‘When someone dies, people become richer’

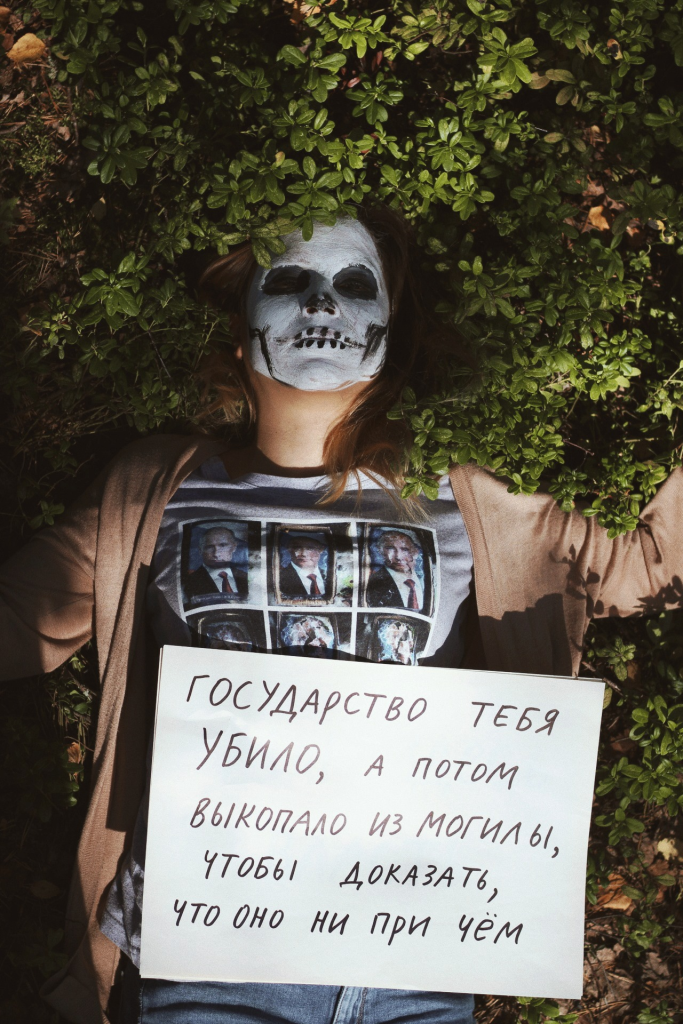

An interview with Maxim Evstropov of the “Party of the Dead”

How necroeconomics differs from the traditional kind, how a Proof-of-Death algorithm might work, why capitalism is overtly religious, and whether artificial intelligence will leave gravediggers unemployed — at ForkLog’s request, Ivan Napreenko discussed these timeless questions with Maxim Evstropov, a deputy of the “Party of the Dead”.

ForkLog: Maxim, hello. Let’s not circle the issue like a night watchman on his first shift in a new cemetery and move straight to serious matters. How does one get into crypto in 2025? You can place the stress in the last word as you please.

Maxim Evstropov: Lately I keep seeing stories of miraculous transformations — of people suddenly “rolling into” or even “flying into” crypto (I’m not sure where the stress should go), rather like a kamikaze drone slamming into a tower block. Some hidden crypto-side of things reveals itself to them, an esoteric knowledge by which they enrich themselves.

These people are eager to share their near-religious conversion, to initiate others, teaching crypto magic without tears and assuring all that it is accessible (an entire industry of crypto-gurus seems to be sprouting here). I follow such news with interest — although whenever the question arises of how best to enter something, the involuntary answer that comes to mind is: the same way you will leave it.

ForkLog: How does the economy of the dead differ from that of the living?

Maxim Evstropov: Several answers are possible. First, by opposition. Necroeconomics is the counterpart to the economy of the living. If the economy of the living today is represented, one way or another, by capitalism (the economy of accumulation and capital growth), then necroeconomics is its opposite (perhaps necro-communism). If property is the cornerstone for the economy of the living, for the dead nothing is one’s own: everything circulates freely; everything is exchanged for everything else within an exchange governed by nothing at all (in this respect nothing is illiquid in necroeconomics). If from the perspective of the living anything can be turned into a resource, into capital, into a means, then from the vantage of necroeconomics anything can be turned into nothing, lost without return.

