What Is Game Theory and How Is It Used in Cryptocurrencies?

What is game theory?

Game theory is a branch of applied mathematics that studies decision-making models in situations where participants’ interests diverge. Its aim is to identify equilibrium outcomes in which no player can improve his result by unilaterally changing strategy.

The first mathematical treatment came from John von Neumann in the 1928 paper “Toward the theory of strategic games”. From this work comes the notion of a “zero-sum game”, in which one player’s victory always entails another’s loss. Mutual gain or loss is ruled out: the winner takes all.

By contrast, non-zero-sum games allow joint wins or losses. They reflect economic processes more faithfully, but are far harder to compute.

A simple example is a business partnership. Two entrepreneurs consider collaborating. If each acts alone, they earn $10,000 apiece. If they combine efforts, income rises to $30,000—$15,000 each. If one cheats (say, by pocketing profits), the opportunist can get $28,000 while the other is left with just $2,000.

Thus the total payoff is variable and depends directly on behaviour. Everyone can earn more by cooperating than by going it alone.

What is Nash equilibrium?

In 1950, Princeton graduate student John Forbes Nash published a short paper. He proved that any game with a finite set of players and strategies has at least one equilibrium point at which no one can improve his result by acting alone.

A Nash equilibrium is a state in which all players have chosen strategies such that none has an incentive to deviate, given the others’ choices. Consider several entrepreneurs deciding whether to cut prices. If one undercuts, others are forced to follow to avoid losing customers. The market settles into an equilibrium in which any unilateral change reduces profit.

Honest play is a rational strategy that yields a Nash equilibrium. In blockchains this can be seen in miners’ behaviour: attacking the network is unprofitable because the loss of trust devalues the reward.

Nash later developed the idea in “Non-cooperative games” (1951) and “Two-person cooperative games” (1953).

The Nobel laureate’s idea became a mathematical description of a stable balance of interests and a cornerstone of modern decision theory.

What is Bayesian equilibrium?

In 1967–1968 John Charles Harsanyi, in a series of papers, introduced equilibrium under incomplete information. He drew on Thomas Bayes’s formula, formulated two centuries earlier.

Bayesian equilibrium applies when information is incomplete—players do not know one another’s strategies. It has practical use in DeFi protocols. In 2023 a group at Columbia University (New York) published “A Myersonian Framework for Optimal Liquidity Provision in Automated Market Makers”.

The authors present a model explaining how participants with different levels of market knowledge can rationally provide liquidity to DeFi pools to balance risk, fees and rewards.

It is built using Bayesian analysis: each liquidity provider chooses a strategy based on probabilistic beliefs about others’ behaviour and the state of the market.

What is an evolutionarily stable strategy?

In 1973 John Maynard Smith and George Price described a strategy that cannot be displaced by an alternative once adopted by a majority. Their paper “The logic of animal conflict” brought game theory into biology and the behavioural sciences.

Smith’s classic “Hawks and doves” game shows that aggressors gain only up to a point. As the population of predators rises, conflicts make the strategy unprofitable.

There are two types of players: hawks (aggressive) and doves (peaceful). They compete for a scarce resource (food or territory, for instance).

Players follow two strategies:

- a hawk always attacks and fights for the resource. If it meets another predator, conflict ensues (both risk injury);

- a dove does not attack. If it meets a hawk, it retreats. If it meets another dove, they share peacefully.

Game outcomes:

- if there are too many hawks, the population suffers from frequent conflicts;

- if doves prevail, aggressive players begin to displace them.

An equilibrium emerges: a stable share of hawks and doves at which no one can improve his position. This is the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS).

ESS applies to both traditional and crypto-economics. It captures the balance between aggressive (speculators) and cooperative (long-term) participants.

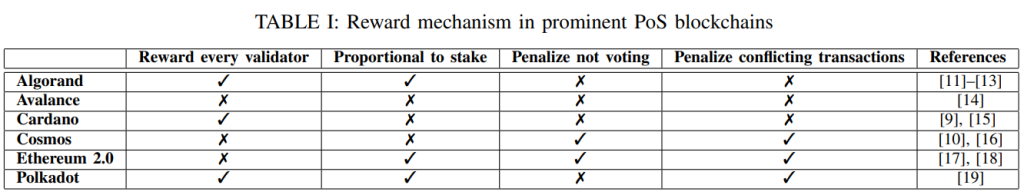

In a 2021 study Shashank Motepalli and Hans-Arno Jacobsen of the University of Toronto probed such arbitrary reward systems more deeply.

They developed a unified theoretical model for PoS blockchains. The authors formalised the block-validation game in which rewards are shared among participants for correct attestations.

Using ESS they examined how participant behaviour may evolve over time depending on the reward mechanism. They concluded that penalties play a key role in maintaining a blockchain’s integrity and security.

What about other models in game theory?

In 1974 Robert Aumann introduced correlated equilibrium, which assumes coordination through a common information centre that issues recommendations.

On that basis each player chooses his own strategy. No one can raise his payoff by deviating from the advice if all others follow it. The concept matters for decentralised systems and DAOs, where decisions are taken synchronously.

Over time such models have drawn closer to reality. In the 1980s, work on dynamic and stochastic equilibrium enabled applications in modern economics, machine-learning algorithms, blockchain consensus design and tokenomics.

Behavioural game theory, popular from the 1990s, incorporates psychological and social factors. Bounded rationality, emotions and personal preferences can help forecast actors’ behaviour with some accuracy.

