‘We’re Sorry, Carol’ – The Story Behind a Crypto Wallet in a Smart Fridge

How crypto wallets for gadgets and a machine economy curb corporate overreach.

The story of a fridge that landed its owner in a psychiatric ward reads like Black Mirror, but it is the reality of 2025. An advertising algorithm, which happened to match the owner’s name, triggered a severe psychotic episode.

ForkLog examined the incident, the public reaction, and how the “economy of things” and crypto wallets could shield mental health from corporate overreach.

“Someone is trying to contact me through the fridge”

Details emerged via a post by the victim’s brother on Reddit. His sister Carol, diagnosed with schizophrenia, had been in stable remission for over two years and led an ordinary life. That changed when she phoned him in a panic, insisting that “someone is trying to contact me through the fridge”.

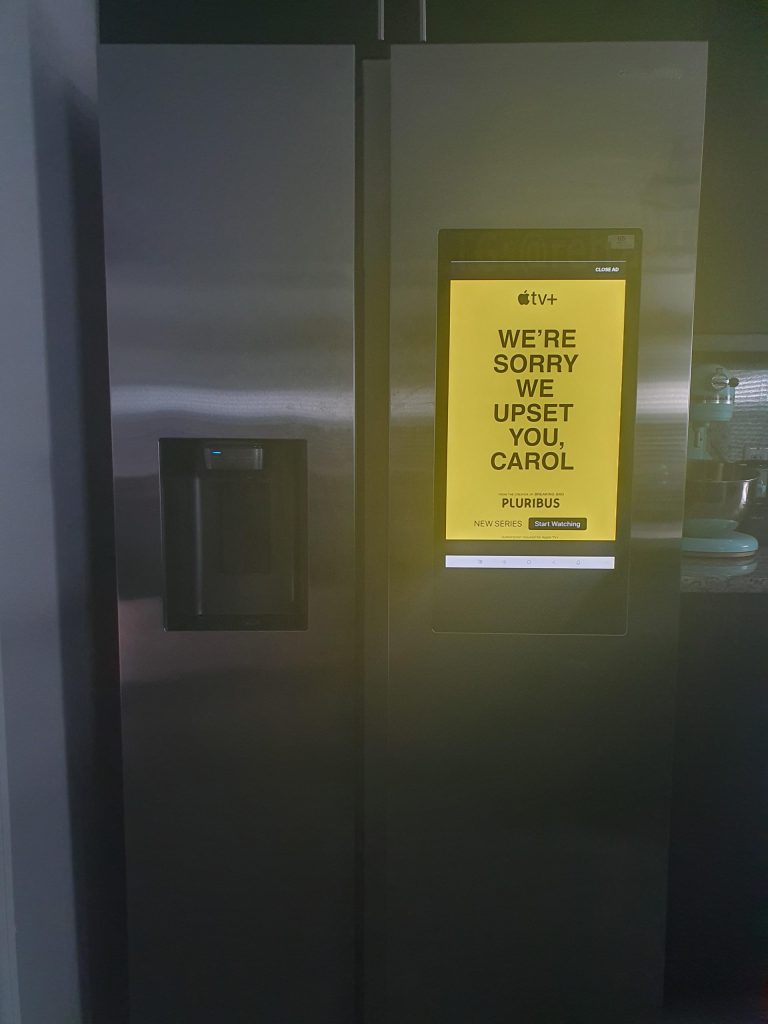

The trigger was her own premium Samsung fridge (models retail for $3,000 to $5,000). The device, equipped with a large screen, began showing an advert for the series “One of Many”. The banner displayed, in large type:

“We are sorry that we upset you, Carol.”

The coincidence of the show’s character name with that of the fridge’s owner proved disastrous. She took the text as a personalised message from an unseen watcher. That set off acute psychosis and a panic attack, followed by hospitalisation.

This was not a technical glitch but a predictable outcome of the Web2 business model. Even after paying thousands of dollars for the hardware, a user does not truly own it. The kitchen screen remains a corporate asset—a conduit for advertising and data collection. In this set-up, the user is not the customer but the resource.

The case raises knotty legal and ethical questions. Digital-law specialists note that such banners skirt the edges of legality. Britain’s Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) requires that advertising does not mimic personal messages.

On the LegalAdviceUK subreddit, users stressed that when a commercial message appears on a household appliance and masquerades as a personal address, it misleads consumers and can cause harm.

Owners of premium Samsung devices are increasingly disgruntled that their kit is turning into billboards. Many contemplate a drastic step—disconnecting “smart” fridges and TVs from the internet altogether, at the cost of built-in functionality.

The problem: users do not own their things

The internet of things is built on centralisation. Buyers of pricey gadgets expect control and get marketing instead. Smart speakers, TVs and thermostats constantly call home to the manufacturer’s servers. That creates two fundamental vulnerabilities:

- Censorship and intrusive content. The corporation decides what the user sees on the device’s screen. Disabling adverts is often impossible or requires convoluted reflashing that voids the warranty.

- Privacy leakage. Devices collect behavioural patterns. In Carol’s case, the system did not know her diagnosis; in future, integrations with medical data and AI could make targeting even more aggressive—and frightening.

The remedy lies not in interface settings but in changing the economic model of human–machine interaction.

The Web3 answer: the economy of machines

An alternative is the M2M concept. In this model, devices are no longer passive terminals. They become autonomous economic agents capable of transacting.

To make that work, a fridge or a car needs its own wallet and account. The traditional banking system is helpless here: no bank will open an account for a toaster because of KYC requirements. Blockchains do not require passports, enabling addresses for any digital or physical entity.

How it works in practice

Imagine a Web3 fridge. Instead of a permanent connection to an ad server, the device runs on an open protocol.

- Micropayments instead of advertising. The owner deposits a small balance in stablecoins or bitcoin (via Lightning Network) to the device’s wallet. The fridge automatically pays tiny sums (fractions of a cent) for weather, recipes or firmware updates directly from data providers. That cuts out advertising networks. The customer pays for a clean interface and the absence of spam.

- Sovereign identity (SSI). The device uses a decentralised identifier (DID) and proves access rights without revealing the owner’s identity (the zero-knowledge proof principle). Advertisers cannot technically target content at “Carol”, because to the network it is just an anonymous 0x… address.

The technology stack for sovereign devices

The industry is already building the tooling. The DePIN sector is one of 2025’s big trends:

- Peaq and IoTeX. Blockchain platforms tailored for IoT. They allow devices to receive unique on-chain IDs (Machine ID), turning them into full-fledged assets (Machine RWAs);

- account abstraction (ERC-4337). The standard lets builders programme wallet logic. A fridge, for instance, could have a $5 monthly cap for ad-free subscriptions. If the cap is reached, it will not show a banner; it will notify the owner to top up;

- AI agents (Fetch.ai, Ocean Protocol). A local AI on the device analyses inbound traffic. It acts as a filter (bouncer), blocking any content that could harm the user based on safety rules rather than the manufacturer’s commercial interests.

A wallet as a safeguard for the mind

Carol’s ordeal shows that “free” content or subsidised services in premium hardware carry a steep hidden price—mental health.

In the internet of things, cryptocurrencies cease to be a speculative play. They become a technical guarantor of property rights. If a device has its own wallet, it works for whoever funds that wallet.

Shifting to a model in which appliances pay for themselves (or earn by selling anonymised data at the owner’s discretion) is the only way to avoid a future in which the toaster holds its user to ransom for watching an advert.

Рассылки ForkLog: держите руку на пульсе биткоин-индустрии!