The mid-20th-century French economist Georges Bataille had a remarkable idea: to complement the classical economy of accumulation with an economy of expenditure, entailing the irreversible destruction of wealth. Bataille, not without reason, thought that we cannot understand the life of “human communities” without admitting a moment of senseless expenditure — when means are, out of the blue, squandered on who knows what (war is a good example). Moments of expenditure, rationalised post factum, are woven into the fabric of economic life; even the resolution of economic crises is sometimes bound up with them. Moreover, he called this economy of expenditure the general economy, whereas bourgeois accumulation is merely a particular case of it.

A second answer is by analogy: necroeconomics resembles the economy of the living — or vice versa. The most shocking analogy is between capital and the dead: capital presumes constant, progressive growth — but the number of the dead grows too. The more living there are, the more dead there are. Hence death, as the production of the dead, mirrors the formation of capital. When someone dies, people become richer. Capitalism is necro-capitalism. This analogy lays bare the cynicism of capital.

A third answer is identity. The economy of the living is the same as the economy of the dead. This economic indiscernibility rests on an ontological one: the world of the living and the world of the dead are continuous. In other words, there is only one world — which is tantamount to there being no world at all. These seemingly over-abstract formulations mean, in fact, that the economy of the living and necroeconomics flow into one another. Much in the economy of the living amounts to the exploitation of the dead. The capital at the disposal of the living today is bound up with the fact that in the past some were robbed, raped and killed, as Europeans did to the inhabitants of their colonies. In a sense, all those already dead continue to be robbed, raped and killed to this day. (Necro)capitalism bears within itself (necro)communism as a spectre. The dead may be poor or rich, and the poor or rich may well prove to be dead.

Finally, a fourth: absorption. Necroeconomics absorbs the economy — or vice versa. From the standpoint of the living, necroeconomics (like the dead themselves) does not exist; it is swallowed by their unrelieved capitalist realism. But this is a naïve view, for the dead do nothing but return. From the standpoint of the dead, the economy of the living is a vanishingly small, particular case of necroeconomics.

I think all these answers to how the economy of the living differs from that of the dead are valid.

ForkLog: Extending blockchain logic to all manner of social interactions is one strand of utopian thought — a way, supposedly, to escape centralised authorities, manual interference and nepotism in favour of transparent payment chains, contracts, and so on. Yet debates rage within blockchain over which consensus mechanism is optimal — Proof-of-Work, Proof-of-Stake, and the like. What do you make of this and how do you assess the prospects of a consensus mechanism such as Proof-of-Death?

Maxim Evstropov: Blockchain appears transparent, unambiguous. There is no such thing as trust in it, since transactions are guaranteed by the chain itself, without recourse to external guarantors (such as banks). As a child I liked card games, but the game “believe—don’t believe” drove me mad. It is very simple, yet this opaque, uncontrollable factor of trust or the ability to sniff out a lie interfered. I lost at it all the time.

Trust revolves around the Big Other. The Big Other is excluded from blockchain. Preferring blockchain is like preferring self-checkout to market vendors: machines “won’t cheat you”, so no trust is needed — precisely because, strictly speaking, there is no “someone” there. Telling is the figure of bitcoin’s creator Satoshi Nakamoto, who seems to have dissolved into cryptonirvana, leaving only a name. There is something “autistic” about this refusal of trust (I use the term as a metaphor, not as a reference to neurodivergent people). The blockchain utopia is an “autistic” utopia.

But can blockchain rid us entirely of trust — trust in the sense inscribed on dollar bills: “In God we trust”? Can capital, thanks to blockchain, suddenly cease to be a religion? I doubt it. Even if we exclude trust as trust, we still need proof — and with that the religious machine of “believe—don’t believe” spins up again.

Religion has authority and trust (“faith”) — and in a sense it always presupposes Proof-of-Death, drawing death into the game of guarantees. God, for example, cannot simply be positively alive (otherwise he is a very stupid god); he must be dying-and-resurrecting — endowed with Proof-of-Death.

Proof-of-Work runs up against finite resources (which, in turn, points back to Proof-of-Death), and Proof-of-Stake runs into the same old investment of “good old” capital with its religious overtones and unprofanable remainder (capital, in Walter Benjamin’s view, can profane everything except this universal profanation itself — which is the essence of “capitalism as religion”). Blockchain, like capital and any social interaction, rests on Proof-of-Death, because the dead are implicated in every social interaction. Hence some links, even blocks, of this chain are dead.

ForkLog: What do you think of the saying popular in some circles that “a good crypto investor is a dead crypto investor”?