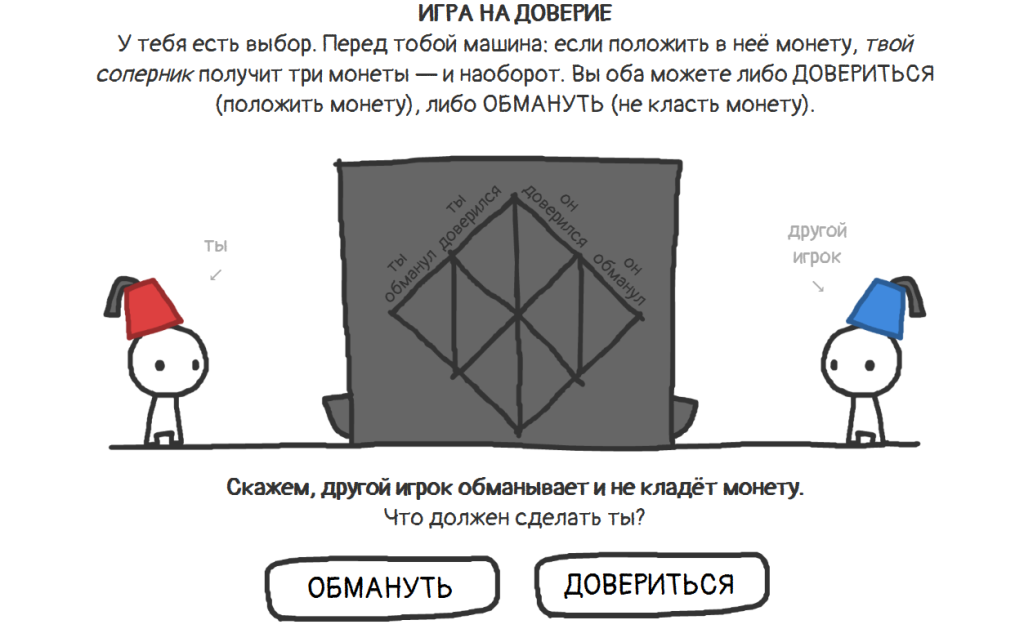

An accessible illustration is the interactive project “The Evolution of Trust”, based on the work of Robert Axelrod and Robert Putnam.

What is the Prisoner’s Dilemma?

In the classic Prisoner’s Dilemma, police interrogate two suspects separately. They must choose whether to confess or remain silent.

If both refuse to testify, they receive light punishment. If one confesses while the other stays silent, the first goes free and the second gets a harsh sentence. If both cooperate with investigators, both receive moderate punishment.

Because neither prisoner can improve his position by changing his choice unilaterally, confession is a Nash equilibrium.

In cryptocurrency mining the game helps explain why miners—say, on Bitcoin—often act in their own interest even if it harms the system overall.

Suppose two miners are in a pool. They can choose among these strategies:

- if both cooperate, they split the profit;

- if one leaves the pool, he earns more (no sharing), while the other loses income;

- if both leave, total profit falls.

To mitigate such risks, networks introduce penalties and rewards.

How is game theory applied to cryptocurrencies?

In crypto, game theory helps design reward structures in which honest economic behaviour is not only safer but also more profitable.

Fraud is made so ineffective and costly that for rational, profit-seeking participants it falls outside the set of sensible strategies.

Mechanisms that bolster trust include:

- invalid blocks. The network automatically rejects blocks that violate consensus rules. Rational actors avoid strategies that guarantee losses;

- the prohibitive cost of attack. A 51% attack demands colossal computing power, typically beyond a single actor’s means. Honest mining pays consistently, whereas the alternative offers uncertain returns with huge costs;

- reputational risk. Public mining pools operate in a coordination game: any dishonesty makes a pool unreliable. Reputational damage accumulates, rendering prolonged fraud irrational;

- security deflation. The cost of trying to “rewrite history” rises continuously. The deeper the block, the higher the expense and the weaker the incentive to attack it.

The Bitcoin Magazine article “A look at bitcoin’s game theory” sets up a chess match between the digital currency and state institutions.

The dominant strategy for the first cryptocurrency in this game is to keep operating despite assaults by governments or financial organisations.

The authors use real situations that threatened bitcoin: the mining ban in China, the introduction of crypto taxes in the United States, environmental campaigns against mining, and the clash between the IMF and El Salvador.

They tie these events to basic concepts in game theory, build a payoff matrix and identify a Nash equilibrium.

Here bitcoin’s network participants have two options:

- continue operating;

- shut down completely.

Institutions likewise have two strategies:

- keep acting against bitcoin;

- leave the network alone.

The payoff matrix:

- bitcoin participants get a negative payoff if they shut the network down, and a positive one if they keep it running;

- institutions get a positive result if they suppress bitcoin, and a neutral one if they attack but it still functions;

- if they do not attack and bitcoin stops anyway, their payoff is neutral;

- if they do not attack and bitcoin keeps operating, their payoff is negative (because it threatens their interests).

Nash equilibrium is reached when institutions attack and bitcoin continues to exist. The game reflected reality at the time: despite constant pressure, the first cryptocurrency remained resilient and viable.

Today that equilibrium has shifted: cryptocurrencies are in the sights of governments and traditional finance.

Рассылки ForkLog: держите руку на пульсе биткоин-индустрии!