Starlink activated geolocation blocking. This rendered all equipment within the country useless.

Charismatic opposition leader Bobi Wine, opposing Museveni’s policies, developed a plan to counter communication blackouts to ensure the real voting results could be recorded.

On December 30, 2025, Wine called on his supporters to download the Bitchat app. His plan was to use the messenger to share election protocol data between observers at polling stations when the internet was down.

Wine also appealed to Musk, asking him to reconsider his company’s decision regarding Uganda and restore satellite coverage. In his post, he pointedly contrasted the billionaire’s enthusiastic reaction to the ousting of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela with his silence on the situation in Africa.

Countermeasures

Initially, the authorities firmly denied any plans to cut off communications. But on January 13th, they did exactly that. The directive came from the Uganda Communications Commission. At 6:00 PM local time, public access to fixed and mobile internet was shut down. The government also banned the sale and registration of SIM cards, blocked outgoing roaming, and restricted VPN use.

The regulator cited recommendations from the Inter-Agency Security Committee, claiming the measures were needed to combat “misinformation, electoral fraud, and incitement to violence.”

The Commission became the first government body in the world to declare its intent to decisively counter the decentralized messenger Bitchat—a move that took many by surprise. Most users discussing the issue on X did not understand how it was even technically possible to suppress a Bluetooth signal across an entire country.

Google Trends search data reflects the public’s scramble for the only remaining communication tool. The last major spike in searches occurred just before the shutdown on January 12th-13th.

One of Bitchat’s lead developers, using the pseudonym Calle, called on Ugandan programmers to join the project and help improve it.

Specialists in mesh networks and concerned citizens became more active on X. Most commentators believed the government would not find effective countermeasures.

Bitchat’s operating principles are elegantly simple, built on a foundation of mesh network research and experiments dating back 50 years.

A mesh network connects devices in a web-like structure. Each device, or node, can link directly with others nearby and also act as a relay, passing data along for users who are out of direct range. There are no central servers; encrypted messages are stored only on users’ own devices.

Here’s how it works: Smartphone A can talk directly to Smartphone B if they’re close. Smartphone B can then communicate with device C, which is too far from A. In this case, B acts as a relay, passing the message from C to A.

On January 12th, Calle released an update to harden connectivity in Uganda on top of the encrypted messenger.

On January 12th, the lead developer Calle released a key update to bolster connectivity in Uganda. The new Bitchat beta V1 firmware allows a device on a LoRa network—a long-range, low-power wireless system—to function as a standard Bitchat node. Messages from nearby app users are automatically routed through these long-range antennas.

While this offers a significant theoretical advantage, the current reality in Uganda is a major hurdle: importing the necessary LoRa hardware into the country is now nearly impossible.

Election day

As election day arrived, the people of Uganda found themselves in a state of digital isolation. In the capital, Kampala, security forces and armored vehicles were deployed across the city.

The police, who retained privileged internet access, made sure to announce the heightened security measures.

Tensions were further inflamed by a sensational statement from the head of the Electoral Commission, Simon Byabakama.

On January 14th, he reported receiving direct threats from unnamed high-ranking officials. They demanded he not declare certain candidates the winners.

Byabakama publicly stated he was “not in the business of distributing votes” and would announce the results as they were recorded at the polling stations.

This election day will be telling, not just for Ugandans but for the world. If Bobi Wine’s team’s plan succeeds, mesh networks will reach a new level of practical importance.

The main question troubling advocates of freedom and equality is: what does the government have up its sleeve, if anything?

If the officials’ threats are not a bluff, the world will witness another failure in the struggle against authoritarian control. But what methods could the security forces actually use?

Disabling a decentralized system like Bitchat is far more difficult than blocking a regular messenger, as there are no central servers to shut down at the provider level. However, there are ways to disrupt the network “on the ground.”

Here are potential technical methods for suppressing this kind of communication:

- Broadband Jamming. Electronic warfare (EW) systems can flood the entire frequency range with powerful “white noise.” This makes any Bluetooth data exchange impossible within a specific radius.

- Targeted Control Channel Jamming. Bluetooth uses three specific channels (37, 38, and 39) for device discovery and messaging. Modern EW systems can scan the airwaves and jam only these frequencies, preventing phones from “seeing” each other and forming a network.

-

“Black Hole” Attack. Agents can be deployed into crowds with specially modified devices that appear as normal Bitchat nodes. They accept messages from neighbors but do not forward them. With enough of these “dead” nodes, the network’s integrity collapses, trapping messages within small clusters.

-

Packet Flooding. An attacking device can send thousands of junk messages per second. This overloads the phone’s processor and quickly drains the battery, forcing users to turn off Bluetooth.

-

Exploiting Code Vulnerabilities. In July 2025, a critical vulnerability was found in Bitchat’s code related to packet signature handling. An attacker could send specially crafted “malformed” data, causing the app to crash on all smartphones within Bluetooth range.

-

“Poisoned” Installation Files. Security services could create fake versions of Bitchat that look identical to the original but contain hidden code. This code could block certain messages or transmit the user’s location to the authorities.

-

Triangulation and Direction Finding. Any phone with Bluetooth enabled constantly emits a radio signal. Using directional antennas and triangulation algorithms, security forces can pinpoint active mesh network nodes in a crowd with meter-level accuracy and physically detain the relay operators.

On a nationwide scale, the Ugandan government cannot simply “turn off” Bitchat. However, disrupting communication in a few key squares or around specific polling stations is likely within their capability.

A coastal station may include a base unit with GPS, powerful transceiver antennas, radar and communications to identify vessels, determine their dimensions and course, and coordinate with ships and aircraft.

***

According to the latest reports, Bobi Wine is under tight lockdown. Law enforcement and military units have surrounded his home in Magere, effectively confining him.

He held his final pre-election campaign rally on January 13th in Busiro East. Immediately after, the internet was shut down nationwide, and the opposition leader was placed under what amounts to house arrest. At that rally, Wine wore a bulletproof vest, and his signature red beret was replaced by a tactical helmet.

Shortly before these events, in an interview with The Telegraph, Wine confessed to profound physical and emotional exhaustion:

“Waking up every day knowing you’re going to see somebody [get] run over, somebody brutalised. You just don’t know who it’s going to be. It’s stressing, you know? But by the end of every day, you want to go back. Because as you cry for the losses, you’re seeing how much inspiration is manifested before your own eyes. And that makes everything worth it.”

Рассылки ForkLog: держите руку на пульсе биткоин-индустрии!