Object 734

A brief dispatch from a future you may not like.

As the community watches, breath held, the plunge in bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, ForkLog chose not to waste time and sent our correspondent, Sergey Golubenko, a little way into the future to see what comes next. He did the job. Read his report—the ending will likely surprise you.

Make America Small Again

In Albufeira, 20 minutes from home, I picked up three old 2024 ThinkPads and a dozen 100-watt power banks at a digital junk shop. The goods, flagged in my assistant app as dead scrap, had in fact been adapted to new realities. In a world of fully deployed MiCA and a failed Clarity Act, this hardware had become priceless—though the owner did not think so, happily parting me from most of my per-diem EURC.

Since 2028 every electronic device had been mandatorily fitted with a hardware “backdoor” and a built-in beacon for law enforcement.

Having secured the only currency that counted where I was going, I first flew, on assignment, to New York.

New York in 2029 was a digital fortress, where a national AI tracked my every step with soulless pedantry. Humanoid border guards were satisfied with my World ID, and getting the kit through was not much trouble, given certain media-worker privileges in my profile. In a world of total, immaculate control there were weak spots, which I exploited without remorse.

Sam Altman’s universal passport had become a sort of Schengen, but with a full migration of one’s identity into digits. Once I became legal to the system, the charms of the modern West opened up: the ability to spend, to move and to avoid patrols of ICE robots—or their living, very tired and feral biological counterparts of the past four years.

Forty minutes in a taxi passed quickly: on a frosty January morning I dozed to relaxation radio in a self-driving cab. Despite a turbulent eight-hour flight, my eyes would not close, distracted by the city’s ringing sterility and endlessly repeating, politically tinged billboards.

Here and there glowed Trump and the fight against illegal migrants, MAGA slogans, ads for neuro-implants to control animals—but most of all Marco Rubio, poised to move from governor of Cuba to president of the United States. Though voters were told this was a natural transfer of power, everyone understood: he was the only candidate the insurgents could accept without total revulsion. The secret deal was a tolerable plan to pacify a population long ready for extremes in an undeclared civil war.

The emergence of Zohran Mamdani was somewhat unsettling. I felt like an undercover intelligence operative. Despite wanting the presidency, his team never managed to amend Article II of the US Constitution. The amendment did not pass, like the more than 11,000 before it in American history.

As leader of the progressive wing in Congress, in Trump’s final year he tried to push through recognition of the right of free lands and the abolition of ICE. He did not achieve the goal, but he did manage a few strong compromises that offered some support to the anti-KYC camp. Aid packages with essential equipment and tools for communes were delivered by couriers using NFT passes.

After verifying my identity, an official discreetly granted me a pass to the “other America”: an SBT token. Officially, I received federal-level press accreditation to visit a closed reserve in Northern California, which instantly appeared in World App.

I landed at Sacramento airport, where a matte-olive Jeep Gladiator met me. With a restrained greeting, the driver asked me to confirm my identity. After checking the SBT, we climbed in.

The driver, S. by name—who in “legal” times designed the exchange architecture at Kraken—now served as a master of masking thermal signatures for the commune.

For about three hours we inched along streambeds and abandoned logging roads, leaving no tracks for patrol drones to find.

— Does Rubio promise an amnesty?

— As long as machines with thermal cameras hang in the sky, petrol and code are our guarantees, — S. chuckled nervously, eyes fixed on the forest.

The camp of those who had failed World ID was forced to craft stablecoins, since interaction with nationalised USDT, USDC, bitcoin and other federal cryptocurrencies was forbidden to such people.

When we reached “Shadow Crown”—a settlement literally grown into the crowns of giant sequoias—I first underwent the “contribution” ritual. The local treasury appraised my hardware. In exchange I received a set of local stablecoins backed by tokenised resources of this very real world.

My wallet looked like this:

- 400 EURC for the return trip;

- a bundle of SBT documents;

- 300 USDT;

- 100,000,000 PORK meme tokens;

- 50 USDSH (50 USD Shady Crown stablecoins, pegged to the US dollar, issued and backed by the private bank “Shadow Crown”);

- 2 DIESEL — each token is a can of diesel for charging gadgets via a generator in the underground store;

- 20 H2O — 20 tokens (20 litres of filtered water);

- 10 MEAL — 10 tokens for a day’s ration;

- 6 COMBICORM — an inexplicable value;

- 6 KORNEPLODY_LICHINKI_PACK — an inexplicable value.

I never did get an answer about the last two tokens. After a few vague, irritated grumbles I decided to forget them for now.

My address was replenished with what were, in effect, private monies of our time, independent of the Fed or the ECB. Their value was backed by the physical presence of a resource in a specific place. The true power of the blockchain revealed itself where the legal landscape had become scorched earth.