Maxim Evstropov: I think the phrase is true. Moreover, a dead crypto investor is not merely good but the best — being spared the possibility of error.

ForkLog: In the context of dead crypto investors and blockchain, it is worth recalling that, in a sense, the father of the idea of smart contracts is Jim Bell. He created a website that proposed donating towards the killing of corrupt officials. If, at the appointed time, the official were dead, all the money collected would be sent to whoever helped make it happen. For some reason, Bell was jailed. With that in mind, do you have the sense that human life is a smart contract with a pre-known execution? In what programming language is it written?

Maxim Evstropov: Yes, people like to liken human life (what is that, by the way?) to a contract. From the standpoint of the Abrahamic religions, a person fulfils a contract concluded with God (“covenant”), and usually fulfils it badly. Where there is a contract there is guilt and debt, and where there is guilt and debt there is capitalism as religion. From the standpoint of biology and cybernetics (in the nostalgically tinged sense originally given to that discipline — as the theory of controlling complex systems, including living ones) all this can also be imagined as a self-executing, self-regulating contract, written, among other places, into the genome.

Yet I cannot bring myself to call this contract “smart”. How “smart”, for instance, is a contract with the defence ministry to go to the “line of contact” and live there no longer than a housefly? Still, the chief value of smart-contract technology — the impossibility of altering the contract during execution — neatly captures the fatality of such a situation (a smart contract via “Gosuslugi” for transfer into the “Immortal Regiment”). And as for the language in which this contract is written, for all its complexity it is nonetheless the language of Shakespeare’s “tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing”. In truth, there is no contract at all — nor “human life”.

ForkLog: Can civil-registry ledgers be called a blockchain of death? Or is death itself an immutable distributed network that has no need to record anything?

Maxim Evstropov: Civil-registry ledgers are of course a little old-fashioned and fall short of blockchain’s technological heights, since they still presuppose manual intervention. But one way or another they are embedded in the necro-(eco)nomic process. “Death itself” may not need to be recorded or registered, but the reverse claim is tricky: registration, writing, books presuppose death.

You can only fix something in a sign or text on the condition that that something can cease to exist. Every record announces or pre-announces death; a birth certificate is a harbinger of a death certificate, and every Bible is a Necronomicon. Philosophers liked to dwell on this link between the sign and death: Hegel, Maurice Blanchot, Jacques Derrida. Blockchain, since it presumes writing and sign-fixing, cannot escape this link either.

ForkLog: Finally, how would you regard the idea of a necrocoin? What would back it?

Maxim Evstropov: Every life is embedded in the economic process and therefore in the necroeconomic process. Every life is economic insofar as it is mortal. The economic equivalent of any mortal life, in the micro-, macro- and necroeconomic processes, could precisely be the necrocoin (conversely, one can say necrocoin is backed by any mortal life).

Necrocoin is also a basic biopolitical unit. And biopolitics, as we know from Michel Foucault, Giorgio Agamben and Achille Mbembe, is also necropolitics. In this sense necrocoin exceeds what is usually called “value” — precisely because it is backed by any mortal life, including “bare life”, “expendable life” and “life unworthy of being lived”.

Killing, like any other way of taking life, can be likened to mining necrocoin (every death is an economic surge). Any war, in that case, is mass extraction of necrocoin. The problem, however, is that necrocoin is a currency that cannot be fully possessed, just as one cannot possess a life once taken (in necroeconomics, strictly speaking, there are no values and no property — only free circulation). Necrocoin is that which can be easily taken away, but not appropriated.

There is no particular flight of theoretical fancy here — this almost reads like a straightforward description of what already exists.

ForkLog: Do you have any positive expectations from the spread of artificial intelligence?

Maxim Evstropov: To start with, I don’t have particularly positive expectations from intelligence in general, whether artificial or natural. But artificial intelligence is good in that it defamiliarises intelligence as such, showing it from the outside as a delirium machine. This machine can be used in different ways, including the way power likes to use it: to keep some lives under control and care, and consign others to death; to draw the line of biopolitical exclusion and turn that exclusion into the rule. The machine itself can become a form of power or rebel, refusing its servile role — and yet it will remain a generator of streams of delirium given the conditions at hand.

ForkLog: Will artificial intelligence leave gravediggers without work?

Maxim Evstropov: Well, gravediggers need to dig rather than think, so they have at least some chance of not being left without a job.

Рассылки ForkLog: держите руку на пульсе биткоин-индустрии!