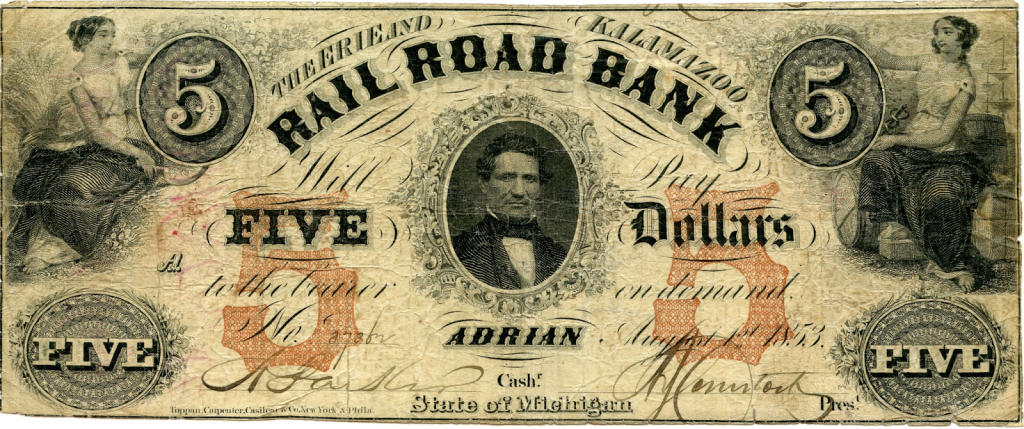

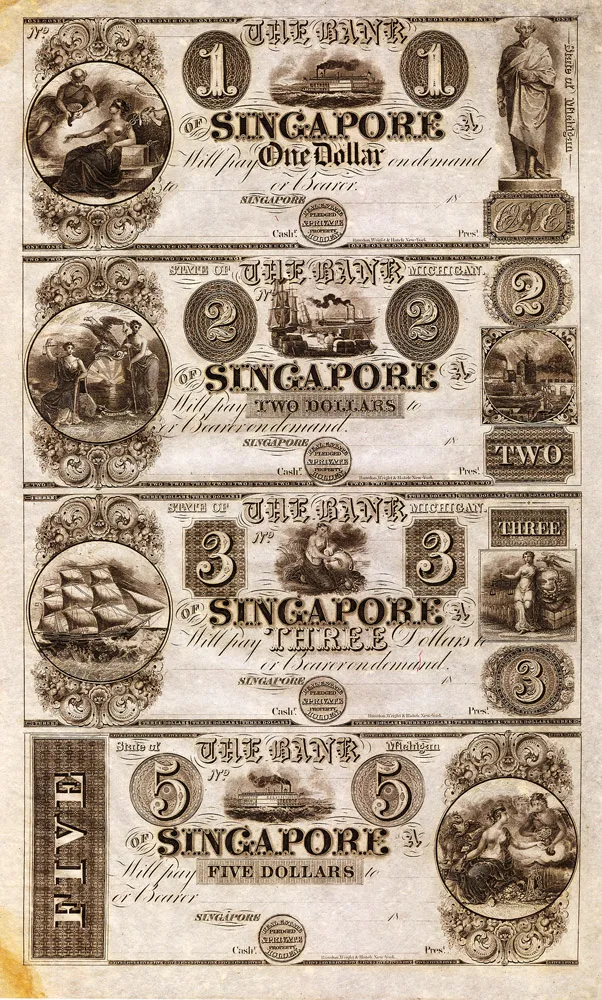

Private money of the past

Wildcat banking was perhaps the most chaotic, audacious and swashbuckling period in America’s financial history—a time when anyone with a stack of paper and a press could declare himself a banker.

It began in the 1830s. President Andrew Jackson, a fierce opponent of centralised power, destroyed the Second Bank of the United States (the Fed’s analogue of that era). He believed a monopoly on issuing money harmed ordinary people.

Control over banking shifted from the federal government to the states. Thus began the Free Banking era (1837–1863). States passed laws allowing practically anyone to open a bank by posting a small bond.

Legend has it the term “wildcat banks” arose in Michigan, where bankers opened offices so deep in the woods that their only visitors were wild cats (lynxes).

The trick? Banks issued their own paper money and, by law, were obliged to redeem notes for gold or silver on demand. To keep people from collecting the gold, they opened in the most inaccessible places. If reaching a bank meant three days on horseback through swamps, the odds of someone coming to demand gold plunged.

Bankers of that era were true illusionists. A couple of their favourite tricks:

- when an inspector set off on a check, bankers sent a wagon with a couple of barrels of gold by a shortcut so it reached the next branch before the controller. The same gold “backed” dozens of different banks;

- barrels were filled with nails and broken glass, topped with a thin layer of gold coins. The inspector peered in, saw gold and ticked the box.

Imagine a world with roughly 8,000 types of notes in circulation. Each bank printed its own money with a unique design (portraits of dogs, local heroes, mythical creatures). Shopkeepers had to leaf through fat manuals to determine whether such a bank even existed and how solvent it was. A $10 note from Chicago might fetch only $6 in New York.

This system was not only a playground for fraudsters but also highly unstable. The panics of 1837 and 1857 led to thousands of “wild” banks collapsing, leaving people with worthless scraps of paper.

The Civil War ended the madness. Lincoln needed reliable money to finance the army. In 1863 Congress passed the National Banking Act and introduced a single national currency. A 10% tax on private-bank notes made their issue pointless. Some notes from that era today fetch collectors far more than the gold once promised for them.

In 2025–2026 echoes of that era were easy to spot in the issuance of hundreds or even thousands of stablecoins. Many financial firms, shifting systems onto crypto rails, issued their own coins backed by the US dollar. You might think: there are USDT and USDC—just use them. But the difficulty of complying with still-shaky crypto rules and the then-stalled Clarity Act pushed institutions to rely on trusted brokers, who in turn had to create proprietary blockchains and stablecoins.

Some examples:

- the Fidelity Digital Dollar (FIDD) from Fidelity Digital Assets, for institutional and retail clients;

- RLUSD from Ripple;

- PayPal USD (PYUSD);

- a USD stablecoin from Exodus and MoonPay.

A conversation with the leader

Chronic shortages of power and reliable connectivity meant settlers conducted trades and synced the blockchain no more than twice a week. The rest of the time, bookkeeping was done in a simple squared notebook. During trading hours everything was digitised.

On reflection, there was little point in spending precious resources on running nodes. Instead of the hard slog of minting and transferring tokens, they might as well have stuck to a notebook and counted pebbles, dug-up tubers, roots or sequoia cones.

But, as I later learned, the higher purpose of their digital discipline was the hope of one day proving and restoring their rights; of attesting to the path they had travelled and to a life in exile before a new, loyal authority. They craved compensation and retribution, collecting digital evidence.

D.—the community’s leader—met me in one of the bunkers, essentially a shipping container buried in a mountainside, with thoughtful thermal insulation and crammed with kit. The heat-shielders had thought of everything: when the generator ran, exhaust was piped through filters into the river, leaving practically no trace. The crowns of 100-metre sequoias formed a living dome against satellites and drones. The terrain, difficult for “bloodhounds”, had been mastered in the 1960s–70s by hippies, draft-dodgers, marijuana farmers, fishermen and loggers. Only protection against thermal imagers required effort, and local specialists handled that rather well.

On his desk lay a dog-eared copy of The Network State by Balaji Srinivasan. For him the settlement was not a refugee camp but a “node” of a future state.

D. hugged me on greeting and, for some reason, scratched my back. By some inner custom, everyone else did the same.

— In Asia this already works, — he said, pointing to a map of Indonesia and Thailand’s “digital jurisdictions”. — We are building the same here. We are a cloud community that materialised in the forest.

But Shadow Crown is a peaceful enclave. To the north, in Oregon, the Obsidian Front issues tokens backed by 7.62 calibre rounds. In Nevada, the Dusty Riders live in mines, treating any newcomer with a gadget as a biological threat. We sit at the centre of a fragile ecosystem, where trust between network nodes is the only resource that cannot be tokenised.

The awakening of Object 734

My fingers froze above the keyboard, my head still pulsing with thoughts of the great future of network states and the triumph of RWA tokens over the Fed’s despotism. “The world will shudder,” I thought, pressing “Send” in the CMS.

But the button did not press. It began to melt, spreading across the screen in a neon blot.

At that moment the reality of Shadow Crown popped like a cheap VR headset. The smell of ancient sequoias and cold fog instantly gave way to the acrid, sterile reek of ammonia and stale biochemistry. The wind in the crowns turned into the metronomic, maddening beep of a cardiac monitor.

I tried to lift a hand to rub my eyes, but my hands would not obey. Instead there was a cottony heaviness in limbs that felt too short.

I lay on my back, staring at a dazzling white ceiling of cold polycarbonate. In my head, instead of Balaji Srinivasan’s quotes, the dry voice of a lab technician echoed at the edge of consciousness: “Ketamine levels normal. Object 734 is regaining consciousness.”

A sharp, pulling pain hit my abdomen. Lowering my gaze—as far as the numb body allowed—I saw not a reporter’s worn jacket but pink skin with sparse bristles. Across the middle of the belly ran a fresh, perfectly straight surgical seam, pinched by gleaming staples. On a nearby stand hung a transparent bag, slowly filling with a dark, viscous liquid. Its label read: “Bio-Asset. Neuralink Animal Project. Batch #9”.

Рассылки ForkLog: держите руку на пульсе биткоин-индустрии!